![]()

CHAPTER 1

How Credit Slipped Its Leash

Irredeemable paper money has almost invariably proved a curse to the country employing it.

—Irving Fisher1

Credit-induced boom and bust cycles are not new. What makes this one so extraordinary is the magnitude of the credit expansion that fed it. Throughout most of the twentieth century, two important constraints limited how much credit could be created in the United States. The legal requirement that the Federal Reserve hold gold to back the paper currency it issued was the first. The legal requirement that commercial banks hold liquidity reserves to back their deposits was the second. This chapter describes how those constraints were removed, allowing credit to expand to an extent that economists of earlier generations would have found inconceivable.

Opening Pandora’s Box

In February 1968, President Lyndon Johnson asked Congress to end the requirement that dollars be backed by gold. He said:

The following month Congress complied.

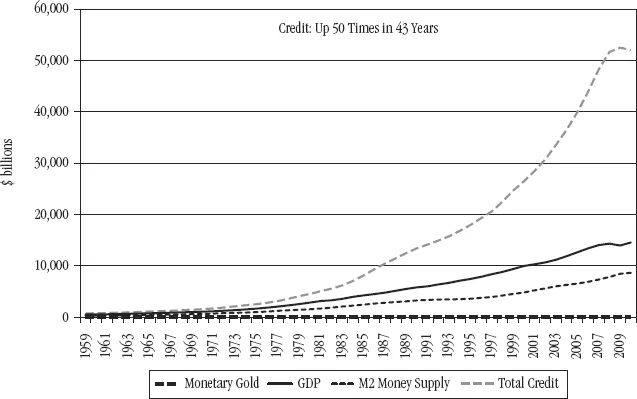

That decision fundamentally altered the nature of money in the United States and permitted an unprecedented proliferation of credit. Exhibit 1.1 dramatically illustrates what has occurred.

The monetary gold line at the bottom of the chart represents the gold held within the banking system. It peaked at $19 billion in 1959 and afterward contracted to $10 billion by 1971. M2 represents the money supply as defined as currency held by the public, bank liquidity reserves, and deposits at commercial banks. The top line represents total credit in the country.

It is immediately apparent that credit expanded dramatically both in absolute terms and relative to gold in the banking system and to the money supply. In 1968, the ratio of credit to gold was 128 times and the ratio of credit to the money supply was 2.4 times. By 2007, those ratios had expanded to more than 4,000 times and 6.6 times, respectively. Notice, also, the extraordinary expansion of the ratio of credit to GDP. In 1968, credit exceeded GDP by 1.5 times. In 2007, the amount of credit in the economy had grown to 3.4 times total economic output.

Total credit in the United States surpassed $1 trillion for the first time in 1964. Over the following 43 years, it increased 50 times to $50 trillion in 2007. That explosion of credit changed the world.

Constraints on the Fed and on Paper Money Creation

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 created the Federal Reserve System and gave it the power to issue Federal Reserve Notes (i.e., paper currency). However, that Act required the Fed to hold “reserves in gold of not less than forty per centum against its Federal Reserve notes in actual circulation.”3 In other words, the central bank was required to hold 40 cents worth of gold for each paper dollar it issued. In 1945, Congress reduced that ratio from 40 percent to 25 percent.

So much gold had flowed into U.S. banks during the second half of the 1930s as the result of political instability in Europe that the Federal Reserve had no difficulty meeting the required ratio of gold to currency for decades. In fact, in 1949, it held nearly enough gold to fully back every Federal Reserve note in circulation.

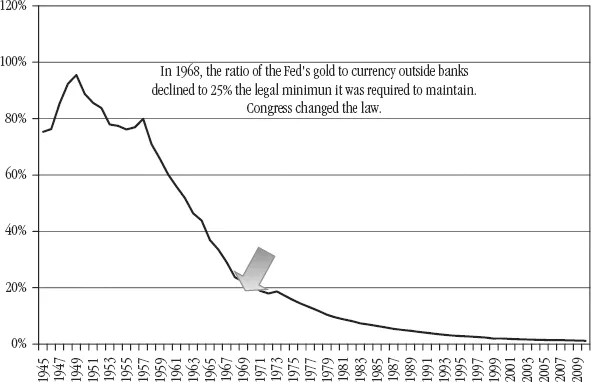

During the 1950s and 1960s, however, the amount of gold held by the Fed declined. From a peak of $24.4 billion in 1949, the Fed’s gold holdings fell to $19.4 billion in 1959 and to only $10.3 billion in 1968. Moreover, not only was the gold stock contracting, the currency in circulating was increasing at a significantly faster pace. During the 1950s, currency in circulation grew at an average rate of 1.5 percent a year, but by an average of 4.7 percent a year during the 1960s.

