How to be a Quantitative Ecologist

The 'A to R' of Green Mathematics and Statistics

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

How to be a Quantitative Ecologist

The 'A to R' of Green Mathematics and Statistics

About this book

How to be a Quantitative Ecologist: The 'A to R' of Green Mathematics and Statistics

Ecological research is becoming increasingly quantitative, yet students often opt out of courses in mathematics and statistics, unwittingly limiting their ability to carry out research in the future. This textbook provides a practical introduction to quantitative ecology for students and practitioners who have realised that they need this opportunity.

The text is addressed to readers who haven't used mathematics since school, who were perhaps more confused than enlightened by their undergraduate lectures in statistics and who have never used a computer for much more than word processing and data entry. From this starting point, it slowly but surely instils an understanding of mathematics, statistics and programming, sufficient for initiating research in ecology. The book's practical value is enhanced by extensive use of biological examples and the computer language R for graphics, programming and data analysis.

Key Features:

- Provides a complete introduction to mathematics statistics and computing for ecologists.

- Presents a wealth of ecological examples demonstrating the applied relevance of abstract mathematical concepts, showing how a little technique can go a long way in answering interesting ecological questions.

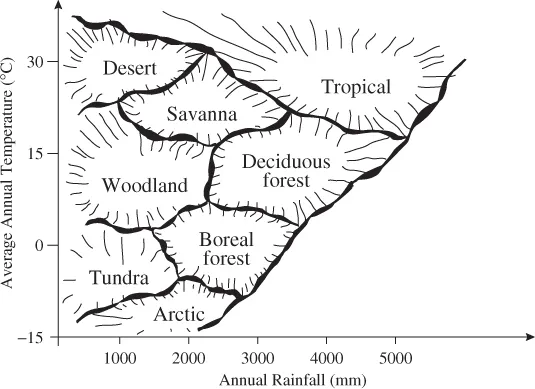

- Covers elementary topics, including the rules of algebra, logarithms, geometry, calculus, descriptive statistics, probability, hypothesis testing and linear regression.

- Explores more advanced topics including fractals, non-linear dynamical systems, likelihood and Bayesian estimation, generalised linear, mixed and additive models, and multivariate statistics.

- R boxes provide step-by-step recipes for implementing the graphical and numerical techniques outlined in each section.

How to be a Quantitative Ecologist provides a comprehensive introduction to mathematics, statistics and computing and is the ideal textbook for late undergraduate and postgraduate courses in environmental biology.

"With a book like this, there is no excuse for people to be afraid of maths, and to be ignorant of what it can do."

—Professor Tim Benton, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Leeds, UK

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Thank You

- Chapter 0: How to Start a Meaningful Relationship with Your Computer

- Chapter 1: How to Make Mathematical Statements

- Chapter 2: How to Describe Regular Shapes and Patterns

- Chapter 3: How to Change Things, One Step at a Time

- Chapter 4: How to Change Things, Continuously

- Chapter 5: How to Work with Accumulated Change

- Chapter 6: How to Keep Stuff Organised in Tables

- Chapter 7: How to Visualise and Summarise Data

- Chapter 8: How to Put a Value on Uncertainty

- Chapter 9: How to Identify Different Kinds of Randomness

- Chapter 10: How to See the Forest from the Trees

- Chapter 11: How to Separate the Signal from the Noise

- Chapter 12: How to Measure Similarity

- Appendix: Formulae

- Author Index

- Subject Index