![]()

1

Introducing plants

In this chapter, we look at how plants originated, what floral diversity there is today and the make-up of the plant and its ultrastructure.

The beginning: the evolution of plants and the major divisions

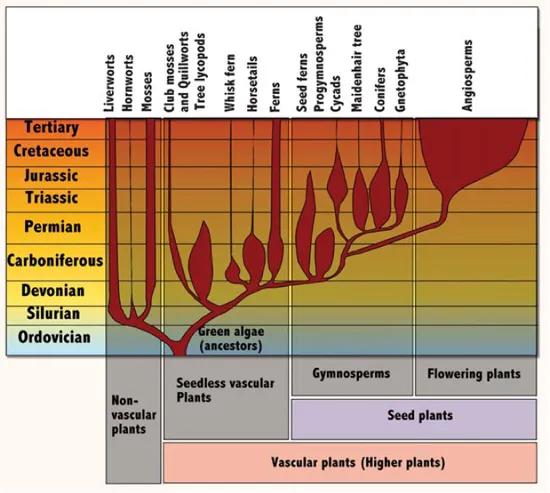

In the beginning, it is most probable that plants evolved from photosynthetic bacteria. From these bacteria the red and green algae evolved; and from freshwater-dwelling green algae the simple lower plants, such as mosses and ferns, evolved; and so on, up to the higher plants. A phylogenetic tree is shown in Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1 to demonstrate the relationship between the members of the plant kingdom and their relative abundance through the history of the planet.

Figure 1.1 Schematic diagram of the phylogeny of plants. The diagram shows the evolutionary relationship between the different species and the relative abundance in terms of species numbers (shown by the width of the dark red lineage tree). On the y axis the different time periods of the evolutionary history of plants are shown. The diagram is based on that presented by Ridge 2002.

Table 1.1 Estimates of numbers of species occurring in plant divisions.

| Hepatophyta | Liverworts | 6000 |

| Anthocerophyta | Hornworts | 100 |

| Bryophyta | Mosses | 10 000 |

| Lycophyta | Club mosses and quillworts | 1000 |

| Tree lycopods | | Extinct |

| Psilotum | Whisk fern | 3 |

| Equisetum | Horsetail | 15 |

| Pterophyta | Ferns | 11 000 |

| Peltasperms | Seed ferns | Extinct |

| Progymnosperms | | Extinct |

| Cycadophyta | Cycads | 140 |

| Ginkophyta | Maidenhair tree | 1 |

| Coniferophyta | Confers | 550 |

| Gnetophyta | Vessel-bearing gymnosperms | 70 |

| Angiosperms | Flowering plants | 23 5000 |

Conquering the land

The origin of plants was in water, where both photosynthetic bacteria and then algae originated. Light penetration of water reduces with depth, and on average only 1% of incident light reaches to a depth of over 15 m. As a consequence, there is a body of water at the surface known as the photic zone, where all of the photosynthetic activity in oceans occurs. A great deal of this photosynthetic activity still occurs at the shores of the oceans, where more complex algae have evolved; as a group these are commonly referred to as seaweeds. Algae are restricted to the oceans and freshwater bodies since, as part of the life cycle of algae, gametes (sex cells) that swim through water are required for sexual reproduction. This is thought to have been a major hindrance to plants attempting to colonize the land surface of the Earth and to overcome this, new reproductive systems needed to evolve.

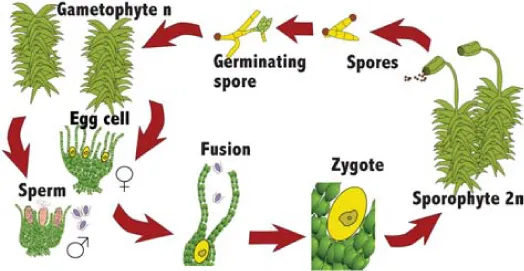

For the colonization of the land, methods of gamete transfer that were independent of water needed to evolve. Bryophytes (the mosses and liverworts), the first land-dwelling plants, still depend on moisture to complete their reproductive cycle (Figure 1.2). Sperm is released from haploid male gametophytes (a gamete-producing individual involved in the life cycle of bryophytes) which must swim to fuse with the egg cell of the haploid female gametophyte. This fusion yields a diploid zygote that divides to form a stalked cup-like structure, which releases haploid spores. These spores then form haploid male and female gametophytes. As a direct consequence of this life cycle and its requirement for water, mosses and liverworts are restricted to growing in moist habitats. In addition, these plants have no waterproof cuticle or vascular tissue, and are therefore very limited in their ability to transport water and carbohydrate made during photosynthesis to the rest of the plant. This makes it necessary for these plants to have a prostrate growth habit (rarely exceeding 2 cm in height), colonizing banks near to areas of water. Bryophytes do possess root-like structures known as rhizoids, but these are thought to have a function of anchorage rather than for transporting water to the aerial tissues. As a result of their inability to regulate water in the plant, bryophytes are poikilohydric; therefore, if the moisture declines in their habitat it also begins to decrease in their tissues. Some mosses can survive drying out but others need to be kept wet to survive. However, the ability to tolerate temporary drying of a habitat is a first step to colonizing dry land.

