![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

“Proof,” I said, “is always a relative thing. It's an overwhelming balance of probabilities. And that's a matter of how they strike you.”

(Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely, 1940)

Probability is the rule of life—especially under the skin. Never make a positive diagnosis.

(Sir William Osler)

Thoughtful clinicians ask themselves many difficult questions during the course of taking care of patients. Some of these questions are as follows:

- How may I be thorough yet efficient when considering the possible causes of my patient's problem?

- How do I characterize the information I have gathered during the medical interview and physical examination?

- How should I interpret new diagnostic information?

- How do I select the appropriate diagnostic test?

- How do I choose among several risky treatments?

The goal of this book is to help clinicians answer these important questions.

The first question is addressed with observations from expert clinicians “thinking out loud” as they work their way through a clinical problem. The last four are addressed from the perspective of medical decision analysis, a quantitative approach to medical decision making.

The goal of this introductory chapter is to preview the contents of the book by sketching out preliminary answers to these five questions.

1.1 How may I be thorough yet efficient when considering the possible causes of my patient's problems?

Trying to be efficient in thinking about the possible causes of a patient's problem often conflicts with being thorough. This conflict has no single solution. However, much may be learned about medical problem solving by listening to expert diagnosticians discuss how they reasoned their way through a case. Because the single most powerful predictor of skill in diagnosis is exposure to patients, the best advice is “see lots of patients and learn from your mistakes.” How to be thorough, yet efficient, when thinking about the possible causes of a patient's problem is the topic of Chapter 2.

1.2 How do I characterize the information I have gathered during the medical interview and physical examination?

The first step toward understanding how to characterize the information one gathers from the medical interview and physical examination is to realize that information provided by the patient and by diagnostic tests usually does not reveal the patient's true state. A patient's signs, symptoms, and diagnostic test results are usually representative of more than one disease. Therefore, distinguishing among the possibilities with absolute certainty is not possible. A 60-year-old man's history of chest pain illustrates this point:

Mr. Costin, a 60-year-old bank executive, walks into the emergency room complaining of intermittent substernal chest pain that is “squeezing” in character. The chest pain is occasionally brought on by exertion but usually occurs without provocation. When it occurs, the patient lies down for a few minutes, and the pain usually subsides in about 5 minutes. It never lasts more than 10 minutes. Until these episodes of chest pain began 3 weeks ago, the patient had been in good health, except for intermittent problems with heartburn after a heavy meal.

Although there are at least 60 causes of chest pain, Mr. Costin's medical history narrows down the diagnostic possibilities considerably. Based on his history, the two most likely causes of Mr. Costin's chest pain are coronary artery disease or esophageal disease.

However, the cause of Mr. Costin's illness is uncertain. This uncertainty is not a shortcoming of the clinician who gathered the information; rather, it reflects the uncertainty inherent in the information provided by Mr. Costin. Like most patients, his true disease state is hidden within his body and must be inferred from imperfect external clues.

How do clinicians usually characterize the uncertainty inherent in medical information? Most clinicians use words such as “probably” or “possibly” to characterize this uncertainty. However, most of these words are imprecise, as illustrated as we hear more about Mr. Costin's story:

The clinician who sees Mr. Costin in the emergency room tells Mr. Costin, “I cannot rule out coronary artery disease. The next step in the diagnostic process is to examine the results of a stress ECG.” She also says, “I cannot rule out esophageal disease either. If the stress ECG is negative, we will work you up for esophageal disease.”

Mr. Costin is very concerned about his condition and seeks a second opinion. The second clinician who sees Mr. Costin agrees that coronary artery disease and esophageal disease are the most likely diagnoses. He tells Mr. Costin, “Coronary artery disease is a likely diagnosis, but to know for certain we'll have to see the results of a stress ECG.” Concerning esophageal disease, he says, “We cannot rule out esophageal disease at this point. If the stress ECG is normal, and you don't begin to feel better, we'll work you up for esophageal disease.”

Mr. Costin feels reassured that both clinicians seem to agree on the possibility of esophageal disease, since both have said that they cannot rule it out. However, Mr. Costin cannot reconcile the different statements concerning the likelihood that he has coronary artery disease. Recall that the first clinician said “coronary artery disease cannot be ruled out,” whereas the second clinician stated, “coronary artery disease is a likely diagnosis.” Mr. Costin wants to know the difference between these two different opinions. He explains his confusion to the second clinician and asks him to speak to the first clinician:

The two clinicians confer by telephone. Although the clinicians expressed the likelihood of coronary artery disease differently when they talked with Mr. Costin, it turns out that they had similar ideas about the likelihood that he has coronary artery disease. Both clinicians believe that about one patient out of three with Mr. Costin's history has coronary artery disease.

