- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lipids and Cellular Membranes in Amyloid Diseases

About this book

Addressing one of the biggest riddles in current molecular cell biology, this ground-breaking monograph builds the case for the crucial involvement of lipids and membranes in the formation of amyloid deposits. Tying together recent knowledge from in vitro and in vivo studes, and built on a sound biophysical and biochemical foundation, this overview brings the reader up to date with current models of the interplay between membranes and amyloid formation.

Required reading for any researcher interested in amyloid formation and amyloid toxicity, and possible avenues for the prevention or treatment of neurodegenerative disorders.

From the contents:

* Interactions of Alpha-Synuclein with Lipids

* Interaction of hIAPP and its Precursors with Membranes

* Amyloid Polymorphisms: Structural Basis and Significance in Biology and Molecular Medicine

* The Role of Lipid Rafts in Alzheimer's Disease

* Alzheimer's Disease as a Membrane-Associated Enzymopathy of Beta-Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Secretases

* Impaired Regulation of Glutamate Receptor Channels and Signaling Molecules by Beta-Amyloid in Alzheimer's Disease

* Membrane Changes in BSE and Scrapie

* Experimental Approaches and Technical Challenges for Studying Amyloid-Membrane Interactions

and more

Required reading for any researcher interested in amyloid formation and amyloid toxicity, and possible avenues for the prevention or treatment of neurodegenerative disorders.

From the contents:

* Interactions of Alpha-Synuclein with Lipids

* Interaction of hIAPP and its Precursors with Membranes

* Amyloid Polymorphisms: Structural Basis and Significance in Biology and Molecular Medicine

* The Role of Lipid Rafts in Alzheimer's Disease

* Alzheimer's Disease as a Membrane-Associated Enzymopathy of Beta-Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Secretases

* Impaired Regulation of Glutamate Receptor Channels and Signaling Molecules by Beta-Amyloid in Alzheimer's Disease

* Membrane Changes in BSE and Scrapie

* Experimental Approaches and Technical Challenges for Studying Amyloid-Membrane Interactions

and more

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lipids and Cellular Membranes in Amyloid Diseases by Raz Jelinek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze biologiche & Biochimica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Interactions of α-Synuclein with Lipids and Artificial Membranes Monitored by ESIPT Probes

1.1 Introduction to Parkinson's Disease and α-Synuclein

Protein conformational disorders are a group of diseases associated with misfolding and pathological aggregation of one or more proteins, leading to impairment of functionality and sequestration into insoluble bodies [1]. In the case of the neurodegenerative diseases, the dominant character of certain genetic alterations indicates that a gain of toxic function in one or more stages of the aggregation process is required for clinical progression. Parkinson's disease (PD), the second most frequent neurodegenerative syndrome affecting >1% of the population above 60 years in age, is characterized by debilitating, progressive, and irreversible neuromotor degeneration and impaired cognitive functions. The classical symptoms include muscle rigidity, bradykinesia, akinesia, postural instability, and resting tremor arising from reduced dopamine secretion, secondary to the loss of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and other nuclei of the midbrain. As PD progresses, components of the autonomic, limbic, and somatomotor systems are affected, finally extending to the neocortex with development of the full-blown clinical picture [2–4].

Although drug-based therapies serve to palliate the symptomatology of PD, a specific curative treatment is as yet unavailable [2, 3, 5, 6]. PD remains incurable primarily because its etiology remains obscure [6]. Genetic factors, exposure to certain herbicides, and oxidative stress have been established as strong etiological components; other agents and factors are undoubtedly involved. Due to the multifactorial nature of PD, it is difficult, if not impossible, to ascribe specific functional alterations to a single protein, mechanism, or neuronal type. The “amyloid hypothesis” originally proposed that aberrant protein fibrillar aggregation compromises cellular functionality, ultimately leading to neurodegeneration [7]. However, intermediates (“oligomers”) of the aggregation pathway are currently considered as the more likely culprits in cellular toxicity [8], dysfunction, and death, rather than the large amyloid fibrillar aggregates, which instead may function as a protective sequestration mechanism. Among the genetic factors involved in PD, the (over)expression/mutation of α-synuclein (AS) is most prominently implicated in cytopathology [9]. Several genetic alterations in the SNCA gene (located in the PARK1 locus) are associated with the early onset familial dominant form of PD, and AS has been identified as the major component of Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites (LNs), amyloid aggregates found in the neuronal cell bodies and axons, respectively, of patients suffering from PD. LBs and LNs also include lower concentrations of distinctive lipids and other proteins. These amyloid deposits constitute the pathological hallmark in the brains of patients with synucleinopathies: PD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and multiple system atrophy (MSA).