Figure 1.2 The life cycle of a bryophyte (mosses). There are around 10 000 different bryophyte species. The life cycle of bryophytes occurs in two phases, the sporophytic phase and the gametophytic phase. In the sporophytic phase the plant is diploid and develops as sporophyte. This releases spores which form gametophytes that are haploid. These form into separate sex gametophytes. The male gametophyte releases sperm, which is motile and swims towards the archegonium on the female gametophytes that bears the egg cells. These fuse to yield a zygote that then forms the sporophyte.

The mosses exhibit little ability to control water loss and if plants were ever to colonize a greater area of the land, the non-vascular plants needed to evolve solutions to this problem by developing a water transport system and a means of regulating water loss from the plant surface. The hornworts possess stomata on their leaf surfaces and therefore took the first steps to regulating water loss while maintaining gaseous exchange, which is essential for photosynthesis. These structures are absent in the mosses but present in more advanced plants. The prostrate growth of the mosses does not use light effectively and makes the damp habitat very competitive. As a consequence, there must have been a great selective pressure for structures to evolve in plants which raised the plants off the ground, which will have led to the evolution of a limited upright shoot in the bryophytes.

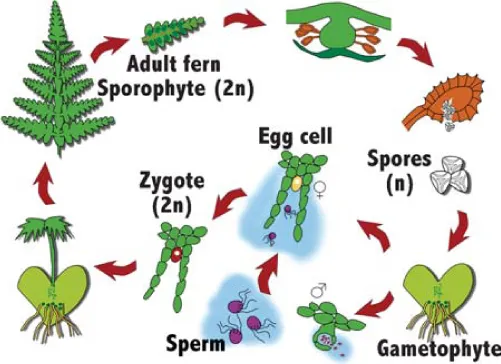

The evolution of the pteridophtyes (ferns) marked the development of a simple vascular tissue, allowing long-distance transport of water and carbohydrate around the plant. It also permitted the evolution of the upright shoot, thereby making taller plants possible. Ferns use a method for sexual reproduction similar to that of mosses (Figure 1.3). The adult fern plant is diploid and releases haploid spores, which divide and form male and female gametophytes. The male releases haploid mobile gametes, which swim and fuse with the female gametes to form diploid zygotes, which then divide to form the adult ferns. Pteridophytes possess distinct leaves, which enhance their ability to photosynthesize. Although the pteridophytes possess a water-resistant cuticle, they exhibit poor control of water loss from their leaves and in most instances are still restricted to moist habitats. The spores released by the adult ferns are tolerant of desiccation but movement of the male gamete still requires water. The ferns were the first plants to evolve lignin as a defence and support structure (see later). Plants that contain vascular tissue are frequently referred to as ’higher plants’.

Figure 1.3 The life cycle of a pteridophyte (ferns). The adult fern, or sporophyte, is diploid and on maturity releases spores from sori on the underside of leaves. These spores fall to the soil and germinate and from a gametophyte, also known as a thallus. This matures and forms an archegonium (where egg cells form) and an antheridium (where the sperm develops). The sperm are released and swim to the egg cells, with which they fuse to form diploid zygotes. The zygote then develops into an adult fern.

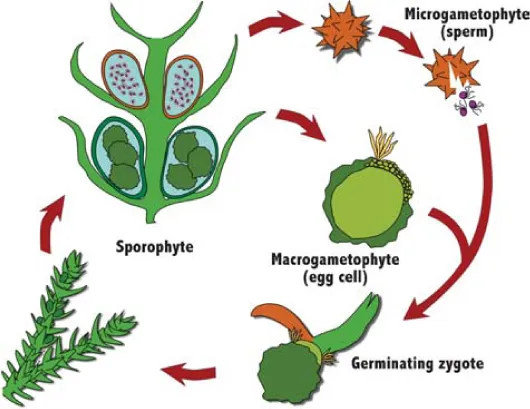

A small number of ferns and lycophytes exhibit heterospory (separate sex spores). In bryophytes and pteridophytes discussed so far, the spores are all identical. However, with heterosporous species the male sperm are formed from a microgametophyte and the female gamete from a macrogametophyte (Figure 1.4). The formation of separate sex gametophytes is considered to be one of the major steps towards the formation of plants that bear seeds.

Figure 1.4 The life cycle of a heterosporous pteridophyte. In a small number of instances species of ferns are heterosporous and this is thought to be a crucial evolutionary step in the formation of the flowering plants. In Figure 1.3 the egg cell and the sperm are the same size, but in heterosporous pteridophytes, the female gamete (macrogametophyte) is much larger than the male gamete (microgametophyte).

The habitat range of plants on land was widened considerably with the evolution of plants that produce seeds. The transition from being wholly aquatic to wholly terrestrial is considered complete in such plants. The seed-bearing plants are divided into two divisions, the gymnosperms (Pinophyta) and the angiosperms (flowering plants, Magnoliophyta). The angiosperms form the largest and most diverse plant division. Angiosperms produce reproductive structures in specialized organs called flowers, where the ovary and the ovul...