![]()

Part 1: Setting the Scene

EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION

Rather than being just concerned and conservative about remains of ‘wild nature’, ecological restoration requires a dynamic, adaptive approach to problem solving and resource management, especially in this era of rapid and irreversible change in climate, land use and species assemblages. Indeed, evolutionary and environmental dynamics, such as invasions of species outside their recent biographical ranges, and anthropogenic climate change, can no longer be denied or ignored, as was often the case when ecological restoration was associated solely with nature conservation concerns. However, as we think about potential future developments in ecological restoration, we must respect the historic roots of our human societies, and the relationship between them and nonhuman nature as well. Evolution of species has been a natural phenomenon throughout the history of life on Earth, but the direction and speed for some species have been strongly influenced by human activities, such as plant and animal breeding, and also indirectly affected by our growing impact on global, regional and local environments. Similarly, climate change has been a natural phenomenon since the very beginning of the Earth’s existence, but the recent rate of change is recognized by all experts as being largely due to human impact. This is one of the main reasons why humanity must accept responsibility for its actions, and include nature management in the decision-making process of planning towards a sustainable and desirable future – especially as we climb from the current 7 billion people to an estimated 9–10 billion in the next 25 years.

Not only does nature alter in response to changes in environmental conditions, but also human societies change and adapt to new conditions. Wilderness, earlier considered as areas to be exploited for human well-being, is nowadays valued as near-natural ecosystems to be cherished and protected. Similarly, what was earlier considered as ‘wastelands’ may now be called seminatural ecosystems; if financing is provided, even derelict and devastated post-mining areas may effectively be revegetated, rehabilitated and ‘recycled’ into the mainstream of society. However, for ecological restoration to be successful, a firm agreement is required between all the stakeholders. Opportunities have to be valued in terms of scientific validation, societal needs and available budgets for execution and monitoring.

We start our book by giving a brief overview of changing points of view on nature and on the goals of nature management, along with changes in the human society (Chapter 1). In brief, this implies a change from human dependence on nature towards nature’s dependence on human management. In Chapter 2, we present some of the key concepts in the field of restoration ecology where for example we explain how to distinguish between the reintegration of disrupted and dysfunctional landscapes, the restoration of degraded ecosystems, and the rescue of biodiversity through the reinforcement or reintroduction of species populations. We also discuss such concepts as stability, the functional role of biodiversity, reference systems and how stocks of natural capital allow the flow of ecosystem services. However, we note that despite recent progress huge uncertainties and unknowns remain in our field.

In Chapter 3, our colleague Richard Hobbs pays explicit attention to this problem, helping the reader focus on the challenge of coping with ongoing changes in climate even as we set about the restoration of degraded ecosystems in the context of highly modified landscapes. Indeed, an intriguing and important question is to what extent historical knowledge and perspective can continue to be applicable if we are restoring now ‘towards the future’, as we put it in the preface. Finally, David Tongway and John Ludwig describe an approach to landscape-scale restoration that emphasizes the need for understanding how ecosystem processes are affected by disturbances, causing landscapes to be dysfunctional (Chapter 4). This knowledge can then be used by practitioners to set achievable goals, and to design and implement restoration technologies to achieve their goals.

In summary, this first part of our book sets the scene for all that follows. Rather than giving a complete overview, we aim at highlighting topics that we consider to be necessary elements for the reader who will here discover the rapidly growing, and evolving, field of restoration ecology; we hope it will give you an appetite to carry on reading the book and at least some of the references cited and, above all, to start thinking about concepts and strategies for differing biophysical and sociocultural contexts where ecological restoration is needed.

![]()

Chapter 1

Getting Started

Jelte van Andel and James Aronson

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Increasing and unrelenting human impact on the biosphere – in particular since the industrial revolution began in the late eighteenth century – has brought us to the threshold of what Paul Crutzen dubbed the ‘Anthropocene Era’, that is an unprecedented geological era in which humans dominate all ecosystems and the global environment as a whole. However, the widespread recognition of the need to regulate the human ‘footprint’ dates back only a few decades, in most parts of the world. Pioneer nature conservation organizations began to be formed over a century ago, it is true, in western and central Europe in particular – including the German Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union, founded in 1899, and the Dutch organization known as Natuurmonumenten that was founded by an elementary school teacher in Amsterdam in 1905. Today, there are literally thousands of conservation NGOs around the world, and gradually, over the past 50 years, they have found increasing support from the public and the scientific community. Although started as recently as the 1960s, ‘in response to the devastation of our natural habitats’, the network of Wildlife Trusts in the United Kingdom now has more than 800 000 members. This is just one example among many, and ecological restoration – under many different names – is gaining an increasing share of attention in conservation activities all around the world, and in international treaties as well.

In this introductory chapter, we start using the terminology related to the subject without defining the terms; the definitions will be given and discussed in the next chapter. Throughout the book we draw the reader’s attention to the Glossary in this book by marking terms in bold.

