- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Designing and Assessing Courses and Curricula reflects the most current knowledge and practice in course and curriculum design and connects this knowledge with the critical task of assessing learning outcomes at both course and curricular levels. This thoroughly revised and expanded third edition of the best-selling book positions course design as a tool for educational change and contains a wealth of new material including new chapters, case examples, and resources.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Designing and Assessing Courses and Curricula by Robert M. Diamond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

A Frame of Reference

CHAPTER 1

A Learning-Centered Approach to Course and Curriculum Design

Too many Americans just aren’t getting the education that they need—and deserve.

United States Department of Education, 2006, vii.

As a faculty member, you can undertake very few activities that will have a greater impact on students than your active involvement in the design of a course or curriculum. As a direct result of these efforts, learning can be facilitated, your students’ attitudes toward their own abilities can be significantly enhanced and, if you’re successful, students will leave better prepared for the challenges they will face after graduation. In addition, because major course and curriculum designs tend to remain in place for years after the project has been completed, your efforts will impact far more students than you may anticipate at first.

The Curriculum Is Not Always Equal to or More Than the Sum of Its Parts

A growing number of authors report that too many of our students simply do not receive the quality of education that society expects and that the country needs for the years ahead. The educational experience of our college students has been described as disjointed, unstructured, and often outdated. Courses often have little relationship to the curriculum that is in place and may overlook the critical skills that students need to acquire.

The observations identified in the Association of American Colleges and Universities’ report, Integrity in the College Curriculum: A Report to the Academic Community (1985), are even more appropriate today than they were over twenty years ago: “As for what passes as a college curriculum, almost anything goes. We have reached a point at which we are more confident about the length of a college education than its content and purpose. Indeed, the major in most colleges is little more than a gathering of courses taken in one department, lacking structure and depth, as is often the case in the humanities and social sciences, or emphasizing content to the neglect of the essential style of inquiry on which the content is based, as is too frequently true in the natural and physical sciences.” The report continued, “The curriculum has given way to a marketplace philosophy; it is a supermarket where students are shoppers and professors are merchants of learning. Fads and fashions, the demands of popularity and success, enter where wisdom and experience should prevail. Does it make sense for a college to offer a thousand courses to a student who will only take thirty-six?” (p. 2).

The research, too, suggests that in many cases college and university curricula do not produce the results we intend. Curricula that are not focused by clear statements of intended outcomes often permit naive students broad choices among courses resulting in markedly different outcomes from those originally imagined: by graduation most students have come to understand that their degrees have more to do with the successful accumulation of credits than with the purposeful pursuit of knowledge (Gardiner, 1996, p. 34). In his 2006 essay on the status of innovation in American colleges and universities, Ted Marchese, former vice president of the Association for Higher Education and editor of Change magazine, made the following observation:

What’s at stake? Does this matter? Does it matter that university completion rates are 44 percent and slipping? That just 10 percent from the lowest economic quartile attain a degree? That figures released this past winter show huge chunks of our graduates who cannot comprehend a New York Times editorial or their own checkbook? That frustrated public officials edge closer and closer to imposing a standardized test of college outcomes? Does it matter that we look to our publics like an enterprise more eager for status and funding than self-inquiry and improvement? [2006].

Although his comments are certainly discomforting, they are accurate. Despite the efforts of many dedicated faculty and administrators and the support of numerous foundations, we are still not doing a particularly good job of educating our students. Too many of our graduates leave underprepared to be effective and productive citizens, and far too many students who enter college never graduate. As a result, America is losing out in many areas. Fewer and fewer citizens vote, we are perceived as an isolated country with little understanding of other cultures and of the world in general, and numerous other nations’ educators are doing a far better job of developing in their citizens the competence that will be required in the years ahead.

In the additional resources section at the end of this chapter you will find several publications that discuss in more detail the challenges that colleges and universities face.

In short, we have reached a point where we educators, in addition to becoming more efficient and effective, have to rethink at a basic level what we teach and how we teach. We must rethink our roles as faculty, how we can most effectively use the time and talents of our students, and how we can fully utilize the expanding capabilities of technology. The approach that we will use in this book is designed to help you do all of these things.

The Challenges of Curriculum and Course Design

Designing a quality course or curriculum is always difficult, time-consuming, and challenging. It requires thinking about the specific goals you have for your students, the demands of accreditation agencies, and about how you, as a teacher, can facilitate the learning process. This demanding task will force you to face issues that you may have avoided in the past, to test long-held assumptions with which you are very comfortable, and to investigate areas of research that may be unfamiliar to you. At times you may become tired and frustrated and wish to end the entire project. Just keep in mind how important this work is and press on. Despite the work involved most faculty who have used this model report that they found the process of design and implementation challenging, frequently exciting, and when completed, most rewarding.

