![]()

Part One

The Commercial Real Estate Money Pit

“Executives of major U.S. corporations, the leaders of public institutions, and millions of American homeowners are routinely held hostage by the construction industry to pay or face greater costs and delays.”

—Barry B. Lepatner

![]()

Chapter 1

The $500 Billion Black Hole

About 60 percent of the office space that companies pay so dearly for is now a dead zone of darkened doorways and wasting cubes.

—Mark Golan, vice president of real estate, Cisco Systems

In 2007, U.S. construction was estimated at $1.288 trillion—with more than 50 percent of that cost attributed to waste.1 If you’re skeptical, join the club. Some Mindshift members initially expressed the same skepticism. “There’s no way half the cost of building is waste!” But under the skepticism of owners and builders and contractors lies a real concern: I have no clue how to cut out 50 percent of my cost for a building.

The numbers are consistent, available to anyone who wants to take a close look,2 as we did. Because the first step to unlocking the mystery is to take a systematic look at the categories of waste. On virtually every construction project in the United States, we can trace this $500 billion black hole in the American economy back to two root causes: simple inefficiency and not-so-simple bad behavior.

WHY THE DESIGN-BUILD MODEL IS DEAD

The industry’s traditional model for building—“design-bid-build (DBB),” solidified in the 1950s with the American Institute of Architects (AIA’s) establishment of distinct phases for a project: schematic (concept), design development, construction documentation, and construction administration. The process follows a logical linear progression: design a building, assemble a team to build it, and implement the plans. Sounds like a reasonable idea, and for many years it was. The DBB delivery method began to falter in the 1960s with serious cracks by the 1970s. These cracks are evidenced by the introduction of alternative delivery models each attempting to remedy one of DBB’s shortcomings.

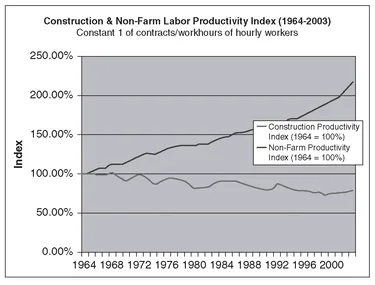

Construction paralleled manufacturing gains in productivity right up until 1964, when it hit a roadblock. From that date forward manufacturing consistently improves, but construction productivity slowly declines. By 2003, the Bureau of Labor Statistics measured a 275 percent gap between manufacturing gains and construction declines (Figure 1.1). What happened?

Figure 1.1 Department of Labor Productivity Gap Between Construction and Manufacturing

Source: US Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of Labor Statistics

A number of factors explain the divergence, including fundamental changes in the economy.3 The post-World War II expansion and baby boom peaked, and the information economy began to surpass manufacturing. Beginning in 1973, the recession pushed architects and engineers to move from a craft practice model to a professional services model, adopting fee structures similar to lawyers and accountants. Emphasis shifted away from the master-builder role, where the architect not only designed but supervised construction, to a specialist mentality that focused on the architect’s unique business capability in design.4 Contractors also began to deal with shrinking margins and higher risk by migrating away from performing the work with their own employees to becoming labor brokers.

Way back in the 1970s, Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock was prescient in identifying the factor most responsible for the decline of the design-bid-build delivery method: a need for speed. Back in the days before cell phones and personal computers, Toffler described a new world that would be qualitatively different from past eras. This new economy would be based on information and driven by change. It would require speed and flexibility. This way of doing things would be like a Ferrari, hugging the road and taking the turns with ease. Unfortunately, the design-bid-build process was a Lincoln Town Car—built for quality and a comfortable ride, but not much good on the hairpin turns and switchbacks of the brave new world that we live in today.