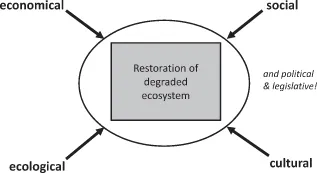

Restoration ecology is the field of study and experimentation that provides the scientific background and underpinnings for practical ecological restoration, rooted in the early developments and visionary work of a few individuals and programmes in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It has grown to a respectable ‘size’ and volume only in the last few decades, since Bradshaw’s (1983) pioneering work, but as mentioned already, is now gaining momentum and attention as never before. Restoration ecology has also begun to command much more attention from scientists in the last 25–30 years, especially since the Society for Ecological Restoration has got underway in the late 1980s. Twelve years ago, ecologist Truman Young suggested that ‘restoration ecology is the future of conservation biology’ (Young 2000). By that he surely meant that in today’s crowded, much-transformed world, conservation – in the sense of preservation or setting-aside – will not be adequate to meet the goals of conservation – and sustainability. Instead, restoration of damage will be required on both scores. In terms of the sciences, at any rate, a clear convergence between the three fields is taking place, conservation biology, restoration ecology and the overarching, inter- and transdisciplinary field of sustainability science that is barely a decade old. Why include the latter in this introductory chapter? Because ecological restoration does not only aim at the repair of degenerated ecosystems, including their structure and functioning and their biodiversity. For ecological restoration to be effective, we must consider not only the biophysical context, but also the socio-economic and political matrix in which a restoration project must be planned, financed and carried out. That is why there is a clear need for a broader interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity as well, which means forging interprofessional partnerships and coalitions, as well as good communication and indeed collaboration with nonprofessional stakeholders and neighbours. Jackson et al. (1995) portrayed ecological restoration as having four main components to consider – ecological, social, cultural and economic (see Figure 1.1). In the last few years, however, it is also becoming clear that political and legislative components are needed as well (Aronson 2010) and will also be an important part of restoration in coming years.

Ecological restoration aims at the safeguarding and the repair of what is commonly called ‘nature’ (i.e. ecosystems and biodiversity) and what ecological economists, and a growing number of ecologists, call humanity’s stock of natural capital (i.e. renewable and nonrenewable resources from ‘nature’) that assure the flow of ecosystem goods and services to society (Aronson et al. 2007a). Thus, many motivations and justifications for ecological restoration exist (see Clewell & Aronson 2006, and Chapter 2), yet a financial – and perhaps also a social or political – cost is inevitably involved. Increasingly, it is obvious – at least to us – that all societies everywhere should be devoting resources to this activity to insure and enhance the supply of ecosystem services as well. However, what may seem like a clear gain for some, can be perceived as a loss or waste of resources for others. Trade-offs, negotiation and, above all, good communication are a sine qua non in this realm of human endeavour that require both ecological and environmental as well as socio-economic and even political criteria for monitoring and evaluation (Blignaut et al. 2007; Aronson 2010).

Needless to say, points of view in most situations will differ among stakeholders, and they will also change over time, in any heterogeneous society, and even among specialized scientists. To illustrate this, let us consider the concept of steady states and disturbance, a key notion in all discussions of conservation, management and restoration of ecosystems.

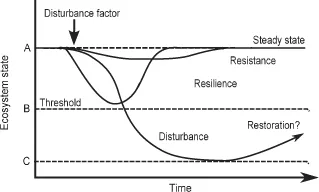

1.2 VIEWS ON STEADY STATES AND DISTURBANCE

Disturbance, though it may sound negative, is basically a neutral term in science. The term is widely used in ecology, and we will also use it in this book, but the neutral term ‘transformation’ is often a better choice for indicating a change of a complex system from one state to another one. What we call a disturbance factor causes a change or transformation in an ecosystem’s steady state, in terms of its standing biomass, productivity or biodiversity, which may be followed by either recovery to the former state (through resilience or resistance) or a change to another state, following the crossing of a so-called threshold of irreversibility (see Figure 1.2); then the system is disturbed. In the latter case, the system may shift to another steady state, or not; in the ecological literature, this new state is referred to as an alternative stable state.

Depending on your point of view, State C, the alternative steady state, can be a gain or improvement, or else a loss or example of degradation. For example, if a farmer clears a piece of woodland and then cultivates the land, he or she will naturally consider the change as a gain. Yet, from the point of view of a bird watcher, or local authority in charge of nature conservation, such a transformation may be considered as a loss of habitat for birds, or a degradation of the woodland ecosystem at the landscape scale. Similarly, local communities dependent on woodlands for various services (for example watershed protection and outdoor recreation) will consider it as negatively impacting their welfare and well-being. Thus, especially if the farmer eventually abandons production, for reasons of changing markets for example, there may be a good argument that ecological restoration should be attempted, in order to restore the woodland that once was there. However, the farmer may instead seek other crops or land uses that raise income to his or her family or corporation. In Chapter 2, we will return to the concept of disturbance, and the related one of stability. Here we will consider points of view on ‘nature’ as related to the qualification of ‘disturbance’.

1.3 VIEWS ON NATURE AND NATURE CONSERVATION

Just as views on what constitutes a disturbance differ, the same is true for notions of ‘nature’, ‘nature conservation’ and ‘ecological restoration’, and points of view may even change over time. In large parts of northern and central Europe and indeed the entire northern hemisphere, the forests and woodlands that developed after the last Ice Age ended, approximately 11 000 years ago, have repeatedly been exploited or even clear-cut for timber, and the lands they formerly occupied cleared and burnt to make way for agricultural production systems. Though this disturbance, or transformation, from forest or woodland to farmland and past...