In 1968, the ratio of the Fed’s gold to currency in circulation declined to 25 percent (as shown in Exhibit 1.2), the level it was required to maintain by law. At that point, Congress, at the urging of President Johnson, removed that binding constraint entirely with the passage of the Gold Reserve Requirement Elimination Act of 1968. Afterward, the Fed was no longer required to hold any gold to back its Federal Reserve notes. Had the law not changed, either the Fed would have had to stop issuing new paper currency or else it would have had to acquire more gold.

Once dollars were no longer backed by gold, the nature of money changed. The worth of the currency in circulation was no longer derived from a real asset with intrinsic value. In other words, it was no longer commodity money. It had become fiat money—that is, it was money only because the government said it was money. There was no constraint on how much money of this kind the government could create. And, in the years that followed, the fiat money supply exploded.

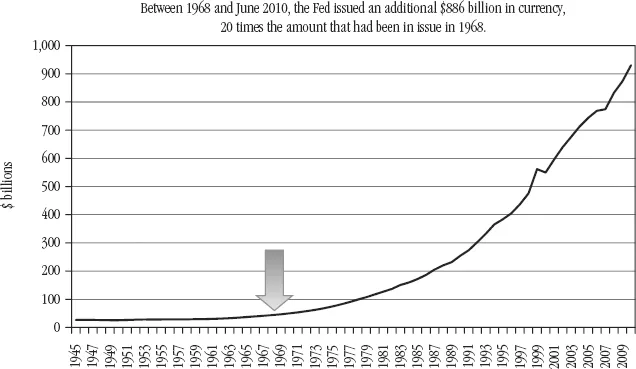

Between 1968 and 2010, the Fed increased the number of these paper dollars in circulation by 20 times by printing $886 billion worth of new Federal Reserve notes. (See Exhibit 1.3.) (Its gold holdings now amount to the equivalent of 1 percent of the Federal Reserves notes in circulation.)

Although this new paper money was no longer backed by gold (or by anything at all), it still served as the foundation upon which new credit could be created by the banking system. Fifty trillion dollars worth of credit could not have been erected on the 1968 base of 44 billion gold-backed dollars.

Fractional Reserve Banking Run Amok

The other constraint on credit creation at the time the Federal Reserve was established was the requirement that banks hold reserves to ensure they would have sufficient liquidity to repay their customers’ deposits on demand. The Federal Reserve Act specified that banks must hold such reserves either in their own vaults or else as deposits at the Federal Reserve.

The global economic crisis came about because, over time, regulators lowered the amount of reserves the financial system was required to hold until they were so small that they provided next to no constraint on the amount of credit the system could create. The money multiplier expanded toward infinity. A proliferation of credit created an economic boom that transformed not only the size and composition of the U.S. economy but also the size and composition of the global economy. The collapse came when the borrowers became too heavily indebted to repay what they had borrowed.

By 2007, the reserves ratio of the financial system as a whole had become so small that the amount of credit that the system created was far beyond anything the world had experienced before. By the turn of the century, the reserve requirement played practically no role whatsoever in constraining credit creation. This came about due to two changes in the regulation of the financial industry. The first was a reduction of the amount of reserves that banks were required to hold. The second was regulatory approval that allowed new types of creditors to enter the industry with little to no mandatory reserve requirements whatsoever. The following pages describe this evolution of the U.S. financial industry.

In order to understand how reserve requirements limited credit creation, it is first necessary to understand how credit is created through Fractional Reserve Banking.

Fractional Reserve Banking

Most banks around the world accept deposits, set aside a part of those deposits as reserves, and lend out the rest. Banks ho...