The paradigm has changed, and the building industry is scrambling to catch up. The speed-to-market business driver has forced a conflicting trade-off between quality, cost, and time.5 During the last 30 years or so, we have experimented with several variations of the design-bid-build model, looking for better ways to address the speed-to-market demand without sacrificing quality, compromising the owner’s intent, inflating costs, or putting the project or a key stakeholder at undue risk. Owners have a choice of the first two variables, but they must allow the construction team to control the third. In addition to process waste there is waste in the end product. According to Mark Golan, vice president of worldwide real estate, Cisco Systems,6 “About 60 percent of the office space that companies pay so dearly for is now a dead zone of darkened doorways and wasting cubes.” This is not the result we want.

Mindshift took a close look at all of the different delivery models and concluded that most are variations of DBB that seek to bring harmony to the three variables of cost, schedule, and quality. They take the same familiar approach—assembling fragmented collections of companies, selected independently and most often based on low bids. These solutions not only do not solve the problem, they compound it, resulting in more of what we don’t want: waste.

WHERE THE WASTE COMES FROM

A very visible form of waste comes from inaccurate information that creeps into projects with multiple specialties gathering and regathering the same data during a project.

7 But less visible and much more ingrained sources of waste come from the structural components that govern our industry:

• lack of time

• silos (vertically organized departments or organizations that work without consideration of other interdependent entities)

• boilerplate planning

• sub-trade coordination

• hierarchical dilution

• phase-induced ignorance

• problems that come with fielding a new team with every project

Robert A. Humphrey said, “An undefined problem has an infinite number of solutions.” Before we go any further, then, let’s see if we can define the problem.

LACK OF TIME

“Haste makes waste” in a system designed to function as a sequence of distinct phases. DBB no longer reflects the fluid reality of a project. Most buildings commence construction before architectural plans are completed. One colleague attributes the majority of the problems he has experienced with projects using this phased approach to the lack of time invested in the design phase. We will see in the third section of the book the need for owners to bring their team on board even prior to design to assist with the business plan for the project. Architect Paul Adams sums it up: “All the big mistakes are made in the first day.”8

Rushed implementation ranks as the next most common complaint after the bid process itself. Brokers are key contributors to the lack of planning time given to the design and construction process. They are trained to get the best deal on a new building or a lease, and often they do not appreciate the details and time necessary to plan and coordinate construction and the move. The commission brokers are paid for the transaction has no tie to the success of the transition. Some brokers see their role in the larger context. Those brokers are often essential team makers and team leaders. These are individuals who rise above the industry’s fragmentation and go against a compensation structure that narrowly rewards completing the lease transaction.

The owner of one national project management firm noted that the narrow role and incentive of the broker affects more than single-transaction accounts. His firm works side-by-side with a brokerage firm on a multi-year, multi-site account. The project management firm has documented the need for five weeks to design and deliver a space once the lease is signed. Despite several mutual meetings with the client and broker, the average time allowed is three weeks. Contributing to this lack of coordination are the different departments that the broker and project management firm reports to. The results are predictable. Each project requires more time, experiences errors and cost overruns, and creates a high level of conflict. When projects run into problems, the broker is long gone working on the next transaction, and the project management firm is front and center taking the criticism. Fragmentation is the true culprit and reason the client has yet to make the connection that the handoff from the broker determines if the project is successful or problematic.

A general contractor noted another common omission: Capital equipment and long lead-time items are commonly overlooked by the owner and not factored in to the bid schedule. In one case, the contractor won a project requiring several chillers. The owner expected and counted on a four-month construction schedule based on the architect’s estimated timeline. What they did not consider was the five-month lead-time to purchase and produce the chillers, and the additional month to connect the piping and make them operational. The general contractor commented that had they used the five-week bid process for intense pre-construction analysis and planning the owner could have achieved the desired outcome and saved several million dollars due to delays and fixing errors on the job.