Unfortunately, as important as these activities are, we faculty are seldom prepared to carry them out. Although you may have been fortunate enough to have participated in a strong, well-conceived program for teaching assistants, few faculty have had the opportunity to explore the process of course and curriculum design or to read the research that provides a solid base for these initiatives. This book is designed to help you go through the design, implementation, and evaluation processes. It will provide you with a practical, step-by-step approach supported by case studies, a review of the significant literature, and introduce you to materials that you should find extremely useful.

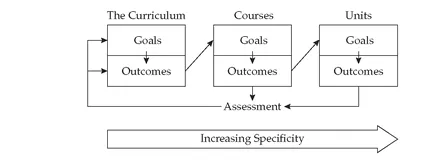

Figure 1.1.

From Goals to Outcomes to Assessment

An Important Relationship

As you follow through the steps of designing or revising a course or curriculum, it is extremely important to keep in mind the important relationship between goals, outcomes, and assessment. It is a relationship that remains a constant whether you are focusing on a curriculum, a course, or a unit or element within a course.

1. The outcome statements that are produced for the curriculum will be the basis on which the primary goals of each course within that curriculum are determined.

2. The outcome statements that are produced at the course level will be the basis on which the primary goals of each unit or element within that course are determined.

3. As you move from the curriculum to the courses within it, and to the individual units or elements within each course, the goal and outcome statements become more specific.

4. The success of your effort will be determined by how well your students meet the criteria for success as defined in the outcome statements at the course and unit or course element level. (See Figure 1.1.)

Getting Assistance

Although curriculum development is always a team activity, course design often is not. In both instances, however, the process can be facilitated and the end result improved if others are involved. These may include specialists in assessment or technology, other faculty or experts in the community, and although often overlooked, the registrar. In addition, we have found that having someone from outside your content area serve as a facilitator can be extremely useful. This individual may be a faculty member from another department or a staff member from the Academic Support Center on your campus. The facilitator, who has no vested content interest in the project, can help you explore options, ask key questions by challenging your assumptions, and get the important but often overlooked issues out in the open. Simply by not being in your discipline, facilitators can also put themselves in the position of your students and raise questions about assumptions and sequence. The importance of this role cannot be overstated. In Chapter 5 we discuss this function in some detail.

Course Design and the Delivery of Instruction

The best curriculum or course design in the world will be ineffective if we do not pay appropriate attention at the course level to how we teach and how students learn. Although faculty, employers, and governmental leaders agree that graduates need critical-thinking, complex problem-solving, communication, and interpersonal skills, research shows that the lecture is still the predominant method of instruction in U.S. higher education (Gardiner, 1996, pp. 38-39).

To ensure that students develop the higher-level competencies that you believe to be essential will require thinking about how you and your students spend time both inside and outside the classroom, what the responsibilities of your students should be, and how you will assess them during and at the end of courses, and at the conclusion of their total learning experience. It may also require rethinking your role as a faculty member. The chapters in this book on the design and delivery of instruction will describe the many options available to you, as well as the research on teaching and learning that can help inform your decisions.

Accountability

A major problem that all institutions face is the perception of business and governmental leaders, and of the public at large, that we have enthusiastically avoided stating clearly what competencies graduates should have and that, as a result, colleges and universities have provided little evidence that they are successful at what they are expected to do. Unfortunately, these perceptions are not far from the truth. The public demands for assessment of programs and institutions have, for the most part, fallen on deaf ears, and as a result of this inattention, higher education in general receives increasingly less support from the public and private sectors. While tuition has increased significantly, the quality of our product has not. As governors and other public leaders have made extremely clear, this problem of accountability needs to be addressed if support is to increase.

This demand for more information on the quality of learning at colleges and universities has led to many of the changes that are under way in accreditation, and to the increased attention being paid to learning outcomes and assessment by numerous national associations and institutions (see Chapter 2). As a result, collecting data and reporting results must be major elements in the process of course and curriculum design and implementation. One of the underlying assumptions in the work you will be doing is that the instructional goals you develop, and the assessment of your students’ success in reaching them, will be made public. Only this level of specificity can answer higher education’s severest critics. For this reason, as we move along we will d...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- PREFACE

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- PART ONE - A Frame of Reference

- PART TWO - The Process

- PART THREE - Designing, Implementing, and Assessing the Learning Experience

- PART FOUR - Your Next Steps

- RESOURCES

- CASE STUDIES

- REFERENCES

- INDEX