- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Greek Religion

About this book

Ancient Greek Religion provides an introduction to the fundamental beliefs, practices, and major deities of Greek religion.

- Focuses on Athens in the classical period

- Includes detailed discussion of Greek gods and heroes, myth and cult, and vivid descriptions of Greek religion as it was practiced

- Ancient texts are presented in boxes to promote thought and discussion, and abundant illustrations help readers visualize the rich and varied religious life of ancient Greece

- Revised edition includes additional boxed texts and bibliography, an 8-page color plate section, a new discussion of the nature of Greek "piety, " and a new chapter on Greek Religion and Greek Culture

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Greek Religion by Jon D. Mikalson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Ancient Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

FIVE MAJOR GREEK CULTS

Athena Polias of Athens

Demeter Eleusinia and the Eleusinian Mysteries

Dionysus Cadmeios of Thebes

Apollo Pythios of Delphi

Zeus Olympios of Olympia

Athena Polias of Athens

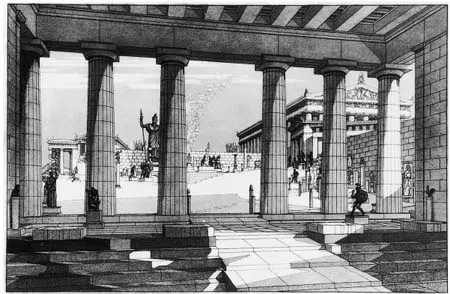

The Acropolis of Athens was enclosed by a large fortification wall with one major gateway on the west side (Plate 1). It was thus a temenos, and it was viewed, as a whole, as the sanctuary of Athena. If one had any doubt of this, he needed only look before him as he passed through the gateway. There stood squarely facing him, about forty meters away, a nine-meter tall bronze statue of a fully armed Athena.

For our visitor Athena’s Great Altar, which was the religious center of her cult, lay at the far, east end of Acropolis. It was perhaps 15 meters in width and 8.5 meters in depth, and it was there that prayers would be made and offerings would be burned in the goddess’ honor at her festival of the Panathenaea and on other occasions. In the early fifth century this altar stood directly east of the Temple of Athena, but this “old” temple of Athena was at least partially destroyed by the Persians in 480 B.C.E. In the fifth-century rebuilding of the Acropolis, the old temple was replaced by a new temple, the building which we for convenience will call the Erechtheum. The Erechtheum was built just to the north of the old temple, and

Figure 4.1 A “new-style” four-drachma ($400) Athenian silver coin from the late second century B.C.E. The head of Athena is probably modeled on that of Phidias’ statue of Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon. With permission of the Royal Ontario Museum, ©ROM.

Figure 4.2 View through the Propylaea (gateway) of the Athenian Acropolis, with the Parthenon on the right, the Erechtheum on the left, the Athena Promachos statue by Phidias in the center left, and smoke rising from the Altar of Athena Polias in the far distance. Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations.

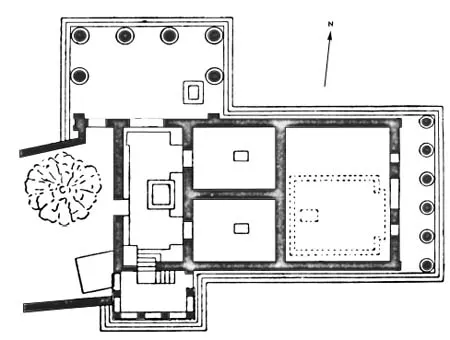

so, uncharacteristically, did not align perfectly with the Great Altar. The plan of the Erechtheum was unusual. The east end, facing the Altar, is usual, but what should be the west end has been swung around as a porch at a lower level facing north, and another porch, supported by columns in the form of women (Caryatids, hence the Caryatid Porch), was added to the south side. These peculiarities of design can be explained only by requirements of cult, and, though we do not know the specific arrangements, the building encompassed some sacred marks and tokens and artifacts of three deities: Athena Polias, Poseidon, and the hero Erechtheus.1 In the east section of the building, facing the Altar, was the very old olive-wood statue of Athena Polias herself. Adjoining the west end of the Erechtheum was a special precinct of Pandrosus, a daughter of Cecrops, and in this precinct grew the olive tree sacred to Athena, the symbol of her possession of and devotion to Athens.