SILOS

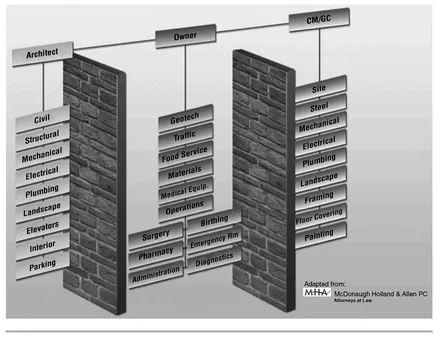

If you’ve ever been to the Midwest, you know what a silo is: a vertical storage facility dedicated to protect one product and one product only, with only one way in or out, and with no connection to any of the other silos that dot the land. Sadly, this also describes the building industry (see Figure 1.2).

Planning a new facility involves many stakeholders, all narrowly focused on their different interests. In general, the user groups focus on how much space they need and their budget, the real estate group focuses on optimizing the capital they have allocated and on ways to lower operational costs. Other departments—including information technology, tax department, human resources, and marketing—also have an interest in the new facility, and may contribute to the final solution. Unfortunately, few companies have a defined process for sorting through all of these different and, usually, competing interests; and few consultants have the expertise to sort through this complexity in a rapid or cost-effective way.9 The result is an awkward analysis and business planning process that ends up with little more than a head count, a wish list of desired features, a capital budget, and a timeline.

Figure 1.2 Silos

Now it’s the architect’s turn. He or she must reconcile a broad wish list with an inadequate fee for the services required to provide a thorough assessment, an insufficient capital budget to fulfill the wish list, and a project that is already behind schedule.

If the silos inside the owner’s company produce a plan based on speculative assumptions, unreconciled conflicting demands, floating priorities, and wishful expectations, it must then augur through additional silos—including the interests of the owner, the architect, the general contractor, and their agents. Those interests are separated by walls governed by legal and insurance concerns and filtered through different business cultures, methodologies, and missions.

The owner’s mission is to get a facility that meets their needs as close to the budget and schedule as possible. The architect’s mission is to get the most bang for the buck with the budget and parameters the owner sets. The general contractor will attempt to build what the architect and owner design, while managing the many variables that impact construction and increasing their fee to cover potential unknowns.

There is a built-in tension between the three parties. The owner will adjust as much as they can to take into account changing business needs. The architect will wait as long as they can to lock into a final plan responding to owner adjustments or contractor suggestions to lower cost or improve constructability. The general contractor will attempt to secure earlier decisions or increase their contingency fee. These separations restrict the flow of information, delay decisions, create conflict, end in adversarial relationships, and turn natural allies into enemies.

This adversarial behavior is better understood by looking at the larger system.10 When teams work well, each member works toward the success of the other. That success, however, is the result of more than good rapport. Reinforcing positive behavior is a feature of a well-designed system. Members first understand the different processes others use to get their work accomplished and therefore understand how their actions can aid or detract from that work.11 Secondly, members have a clear understanding that the benefits of team success outweigh individual success. In fact, members see clearly that a narrow focus on individual success not only limits but also can derail team success. Even casual sports observers see how this dynamic plays out.

The term for this among systems theorists is “accidental adversaries.” Kyle Davy explains, “When our mutual success depends on one another we unwittingly work against each other and become adversaries further eroding our mutual chances for success.” One contractor described this as “three ticks and no dog.”

During a Mindshift retreat, our facilitator, Kyle Davy, walked us through a common scenario of accidental adversaries. Architects and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing engineers (MEPs) should be natural allies. Their mutual work should lead to tighter alignment and cooperation. Instead, if you ask MEPs which entity creates their greatest turmoil, they point immediately to architects. If you ask an architect the same question they immediately point to the MEP.

The problem occurs when each follows an internal success logic creating unintended impacts on their partner. The architect, for example, sees design as a constant search integrating new information to improve the design. Constant change and searching for a better solution becomes an exercise in futile rework for the MEP. The MEP views change not as an improvement in design but as a partner who can’t make up their mind or control their client.

MEPs are impacted because they have to scrap their work and start over. The internal l...