![]()

1

Shock

Marius Terblanche1 and Nicole Assmann2

1Guy’s & St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK

2Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

Take home messages

- Human survival is absolutely dependent on oxygen for respiration, the process by which cells derive energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

- Mitochondrial respiration is compromised by a reduction in oxygen delivery due to circulatory failure (e.g. hypovolaemic shock) and/or an inability to appropriately utilise delivered oxygen (e.g. during sepsis).

- Circulatory failure of any cause activates a systemic immune/inflammatory response.

- Inflammatory signalling and gene expression of inflammatory mediators starts a cascade of downstream effects often culminating in organ dysfunction or failure.

1.1 Introduction

Oxygen is the most supply-limited metabolic substrate. Under normal physiological conditions oxygen (O2) supply is closely matched to mitochondrial consumption. Shock is caused by an imbalance between the supply and demand of oxygen. Depending on the aetiology, either the delivery of oxygen and other metabolic substrate is reduced or increased metabolic requirements are unmet despite increased delivery. The inability of peripheral tissues to utilise substrate may contribute to this imbalance.

A number of different conditions can cause shock (Table 1.1). The original Hinshaw and Cox classification differentiated between four main categories [1]. More recently, endocrine shock, caused by thyroid disease or adrenal insufficiency, was recognised as another aetiological category but will not be discussed here [2].

Table 1.1 Classification of Shock

| Hypovolaemic | Loss of circulating volume |

| Cardiogenic | Myocardial or endocardial disease |

| Obstructive | Mechanical extra-cardiac obstruction of blood flow |

| Distributive | Vasodilatation and altered distribution of blood flow |

| Endocrine | Thyroid disease, adrenal insufficiency |

To unravel the often complex clinical scenarios associated with shock, we find it useful to start by differentiating between low versus high cardiac output states. We therefore divide this overview of shock into three parts:

- low cardiac output states,

- high output states, and

- the pathway to multi-organ failure.

1.2 Low output states

Low cardiac output and systemic hypoperfusion leads to oxygen supply failure. This situation is exacerbated by anaemia in haemorrhagic shock – oxygen delivery (DO2I) is determined by the cardiac output (CO) and blood O2 content (CaO2), with the latter predominantly a function of haemoglobin concentration and arterial oxygen saturations.

DO2I = CO × CaO2

CO = [HR × SV]

CaO2 = Hb-bound O2 + dissolved O2

= [1.39a × Hb concentration × arterial O2 saturation] + [0.02b × paO2]

HR: heart rate; SV: stroke volume; Hb: haemoglobin.

Initially, peripheral tissues compensate for the reduced DO2I through increased O2 extraction, thus maintaining normal levels of O2 consumption (VO2) [3]. This mechanism cannot compensate for DO2I reductions below a critical level, beyond which VO2 declines to become ‘supply-limited’. Anaerobic metabolism and hyperlactataemia follows while organ function deteriorates in the face of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) depletion and a failure of ion pumps to maintain trans-membrane gradients and cell integrity.

Cellular and tissue hypoxia form a central element in development of multiple organ failure and activate the immune system through a number of mechanisms (see below) [4, 5]. Irrespective of initial cause, continued hypoperfusion and cellular ischaemia triggers complex cascades resulting in the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and leukocyte activation with the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proteolytic enzymes. Nuclear factor kappa-β (NF-kB), hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) play critical roles [6–10]. As a consequence, the vascular endothelium becomes permeable and expresses cellular adhesion molecules (CAM) and other inflammatory mediators [11, 12].

Low cardiac output-associated oxygendebt is associated with multiple organ failure (MOF) and mortality in post-operative patients [13]. The degree of tissue oxygen debt is similarly related to enhanced inflammatory responses, increased risk of acute lung injury and increased mortality [14]. Clinical studies demonstrate a causal relationship between traumatic injury and/or shock and a predisposition to sepsis/MOF, probably due to an excessive inflammatory response coupled with failure of cell-mediated immunity [15–17].

Hypovolaemic shock

Hypovolaemic shock is caused by a loss of circulating volume and/or non-haemorrhagic causes [2]. The latter include absolute loss of fluid (vomiting, diarrhoea, high-output fistulas or evaporative losses: fever, surgery, burns), or third space fluid sequestration through shifts between the intravascular and extravascular space (trauma, ileus, small bowel obstruction). The resulting decrease in intravascular volume reduces venous return, stroke volume and ultimately cardiac output causing tissue hypoperfusion.

