eBook - ePub

Pediatric Non-Clinical Drug Testing

Principles, Requirements, and Practice

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pediatric Non-Clinical Drug Testing

Principles, Requirements, and Practice

About this book

This book explains the importance and practice of pediatric drug testing for pharmaceutical and toxicology professionals. It describes the practical and ethical issues regarding non-clinical testing to meet US FDA Guidelines, differences resulting from the new European EMEA legislation, and how to develop appropriate information for submission to both agencies. It also provides practical study designs and approaches that can be used to meet international requirements. Covering the full scope of non-clinical testing, regulations, models, practice, and relation to clinical trials, this text offers a comprehensive and up-to-date resource.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pediatric Non-Clinical Drug Testing by Alan M. Hoberman, Elise M. Lewis, Alan M. Hoberman,Elise M. Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Children, like adults, benefit from the continuing advances in biomedical research, including the use of animal models, to evaluate the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products, medical devices, and biopharmaceuticals. These advances in biomedical research are central to the ongoing improvements in medical care and public health policies that are intended to prevent or lower the incidence of childhood illnesses or diseases, improve the quality of life for pediatric patients, and ultimately, save or prolong the lives of millions of children around the world. Despite these advances, the looming concern is that children do not benefit equally from these overall advances in biomedical research. This is demonstrated by the continued “off-label” use of medicines to treat childhood illnesses and diseases and the lack of investment in formulations specifically for children regardless of legislative progress [1]. This problem is illustrated by the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that nearly 9 million children younger than 5 years and more than 1.8 million young people older than 15 years die each year and an even greater number of young people suffer from illnesses that hinder their normal growth and development [2].

To understand the full complexity of this problem, one must be aware of the various illnesses or disabilities that affect “children,” a grouping that includes all individuals from preterm newborn infants to 18-year-old adolescents. As shown in Table 1.1, diseases that can occur in the pediatric population include, but are not limited to, bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections; nutritional diseases; congenital anomalies; cancer; or diseases of the various organ systems (e.g., immune, nervous, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, respiratory, or urogenital). Some of the most common childhood illnesses are presented in Table 1.2. As mentioned by Crosse “Although children suffer from many of the same diseases as adults and are often treated with the same drugs, only about one-third of the drugs that are prescribed for children have been studied and labeled for pediatric use” [3].

Table 1.1 Disease States Observed in Children

Source: Modified from Ref. 90

|

|

Table 1.2 Common Childhood Illnesses

|

|

The “off-label” use of medicines and lack of investment in pediatric formulations is not a new issue. The clinical aspect of developing, and using, therapeutic agents and surgical treatments in preadult patients has been, and continues to be, a complicated and controversial medical problem. Approximately 40 years ago, children were referred to as therapeutic orphans [4], a phrase that was coined by Dr. Harry Shirkey because of excessive use of the pediatric disclaimer clause (i.e., “not to be used in children, since clinical studies have been insufficient to establish recommendations for its use” [5]) in drug labels following an amendment in 1962 to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Law [6]. The term “therapeutic orphan” remains relevant today [6, 7], as it purports two ethical dilemmas that physicians are frequently challenged with: (i) depriving infants, children, or adolescents of potentially beneficial therapies because of an apparent information gap [7] and (ii) prescribing medicines on the basis of prior experience(s) and extrapolating doses on the basis of data generated in adult patients [8].