The Great Altar, the Erechtheum, and the precinct with the sacred olive tree on the north side of the Acropolis made up the core of the cult of Athena Polias, the center of Athenian state cult in general. Much that concerned the mythology and cult of this complex, however, was represented in the sculpture of the Parthenon

Figure 4.3 View of Erechtheum from the south, with east façade of the cella and, to the west, the projecting Caryatid Porch. Built in the years 421–406 B.C.E. Photograph by the author.

on the south side of the Acropolis: on the east pediment the birth of Athena; on the west pediment the competition of Poseidon and Athena for patronage of Athens; and, on the frieze, the procession of the Panathenaea and the presentation of the sacred robe, the peplos, that was to be worn by the Athena Polias of the Erechtheum. This raises the question of the function of the Parthenon in this sanctuary complex. It, too, had a statue of Athena, the ten-meter tall gold and ivory Athena Parthenos (Virgin) sculpted by Phidias (Plate 2). The Parthenon also housed precious gold and silver dedications to Athena, and its west room served as the treasury of Athens. But, unlike the Erechtheum, it had no altar to its east nor did it shelter, like the Erechtheum, ancient marks or tokens of special religious reverence. Scholars have established, in fact, that Athena Parthenos was not a deity distinct from Athena Polias – she did not have, for example, her own priestess or altar – but that Parthenos was an added, descriptive (not functional) epithet for Athena Polias. That makes it most probable that the Parthenon was, as it were, a treasury building of the Athena Polias cult – one exceptionally large and beautiful, and possessing an exceptionally beautiful dedication in Phidias’ statue, but still, in terms of sanctuary design, more a building for storage than for worship. The cult

Figure 4.4 Plan of Erechtheum, with cella of Athena Polias to the east, Caryatid porch to the south, and the North Porch. To the west are the sanctuary of Pandrosus and the sacred olive tree of Athena.

that the Parthenon “supported,” both physically and by its sculpture, was that of Athena Polias with her Great Altar, Erechtheum, and sacred olive tree.

Now in turn Athene, daughter of Zeus of the aegis, beside the threshold of her father slipped off her elaborate dress which she herself had wrought with her hands’ patience, and now assuming the war tunic of Zeus who gathers the clouds, she armed in her gear for the dismal fighting. And across her shoulders she threw the betasselled, terrible aegis, all about which Terror hangs like a garland, and Hatred is there, and Battle Strength, and heart-freezing

Onslaught

and thereon is set the head of the grim gigantic Gorgon, a thing of fear and horror, portent of Zeus of the aegis. Upon her head she set the golden helm with its four sheets and two horns, wrought with the fighting men of a hundred cities. She set her feet in the blazing chariot and took up a spear heavy, huge, thick, wherewith she beats down the battalions

of fighting

men, against whom she of the mighty father is angered.

Homer, Iliad 5.733–47 (Lattimore translation)

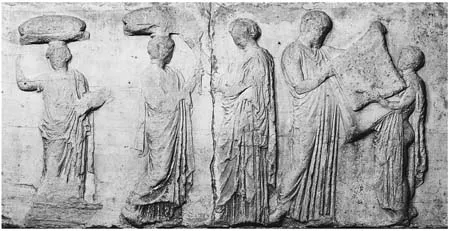

The statue of Athena Polias in the Erechtheum was probably life-sized and seated, of olive wood, and very ancient, so ancient and crudely shaped that some thought it had fallen from the sky, others that Cecrops or Erechtheus had had it made. She wore the saffron-colored peplos, a dress woven and decorated with scenes of the battle between the gods and the Giants. A new peplos was presented to her each year at the Panathenaea, and the presentation of the peplos is the central scene amidst the gathering of gods and ten heroes, perhaps Athens’ ten eponymous heroes, on the east frieze of the Parthenon.2 Athena Polias wore, in addition, a crown, earrings, a neckband, a gold owl, and an aegis with the image of the Gorgon. She held in one hand a type of bowl commonly

Figure 4.5 The peplos and how it was worn by Greek women. Drawing courtesy of Susan Bird.