Acute volume loss leads to the activation of compensatory mechanisms involving [18, 19]:

- volume and pressure receptors,

- the sympathetic nervous system (SNS),

- the renin-angiotensin (RAAS) system, and

- anti-diuretic hormone (ADH).

The earliest response arises from mainly atrial and pulmonary pressure receptors. The baroreceptor response and activation of the SNS produces arterial and venous vasoconstriction, and tachycardia. Venous vasoconstriction aims to restore preload and cardiac output, while arterial vasoconstriction increases mean arterial pressure (MAP). Blood flow is also diverted to vital organs (brain, heart, kidneys). Interstitium-to-intravascular space fluid shift (facilitated by reduced capillary pressures) also occurs and expands intravascular volume by as much as 1 litre in the first hour and a further 1 litre during the first 48 hours [20].

The RAAS is activated by the SNS and by a reduction in renal blood flow. Renin, released by the juxtaglomerular cells, leads to an increase in angiotensin II (AT-II). AT-II, a potent vasoconstrictor, stimulates the adrenal production of aldosterone, which in turn promotes renal sodium and water retention. ADH/vasopressin, a hormone secreted by the posterior pituitary, is a potent vasoconstrictor and increases water retention by the kidneys. These events increase circulating volume. During the later stages, erythropoietin is secreted to increase red cell volume and plasma protein synthesis is increased.

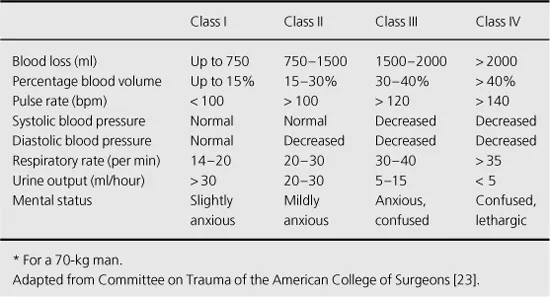

Healthy individuals can compensate for fluid losses of up to 30% of the circulating volume (Table 1.2). However, compensatory responses are highly variable and the ability to tolerate a reduction in cardiac output is greatly influenced by coexisting cardiovascular disease, autonomic neuropathy and medication such as beta-receptor antagonists.

Table 1.2 Estimated Fluid Loss in Haemorrhagic Shock*

Clinical features

The amount of volume loss chiefly determines the clinical picture. The presentation of hypovolaemic shock is that of a low cardiac output state. SNS activation causes vasoconstriction of cutaneous vessels and activation of sympathetic innervated sweat glands. Tachycardia, and pale, cold, clammy skin, or diaphoresis is clinically seen while capillary refill is reduced. Oliguria reflects a decreased renal perfusion pressure and insufficient compensatory mechanisms to minimise renal fluid losses. Similarly, cerebral hypoperfusion leads to agitation and later to coma. Respiratory compensation for the developing metabolic acidosis is evident as tachypnoea, often without a subjective feeling of shortness of breath.

Management

Managing a patient with shock requires a robust and organised team approach. The sequence of interventions is dictated by the presenting picture. As a general rule the aims of management are to maintain oxygenation, control bleeding and substitute circulating volume sufficiently to avoid significant cellular hypoxia, but without aiming for a normal blood pressure.

Resuscitation should be guided by clinical and laboratory makers of tissue perfusion (such as pH, lactate and base excess). Importantly, clinicians should remember that all of these markers share the disadvantage of being global indicators which show delayed normalisation during resuscitation. A trend towards improvement rather than full normalisation of these parameters is an appropriate short-term goal.

Although securing the airway and maintaining oxygenation is a priority in any critical condition, controlling the source of bleeding is the crucial first step in the management of haemorrhagic shock. This may have to be achieved by direct compression or rapid surgical intervention, occasionally prior to the restoration of circulating volume. Fluid resuscitation should, however, be commenced concurrently. Large bore intravenous access must be established rapidly and rapid infusing devices may be needed to keep up with losses. The source of bleeding may be external and obvious, but source identification may require investigations such as ultrasound scan, computed tomography (CT) or angiography.

In less severe bleeding or after the initial control of bleeding, at least partial restoration of circulating volume...