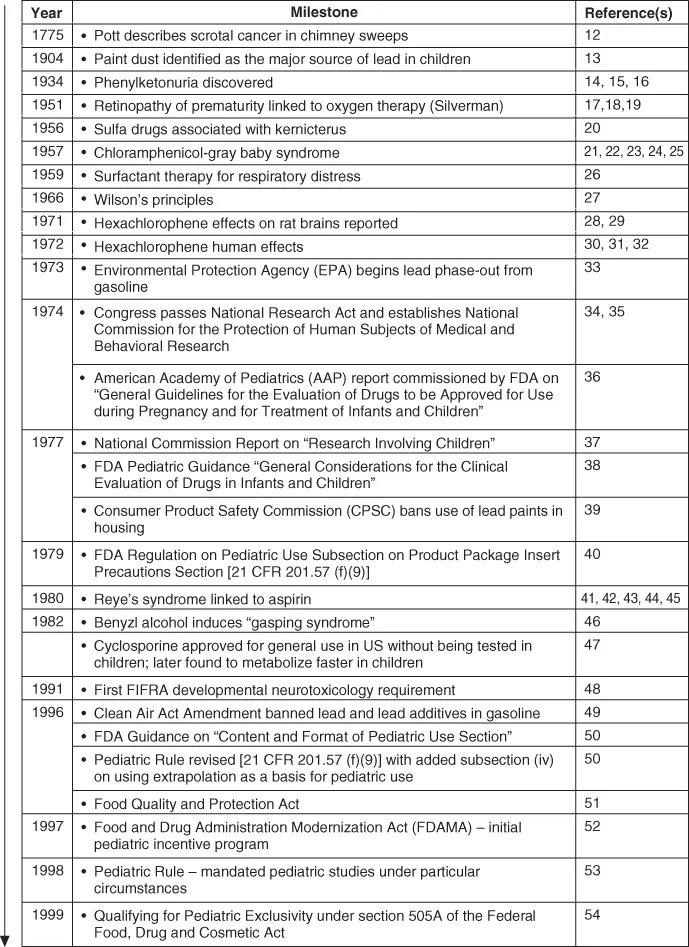

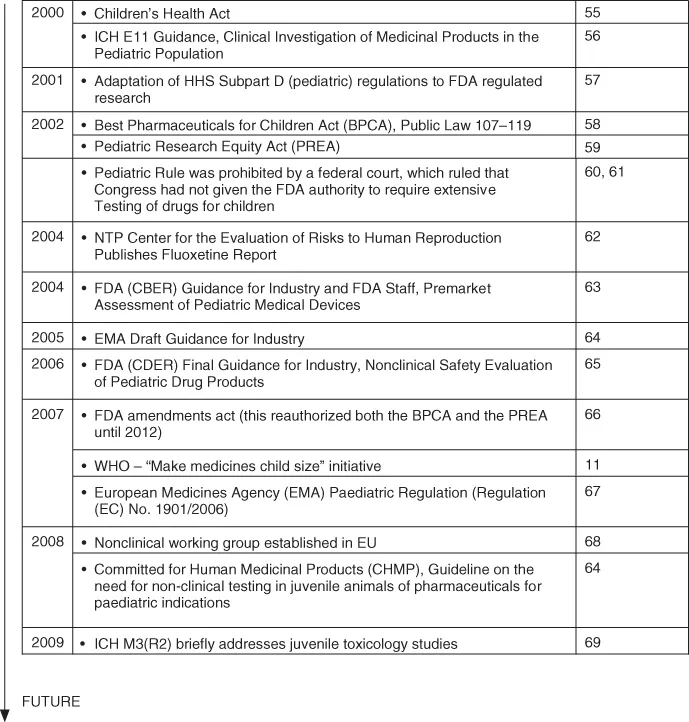

More recently, the phrase “canaries in the mineshafts” [9, 10] has been applied to this vulnerable population because children “die more quickly and in greater numbers from therapeutic mishaps” [9]. These mishaps include, but are not limited to, overdosing resulting in potential toxicity or underdosing resulting in potential inefficacy [11]. Several examples that resulted in legislative changes regarding pediatric drug development are outlined in Fig. 1.1. While legislative changes are welcomed by proponents of pediatric medicine and they provide the mechanisms necessary to acquire information on pediatric safety and efficacy to improve product labeling, the overall progress throughout the industry has been slower than desired, in part, because the pediatric population represents a small market within the drug development community.

Figure 1.1 Benchmarks in the regulation of pediatric drug development. Source: Modified from [70, 71].

We all agree that a “child is not a small adult” [37] and children should not be considered a “homogenous category” [37]. While it is obvious that children rapidly change and develop physically, cognitively, and emotionally [8] from birth to adulthood, there are inherent kinetic differences between children and adults that could result in over- or underexposure to medicinal products. In children, growth and development can affect the process by which a drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted from the body. In addition, protein binding can be affected by age. Some notable differences observed in children compared to adults include (i) immaturity of the renal and hepatic clearance mechanisms; (ii) immaturity of the blood–brain barrier, higher water content, and greater surface area in the bodies of infants; (iii) unique susceptibilities observed in newborns; (iv) rapid and variable maturation of physiologic and pharmacologic processes; (v) organ functional capacity; and (vi) changes in receptor expression and function [72, 73]. As noted by Brent [74], “in many instances environmental toxicants will exploit the vulnerabilities and sensitivities of developing organisms. In other instances, there will be no differences between the developing organism and the adult when exposed to toxicants, and in some instances the children and adolescents may even withstand the exposures with less insult.” Examples of drugs that demonstrate different toxicities in adult and pediatric populations are summarized in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Examples of Drugs that Exhibit Different Toxicities in Pediatric and Adult Populations

| Ages Most | ||

| Drug | Observations | Affected |

| Acetaminophen | Overdose results in death from liver toxicity; children possess a higher rate of glutathione turnover and more active sulfation | Adult |

| α-Interferon | Spastic diplegia | Infant |

| Aminoglycosides | In infants with Clostridium botulinum, the gastrointestinal tracts may have increased neuromuscular blockade and prolonged severity of the paralytic phase | Infant |

| Vestibular balance and hearing deficiencies as well as renal disease | Adult | |

| Aspirin | Results in alkalosis, acidosis, respiratory distress, and death | Child |

| β-Blockers | May cause hypoglycemia | Infant/Child |

| Chloramphenicol | Results in “gray baby syndrome” with vascular collapse and death; immature liver fails to ... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Overview of Pediatric Diseases and Clinical Considerations on Developing Medicines for Children

- Chapter 3: Nonclinical Safety Assessment for Biopharmaceuticals: Challenges and Strategies for Juvenile Animal Testing

- Chapter 4: FDA Approach to Pediatric Testing

- Chapter 5: Pediatric Drug Development Plans

- Chapter 6: Application of Principles of Nonclinical Pediatric Drug Testing to the Hazard Evaluation of Environmental Contaminants

- Chapter 7: Nonclinical Testing Procedures—Pharmacokinetics

- Chapter 8: Preclinical Development of a Pharmaceutical Product for Children

- Chapter 9: Juvenile Toxicity Study Design for the Rodent and Rabbit

- Chapter 10: Dog Juvenile Toxicity

- Chapter 11: Use of the Swine Pediatric Model

- Chapter 12: Juvenile Immunodevelopment in Minipigs

- Chapter 13: Use of Primate Pediatric Model

- Chapter 14: Approaches to Rat Juvenile Toxicity Studies and Case Studies: a Pharmaceutical Perspective

- Appendix I: Maturation of Organ Systems in Various Species

- Appendix II: Sample Juvenile Toxicity Testing Protocol

- Index