Figure 4.6 This central scene of the east side of the Parthenon frieze apparently represents the presentation of Athena’s new peplos (folded, on right), a distinctive and core element of the Panathenaia, Athena’s major festival in Athens. The female figure (center right) may be the priestess of Athena, and the male figure to her right a state official, but the identity of all figures and of the objects represented are much disputed. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

used in offerings to the gods. The goddess might thus seem to be in domestic garb, but the aegis, a goatskin fringed with snakes and worn over her peplos and with the Gorgon’s head in the center, served as an almost magical breastplate. It was with the aegis that Athena armed herself for battle in the Iliad (5.733–47), and the similarity between the dress of Polias and the Athena of the Iliad is so great that one might be inclined to assume that the Athenians used Homer’s description to design the “clothing” for their most sacred statue.

Athena Promachos was the armed goddess facing the entrance of the Acropolis, known to the Athenians as the “bronze Athena.” She was a dedication from the victory over the Persians and was erected in the 450s. The ivory and gold Athena Parthenos was completed in 438 B.C.E. (Plate 2). Both were much more overtly militaristic than Polias herself. Both goddesses, monumental in size, were represented by Phidias as fully armed, with helmets, breastplates, spears, and with shields resting on the ground at their sides. Both are the warrior goddess “at ease, but vigilant.” The upright spear and helmet of Promachos could be seen from out at sea by those sailing into Piraeus harbor. The Parthenos held in her right hand a life-sized statue of a winged Nike (Victory). Inside her shield was coiled a large snake. In the Erechtheum the Athenians tended a real snake, perhaps embodying or symbolizing the hero Erechtheus, and, when the Persian attack on Athens was imminent in 480, the Athenians discovered that the food they left out each month for the snake had gone uneaten. They concluded that the goddess had evacuated the Acropolis and that they should take their statue of Athena Polias and do the same.

We may view both Athena Promachos and Athena Parthenos as monumental dedications to Athena Polias, and therefore in attempting to understand the cult of Athena on the Acropolis, we should focus our attention on Athena Polias. She, a goddess, was appropriately served by a priestess. Her first priestess may have been Cecrops’ daughter Aglaurus, and we saw in Myth #3 of Chapter III that Euripides had Athena herself name Erechtheus’ wife to be her priestess. In the historical period the priestess of Athena Polias was chosen from the family of the Eteobutadae, and the same family provided the priest for the cult of Poseidon-Erechtheus who was also, for reasons we saw in Myth #3 of Chapter III, worshiped in the Erechtheum. One old, aristocratic family thus provided the priest and priestess of this core state cult, and they would do so for centuries to come. The priest’s and priestess’ main duties were to make the prayers and offerings to their respective deities, and the priestess no doubt presented the peplos to Athena as one of the culminating acts of the Panathenaea. Athena Polias was also served each year by four girls aged 7–10, who, under adult supervision, wove and embroidered Athena’s peplos. Athena’s cult was also very wealthy, with hundreds of dedications, many of gold and silver, and with many precious statues. The gold of the Parthenos statue alone weighed about 1,000 kilos (Thucydides 2.13). During the prosperous times of the Athenian empire Athena received 1/60 of the tribute being paid by subject states, and Athena’s share of this tribute could amount to as much as ten talents ($6,000,000) in some years. To record, inventory, and account for these considerable as...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of color plates

- List of figures

- List of maps

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- I An Overview: Greek Sanctuaries and Worship

- II Greek Gods, Heroes, and Polytheism

- III Seven Greek Cult Myths

- IV Five Major Greek Cults

- V Religion in the Greek Family and Village

- VI Religion of the Greek City-State

- VII Greek Religion and the Individual

- VIII Greek Religion in the Hellenistic Period

- IX Greek Religion and Greek Culture

- Glossary of recurring Greek terms

- Index