- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

We are surrounded by polymers: Whether it's to prepare a meal, use computer keyboards and mousepads, or step onto a new playground,

you'll encounter a plastic product made of polymers. Owing to the extraordinary range of properties accessible in polymeric materials, they play an essential and ubiquitous role in everyday life - from plastics and elastomers on the one hand to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are essential for life on the other.

This desktop and library reference book provides a comprehensive yet concise overview of the materials, manufacture, structure and architecture, properties, processing, and applications of withing the field of polymers. The book offers a unique mix of theory and application,

the essential personal reference for anyone studying or working within the field of polymers.

you'll encounter a plastic product made of polymers. Owing to the extraordinary range of properties accessible in polymeric materials, they play an essential and ubiquitous role in everyday life - from plastics and elastomers on the one hand to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are essential for life on the other.

This desktop and library reference book provides a comprehensive yet concise overview of the materials, manufacture, structure and architecture, properties, processing, and applications of withing the field of polymers. The book offers a unique mix of theory and application,

the essential personal reference for anyone studying or working within the field of polymers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Polymers in Industry from A to Z by Leno Mascia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Chemical & Biochemical Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1I

1. Impact Modifier

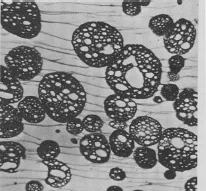

A general term for an auxiliary component of a polymer or resin formulation used to increase the toughness of products. In the case of thermoplastics, an impact modifier is incorporated into a brittle polymer matrix as pre-formed ‘toughening’ particles. The composition and morphology of the particles are designed in such a way as to promote strong interfacial bonds between the toughening particles and the surrounding polymer matrix, thus promoting an efficient stress transfer mechanism between the two phases. In this way the localized strain energy resulting from impacts can be redistributed through the bulk via the toughening particles, thereby preventing the formation and propagation of cracks. An example of this ‘toughening’ mechanism is the use of acrylic or ABS impact modifiers in rigid PVC formulations. There are, however, a number of theories that have been put forward for the toughening mechanism of polymers and, indeed, more than one mechanism can operate, depending on the nature of the polymer. For HIPS and ABS, for instance, it has been proposed that toughening takes place via the formation of crazes through the matrix between rubber particles, as a mechanism for absorbing the strain energy (see diagram).

Crazes formed between dispersed particles of a high-impact polystyrene sample. Source: Unidentified original source.

It is possible, however, that the formation of crazes represents a ‘second-stage’ event, which follows the energy absorption mechanism by molecular relaxation within the ‘interphase’ regions, consisting of miscible domains of the two components. For thermosetting resins, the particles that bring about the toughening of the matrix are generated in situ through the addition of specially designed oligomers that react with the resin and hardener. The rubbery particles are nucleated before ‘gelation’ of the resin takes place and grow into larger particles as a result of the migration of reactive species from the surrounding resin mixture. The growth of precipitated particles ceases when the surrounding matrix ‘gels’ through the formation of a continuous network. The infusion of reactive species, such as the hardener, from the surrounding resin into the precipitated particles may nucleate the formation of other particles, which remain quite small owing to the constraints imposed by hardening of the matrix surrounding the larger particle agglomerates. (See Epoxy resin and Phase inversion.)

2. Impact Strength

Denotes the resistance of a material to impact loads, normally expressed in terms of the energy required to induce fracture of specific specimens. In this respect the term ‘strength’ is a misnomer insofar as strength normally denotes the value of the stress (force per unit area) required to fracture a specimen. Impact strength is usually measured with the use of pendulum equipment or by falling-weight methods. (See Impact test, Fracture test and Fracture mechanics.)

3. Impact Test

Tests carried out by delivering loads at very high speed. (See Charpy impact strength, Izod impact test and Falling-weight impact test.)

4. Induction Time

A generic term used to denote the delay time for the start an event or process. Three specific examples of induction time experienced in polymer systems follow.

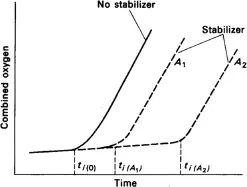

a. Degradation and stabilization The oxygen uptake of a polyolefin sample can be measured prior to reactions that lead to the formation of carbonyl groups in the chains, induced thermally or by the action of UV light. The efficiency of a stabilizer can, therefore, be assessed in terms of the increase in induction time that it brings about in a sample, as illustrated in the diagram.

Evolution of combined oxygen with ageing time.

b. Inhibition of polymerization The inhibition of polymerization or curing reactions by free radicals can be achieved using quinone. Very small amounts of inhibitor are added to an unsaturated monomer or oligomer to react with the initial free radicals by exposure to light and/or oxygen in order to convert them into inactive radicals. (See Antioxidant.) In this respect, inhibitors must be distinguished from retarders, which decrease the rate of reactions rather than increasing the induction time for the reaction to take place.