From this episode, Mr. Costin learns that clinicians may choose different words to express the same judgment about the likelihood of an uncertain event:

To Mr. Costin's surprise, the clinicians have different opinions about the likelihood of esophageal disease, despite the fact that both clinicians described its likelihood with the same phrase, “esophageal disease cannot be ruled out.” The first clinician believes that among patients with Mr. Costin's symptoms, only one patient in ten would have esophageal disease. However, the second clinician thinks that as many as one patient in two would have esophageal disease.

Mr. Costin is chagrined that both clinicians used the same phrase, “cannot be ruled out,” to describe two different likelihoods. He learns that clinicians commonly use the same words to express different judgments about the likelihood of an event.

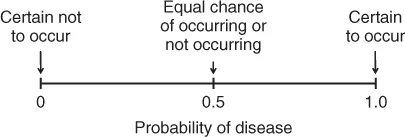

The solution to the confusion that can occur when using words to characterize uncertainty with words is to use a number: probability. Probability expresses uncertainty precisely because it is the likelihood that a condition is present or will occur in the future. When one clinician believes the probability that a patient has coronary artery disease is 1 in 10, and the other clinician thinks that it is 1 in 2, the two clinicians know that they disagree and that they must talk about why their interpretations are so disparate. The precision of numbers to express uncertainty is illustrated graphically by the scale in Figure 1.1. On this scale, uncertain events are expressed with numbers between 0 and 1.

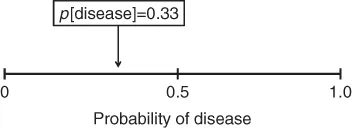

To understand the meaning of probability in medicine, think of it as a fraction. For example, the fraction “one-third” means 33 out of a group of 100. In medicine, if a clinician states that the probability that a disease is present is 33%, it means that the clinician believes that if she sees 100 patients with the same findings, 33 of them will have the disease in question (Figure 1.2).

Although probability has a precise mathematical meaning, a probability estimate need not correspond to a physical reality, such as the prevalence of disease in a defined group of patients. We define probability in medicine as a number between 0 and 1 that expresses a clinician's opinion about the likelihood of a condition being present or occurring in the future. The probability of an event a clinician believes is certain to occur is equal to 1. The probability of an event a clinician believes is certain not to occur is equal to 0.

A probability may apply to the present state of the patient (e.g., that he has coronary artery disease), or it may be used to express the likelihood that an event will occur in the future (e.g., that he will experience a myocardial infarction within one year).

Any degree of uncertainty may be expressed on this scale. Note that uncertain events are expressed with numbers between 0 and 1. Both ends of the scale correspond to absolute certainly. An event that is certain to occur is expressed with a probability equal to 1. An event that is certain not to occur is expressed with a probability equal to 0.

When should a clinician use probability in the diagnostic process? The first time that probability is useful in the diagnostic process is when the clinician feels she needs to synthesize the medical information she has obtained in the medical interview and physical examination into an opinion. At this juncture the clinician wants to be precise about the uncertainty because she is poised to make decisions about the patient. The clinician may decide to act as if the patient is not diseased. She may decide that she needs more information and will order a diagnostic test. She may decide that she knows enough to start the patient on a specific treatment. To decide between these options, she does not need to know the diagnosis. She does need to estimate the patient's probability that he has, as in the case of Mr. Costin, coronary artery disease as the cause of his chest pain.

A clinician arrives at a probability estimate for a disease hypothesis by using personal experience and the published literature. Advice on how to estimate probability is found in Chapter 3.

1.3 How do I interpret new diagnostic information?

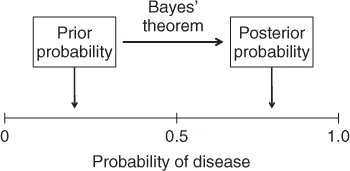

New diagnostic information often does not reveal the patient's true state, and the best a clinician can do is to estimate how much the new information has changed her uncertainty about it. This task is difficult if one is describing uncertainty with words. However, if the clinician is expressing uncertainty with probability, she can use Bayes' theorem to estimate how much her uncertainty about a patient's true state should have changed. To use Bayes' theorem a clinician must estimate the probability of disease before the new information was gathered (the prior probability or pre-test probability) and know the accuracy of the new diagnostic information. The probability of disease that results from interpreting new diagnostic information is called the posterior probability (or post-test probability). These two probabilities are illustrated in Figure 1.3.

Chapter 4 describes how to use Bayes' theorem to estimate the post-test probability of a disease.

1.4 How do I select the appropriate diagnostic test?

Although the selection of a diagnostic test is ostensibly straightfor...