![]()

1

Single-screw Extrusion: Principles

Keith Luker

Randcastle Extrusion Systems, Inc.

1.1 Introduction

Until recently, single-screw extruders (SSE) have little changed in principle since their invention around 1897. They are mechanically simple devices. A one-piece screw, continuously rotated within a barrel, develops a good quality melt and generates high stable pressures for consistent output. These inherent characteristics, combined with low cost and low maintenance, make it the machine of choice for the production of virtually all extruded products.

Historically, the polymers and particulate they carry (including active pharmaceutical ingredients or API) are subjected to compressive shear-dominated deformation. Compression of particulates, such as API, forces the particulate together into agglomerations under very high pressure before and during melting. When this happens, shear deformation is insufficient to break the agglomerations into their constituent parts. Agglomerations within a polymer matrix define a poorly mixed product.

Many ingenious schemes are known to improve the basic screw. Since the 1950s, a variety of mixers have been available. Some of these force material into small spaces for additional shearing. Some divide the flow into many streams so that smaller masses are sheared more effectively. Some make use of pins embedded in the root of the screw and some cut the screw flights. They have one thing in common that limits their effectiveness, however: they are placed after the screw melts the material, and most of a screw is necessarily dedicated to producing a melted polymer. Typically, these mixers are less than four screw diameters long.

Since around the 1970s, various barrier or melt separation screws became widely available. These force material over a barrier flight of reduced dimension (compared to the main flight), preventing unmelted material from moving downstream. As the material moves over the barrier flight, it receives additional shearing and is therefore mixed a little bit better. Some screws force material back and forth across barriers which also slightly improves the SSE mixing.

To some degree, all of these inventions are incrementally successful. However, they do not change the fundamentals of compression and shear dominance in the SSE. Until recently, the SSE was therefore an agglomerating machine.

Meanwhile, the twin-screw extruder (TSE), and in particular the parallel intermeshing co-rotating TSE1, became the dominant continuous compounding mixer for polymers and particulate. This is because it works on a fundamentally different and better principle: It melts prior to the final compression of the melt. This means that it prevents agglomeration of the ingredients and has no need to then break up agglomerates formed by compression. Fundamentally, it is not shear dominated. Instead, material moving through the intersection of the screws is extended. Such deformation is elongational. Elongation, instead of pushing API particles together, pulls them apart. Unlike the SSEs discussed above, the TSE mixers do not start mixing near the end of the screw. They do not dedicate just a few length-over-diameter or L/D ratios to mixing; instead, they combine elongational melting and mixing early in the extruder in a first set of kneaders and then repeat the elongational melt-mixing process with additional kneaders. In this way, a substantial part of the TSE length is dedicated to elongational melt-mixing.

However, the TSE has flaws. Not all the material moves through the intermesh region; some material escapes down the channels without moving through the extensional fields. In addition, some material will see the intermesh many times. The key elongational history of the polymer and API will therefore be uneven. Compared to single screws, the TSE is less pressure stable; compared to singles, the TSE does not generate high pressures. (When a gear pump is used to generate high stable pressures they require a sophisticated algorithm that is sensitive to small changes, especially in the starve feeding system.)

Very recently, significant advances in fundamental SSE technology have changed the landscape. Costeux et al. proved in 2011 [1] that the SSE could have dominant elongational flow where melting occurred before compression. There is therefore no need to break up agglomerates. Unlike the TSE, all the material can consistently pass through the elongational mixers. Melting and mixing are started very near the hopper so that a significant part of the total length of the SSE becomes a mixer. These new SSEs retain their advantages of simplicity and low cost. They can still generate high and stable pressures most suitable for hot-melt extrusion (HME) production, even when starve fed without a complex control system.

1.2 Ideal Compounding

In order to understand the SSE for HME, we must understand compounding as we will necessarily have at least an API and a polymer. It is undesirable to have local concentrations of API or polymer in the product. Compounding is defined as combining two or more ingredients, but really good compounding has additional requirements. The melt-mixing process should treat the material equally. It should not be overly mixed in one region and under-mixed in another. Mixing should apply the least amount of energy to limit degradation of the components.

Compounding is accomplished by taking local concentrations and reducing them to a satisfactory size where satisfaction depends on the use. This is accomplished by dispersion (breaking solids or globules into smaller concentrations) or distribution (rearrangement of solids or melt).

Local concentrations will occur when polymer pellets are dry-mixed with API. Each pellet is a local concentration that must be distributed to incorporate the API. The API can also be thought of as a local concentration that must be distributed within the polymer pellets. Local concentrations are immediately reduced when working with a powder/powder blend (compared to pellet/powder). The better the mixture, the easier it is for an extruder to further reduce the local concentrations. Nevertheless, no matter how well mixed two powders are, there will be local concentrations at some scale. The job of the extruder is to further reduce these concentrations. This cannot be accomplished through a purely compressive screw since that takes the mixture and, at best, maintains the dry-mix quality2. Instead, elongation is required to draw the concentrated regions apart.

An ideal HME mixer would maintain ingredient quality during the compounding process. Both plastics and API degrade due to thermal and mechanical stress. To mix well, there should be an orderly progression through the mixing process that maintains the quality of the ingredients.

Thermally, a single heat history of the shortest possible duration at the lowest temperature is preferred.

Mechanically, an elongationally dominated system, where all the material has the same elongational history, is preferred. This will minimize unnecessary mechanical degradation and decrease the thermal processing time to achieve the same result. Since the shear component of the mechanical system builds excessive heat (compared to the elongational component), it should be minimized.

1.3 Basics of the Single-screw Extruder

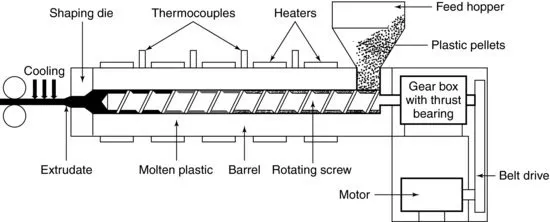

Low bulk density polymer solids, often mixed with various forms of particulate (such as API), most commonly fall from a hopper into a long, continuously rotated extruder screw within a temperature controlled barrel, as depicted in Figure 1.1.

The screw forces the solid material into a decreasing space along the screw at higher temperatures. There the compressed material is pushed up against the heated container (the barrel). The compression both forces the air out of the hopper and melts the material by pushing the material against the hot metal barrel. The dense/molten material is continuously pumped forward through a shaping die. The material exits the die where it is drawn down in a free molten state through a cooling medium until solid while continually pulled.

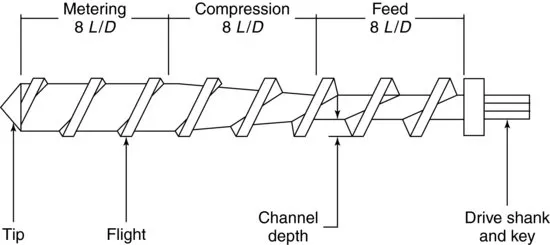

The key to the process is the extruder screw. While many variations can be considered, the classic screw has a constant diameter. The modern screw length is usually 24–50 times its diameter. This is expressed as the length-over-diameter ratio or L/D ratio. Screws are, most commonly, made from a solid piece of steel leaving a screw root that is polished. The flights are ground and fit closely within the barrel. Figure 1.2 depicts a general-purpose polymer 24/1 L/D screw.

Typically, the one-piece screw is driven from the right through a simple key on a ...