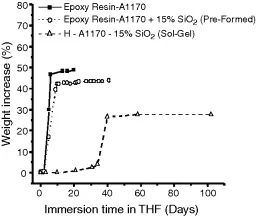

c. Liquid and gas absorption Solvent can be taken up by a glassy polymer sample via a case II diffusion mechanism. The diagram shows the absorption of tetrahydrofuran (THF) in three samples of ‘modified’ epoxy resin systems. The top two curves refer to a homogeneous glassy structure, the second relating to the same resin containing pre-formed silica particles. In both cases absorption takes place without an induction time. On the other hand, in the third sample, a distinct induction time and a large reduction in total amount of absorbed THF are observed. There, the silica was formed in situ as three-dimensional domains, which represents a typical structure of organic–inorganic hybrids. (See Organic–inorganic hybrid.)

Solvent uptake of an epoxy–silica hybrid. Source: Prezzi (2003).

5. Infrared Spectroscopy (IR or FTIR)

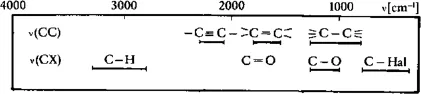

An analytical technique, known also as vibrational spectroscopy, used to identify specific chemical groups. The technique detects the transition between energy levels in molecules resulting from vibration of interatomic bonds within a chemical group. At low temperatures, molecules exist in their ground vibrational state. Therefore, in order to bring them to a higher energy state, it is necessary for them to absorb energy from the surroundings. In vibrational spectroscopy, this is done by subjecting a sample to electromagnetic (EM) radiation of a range of frequencies (a procedure known as scanning), and monitoring the intensity of the transmitted radiation. Chemical groups will absorb energy at specific frequencies through resonance with the natural vibrations of the constituent atomic bonds, so that they can be identified through a calibration procedure, which involves scanning a compound of known composition. For a standard IR analysis, the wavelength of the EM radiation is in the range 2.5–25 µm, corresponding to a frequency with wavenumber 4000–40 cm−1. (Note that the wavenumber in cm−1 is equal to 104/wavelength in µm.) The spectral position of the most common chemical groups in polymers that can be characterized by IR spectroscopy is indicated in the diagram.

Spectral position, as absorption wavenumber (cm−1), for (CC) and (CX) valency vibrations. Source: Kampf (1986).

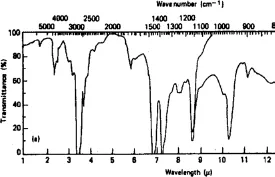

Some spectrometers operate in the near-infrared (NIR) region 0.7–2.5 µm (4000–1400 cm−1) and others in the far-infrared (FIR) region 50–800 µm (200–12 cm−1). A typical IR spectrum obtained from a polymer sample is shown.

Typical infrared spectrum of a polymer.

In order to speed up the calculations required to process the acquired data, a mathematical technique, known as Fourier transforms, is often used in the software. The technique is referred to as Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

6. Inhibitor

An additive used to reduce the susceptibility of reactive species, such as monomers and resin–hardener mixtures, to undergo polymerization reactions during storage. The function of an inhibitor is to react with an active radical to give products with much lower reactivity. A classical inhibitor for free-radical polymerization is benzoquinone. Although hydroquinone is often used as a monomer ‘stabilizer’, it relies on the presence of oxygen to be transformed into an inhibitor through oxidation to quinone. In effect, the inhibitor increases the induction time for the onset of propagation reactions.

7. Initiator

An additive that starts the reactions leading to polymerization or network formation in free-radical reaction systems. (See Free radical and Peroxide.)

8. Injection Blow Moulding

A moulding technique for the production of containers, consisting of two separate processes: respectively, the production of the ‘pre-form’ by injection moulding, and the subsequent ‘blowing’ operation into the final dimensions. This allows the blowing process to take p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Search Guide

- List of Acronyms

- Chapter A: Abrasion Resistance — Azeotropic Copolymerization

- Chapter B: Back-Flow — Butyl Rubber

- Chapter C: Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) — Cyanate Ester

- Chapter D: DABCO — Dynamic Vulcanization

- Chapter E: Effective Modulus — Eyring Equation

- Chapter F: Fabrication — Fusion Promoter

- Chapter G: Gate — Gutta Percha

- Chapter H: Halogenated Fire Retardant — Hyperbranched Polymer

- Chapter I: Impact Modifier — Izod Impact Test

- Chapter J: J integral — Joint

- Chapter K: K Value — Kneading

- Chapter L: Lamella — Lüder Lines

- Chapter M: M100 and M300 — Mylar

- Chapter N: Nafion — Nylon Screw

- Chapter O: Oil Absorption — Ozone

- Chapter P: Paint — Pyrolysis

- Chapter Q: Q Meter — Quinone Structure

- Chapter R: Rabinowitsch Equation — Rutile

- Chapter S: Sag — Syntactic Foam

- Chapter T: Tack — Tyre Construction

- Chapter U: Ubbelohde Viscometer — UV Stabilizer

- Chapter V: Vacuum Forming — Vulcanization

- Chapter W: Wall Slip — Work of Adhesion

- Chapter X: X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) — Xenon Arc Lamp

- Chapter Y: Y Calibration Factor — Young's Modulus

- Chapter Z: Z-Blade Mixer — Zisman Plot

- References