Little is known about the biology of AS and its physiological functions remain obscure. It is found in high concentrations in the presynaptic nerve terminals associated with secretory vesicles, and also in glia, and it has been suggested that AS is involved in neurotransmitter secretion and reabsorption and in synaptic plasticity [10–15]. Nevertheless, SNCA knockout mice are viable, suggesting that AS is not essential either for neuronal development or for survival.

Point mutations (A30P, E46K, and A53T) and the more frequent gene duplication events are strongly correlated with early onset familial PD. Most affected individuals suffer from spontaneous PD, again indicating that a combination of genetic predisposition [16] and environmental factors is involved. Thus, at the molecular level, the physiological and aberrant interactions of AS with other biomolecules and organelles (e.g., catecholamines, membranes, mitochondria) and important influences of other external factors are at the focus of attention, with oxidative stress being of manifestly central relevance.

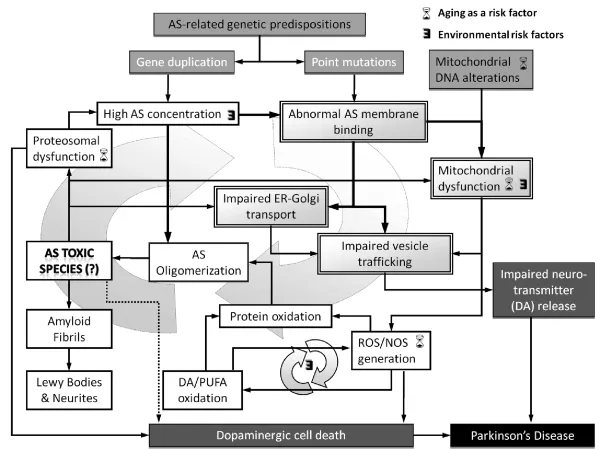

Lipids play a central role in PD pathology as important modulators of AS biology and protein–membrane interactions [3, 17, 18]. AS associates with secretory vesicles and the mitochondrial inner membrane [3, 17, 19]. The high affinity of AS for membranes implies that the latter not only mediate physiological protein localization but also may serve to initiate and/or modulate aberrant interactions and the rate of protein aggregation in the pathological context. Depending on the membrane composition (polar headgroups, acyl chain lengths and saturation, cholesterol content), lipids either accelerate [20–23] or inhibit [24, 25] AS fibrillation. Hence it is highly probable that preferential AS aggregation in the proximity of specific organelle membranes may account for the perturbation and dysfunction of certain cellular mechanisms (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Molecular and cellular processes related to AS and PD. PD is a multifactorial disease and neuronal dysfunction arises by the concurrent action of environmental factors stressing the functions of mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and proteasomes. Genetic predisposition (gene duplication and missense mutations of SNCA gene, mutations in other genes) is further exacerbated in dopaminergic cells by the susceptibility to the promoters of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen (NOS) species. Boxes with double borders indicate membrane participation in the indicated process.

It has been proposed that AS oligomers or low molecular weight aggregates are able to disrupt membranes and/or induce the formation of ion channels ([26–28]; see also Chapter 2), possibly leading to cellular and mitochondrial membrane depolarization [29]. Increased levels of AS can also block vesicular trafficking between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the Golgi complex [30], thereby affecting many cellular processes, including autophagic recycling of damaged mitochondria. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to oxidative stress and thus to augmented AS aggregation promoted by protein oxidation. This process may constitute a cyclic mechanism for progressive toxicity [17] that is further exacerbated by the presence of dopamine (DA) and related metabolites in specialized neuronal cells (Figure 1.1).

AS binds fatty acids (FAs), presumably via the hydrophobic core of the NAC (non-Aβ component) region, and the bound FAs modulate aggregation of the protein [31–33]. Particularly active are the long- and very long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that are abundant in the central nervous system [34]. Arachidonic acid, for example, facilitates AS oligomerization when present in membrane vesicles or free in solution [22], and FAs, such as oleic acid, trigger AS aggregation in vitro [35]. Whereas PUFAs stabilize some kinds of soluble oligomeric and toxic species, saturated FAs inhibit their formation [36, 37]. Furthermore, the high sensitivity of PUFA- and DA-related metabolites to oxidative stress supports the notion that a combination of multifactorial alterations may converge in dopaminergic cells to trigger and promote AS toxicity, even in the absence of genetic predisposition factors. AS has also been implicated in the regulation of inflammatory response in the brain by sequestration of precursors (arachidonic acid) for prostanoids and reduction of proinflammatory cytokine secretion [38]. These factors are also known to be important for PD progression and probably for its onset.

Due to the lack of an effective PD therapy, basic research on the biology and the role of lipids in synucleinopathies is essential for understanding the etiology of neurodegenerative diseases and for the identification of potential drug targets. The classical functions attributed to lipids are energy storage and definition of physical barriers. Hence they serve as substrates for organizing the structure of biological membranes, both defining and isolating internal compartments and also providing the interface of the cell with its external milieu. Lipids function in a majority of cellular processes, ranging from protein targeting to signaling by hormones and second messengers. These phenomena are at the focus of this chapter, particularly in relation to the pathological processes involving amyloidogenic proteins.

1.2 Structural Biology of α-Synuclein

AS is a 140 amino acid polypeptide of 14.5 kDa with three distinguishable domains: the N-terminal, the NAC, and the C-terminal regions (Figure 1.2). AS migrates as a 20–30 kDa protein in size-exclusion columns due to the lack of a classical secondary structure when free in solution [39, 40]. As such, AS is assigned to the family of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), characterized by an unconventional energy landscape lacking the classical “folding funnel” and occupying instead a broad conformational space with no clear minimum (native folding structure) [41, 42]. However, it has been proposed that monomeric AS in solution adopts transient and variable conformations, for example, ring-shaped, that can rationalize some of the experimental structural data [40, 43, 44]. According to this model, the C-terminal acidic region is folded over the partially positive N-terminal region and stabilized primarily by long-range electrostatic interactions. This orientation shields the NAC region, which is rich in hydrophobic residues and constitutes the core for protein aggregation [45]. Compounds such as polyamines and cations that bind to the C-terminus and thereby disrupt the fold-back structure promote AS aggregation [43, 46].

Figure 1.2 AS primary and secondary structures. AS contains seven imperfect repeats of 11-mer residues in the first two-thirds of its sequence, which are thought to be important in forming the lipid-bound α-helical and for the amyloid cross-β-sheet structures, whereas the highly acidic C-terminal region remains in a disordered state. Triangles and hollow arrows indicate the positions of Cys and familial mutants, respectively. The β-sheet regions are shown schematically; f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Further Reading

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1: Interactions of α-Synuclein with Lipids and Artificial Membranes Monitored by ESIPT Probes

- Chapter 2: Structural and Functional Insights into a–Synuclein–Lipid Interactions

- Chapter 3: Surfactants and Alcohols as Inducers of Protein Amyloid: Aggregation Chaperones or Membrane Simulators?

- Chapter 4: Interaction of hIAPP and Its Precursors with Model and Biological Membranes

- Chapter 5: Amyloid Polymorphisms: Structural Basis and Significance in Biology and Molecular Medicine

- Chapter 6: Intracellular Amyloid ß: a Modification to the Amyloid Hypothesis in Alzheimer's Disease

- Chapter 7: Lipid Rafts Play a Crucial Role in Protein Interactions and Intracellular Signaling Involved in Neuronal Preservation Against Alzheimer's Disease

- Chapter 8: Alzheimer's Disease as a Membrane-Associated Enzymopathy of ß-Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Secretases

- Chapter 9: Impaired Regulation of Glutamate Receptor Channels and Signaling Molecules by ß-Amyloid in Alzheimer's Disease

- Chapter 10: Membrane Changes in BSE and Scrapie

- Chapter 11: Interaction of Alzheimer Amyloid Peptide with Cell Surfaces and Artificial Membranes

- Chapter 12: Experimental Approaches and Technical Challenges for Studying Amyloid–Membrane Interactions

- Index