![]()

Chapter 1

Human and Microbial World

1.1. Prologue

The microbial world is vast, diverse, and dynamic. The Earth hosts over 1030 microorganisms, representing the largest component of the planet's biomass. Microbes include bacteria, archaea, mollicutes, fungi, microalgae, viruses, and protozoa, and many more organisms with a wide range of morphologies and lifestyles. All other life-forms depend on microbial metabolic activity. Microorganisms have colonized virtually every environment on earth ranging from deep sea thermal vents, polar sea ice, desert rocks, guts of termites, roots of plants, to the human body. Much as we might like to ignore them, microbes are present everywhere in our bodies, living in our mouth, skin, lungs, and gut. Indeed, the human body has 10 times as many microbial cells as human cells. They are a vital part of our health, breaking down otherwise indigestible foods, making essential vitamins, and even shaping our immune system. While microbes are often feared for the diseases they may cause, other microorganisms mediate the essential biogeochemical cycles of key elements that make our planet habitable. Ancient lineages of microorganisms may hold the key to understanding the earliest history of life on earth.

1.2. Innovations in Microbiology for Human Welfare

The human society is overburdened with infectious diseases. Despite worldwide efforts toward prevention and cure of these deadly infections, they remain major causes of human morbidity and mortality. Microbes play a role in diseases such as ulcers, heart disease, and obesity. Over the past century, microbiologists have searched for more rapid and efficient means of microbial identification. The identification and differentiation of microorganisms has principally relied on microbial morphology and growth variables. Advances in molecular biology over the past few years have opened new avenues for microbial identification, characterization, and molecular approaches for studying various aspects of infectious diseases. Perhaps, the most important development has been the concerted efforts to determine the genome sequence of important human pathogens. The genome sequence of the pathogen provides us with the complete list of genes, and, through functional genomics, a potential list of novel drug targets and vaccine candidates can be identified (Hasnain, 2001). The genetic variation inherent in the human population can modulate success of any vaccine or chemotherapeutic agent. This is why, the sequencing of the human genome has attracted not only the interest of all those working on human genetic disorders but also the interest of scientists working in the field of infectious diseases.

1.2.1. Impact of Microbes on the Human Genome Project

Technology and resources generated by the Human Genome Project and other genomic research are already having a major impact on research across life sciences. The elucidation of the human genome sequence will have a tremendous impact on our understanding of the prevention and cure of infectious diseases. The human genome sequence will further advance our understanding of microbial pathogens and commensals and vice versa (Relman and Falkow, 2001). This will be possible through efforts in areas such as structural genomics, pharmacogenomics, comparative genomics, proteomics, and, most importantly, functional genomics. Functional genomics includes not only understanding the function of genes and other parts of the genome but also the organization and control of genetic pathway(s). There is an urgent need to apply high throughput methodologies such as microarrays, proteomics (the complete protein profile of a cell as a function of time and space), and study of single nucleotide polymorphisms, transgenes and gene knockouts. Microarrays have a tremendous potential in

1. Determining new gene loci in diseases

2. Understanding global cellular response to a particular mode of therapy

3. Elucidating changes in global gene expression profiles during disease conditions; and so on.

Increasingly detailed genome maps have aided researchers seeking genes associated with dozens of genetic conditions, including myotonic dystrophy, fragile X syndrome, neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2, inherited colon cancer, Alzheimer's disease, and familial breast cancer.

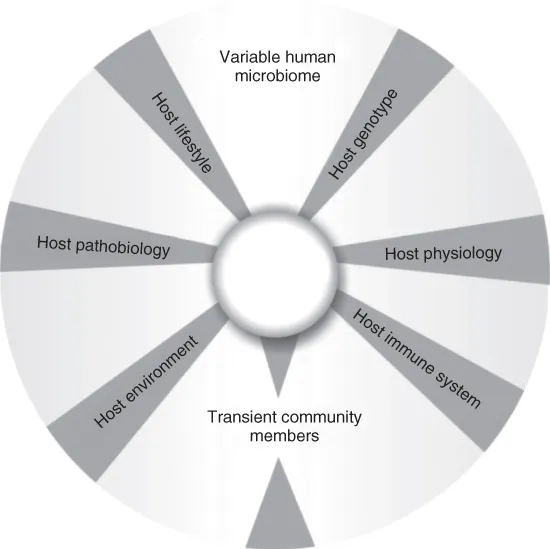

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) has published an analysis of 178 genomes from microbes that live in or on the human body. The core human microbiome is the set of genes present in a given habitat in all or the vast majority of humans (Fig. 1.1). The variable human microbiome is the set of genes present in a given habitat in a smaller subset of humans. This variation could result from a combination of factors such as host genotype, host physiological status (including the properties of the innate and adaptive immune systems), host pathobiology (disease status), host lifestyle (including diet), host environment (at home and/or work), and the presence of transient populations of microorganisms that cannot persistently colonize a habitat. The gradation in color of the core indicates the possibility that, during human microevolution, new genes might be included in the core microbiome, whereas other genes might be excluded (Turnbaugh et al., 2007). The researchers discovered novel genes and proteins that serve functions in human health and disease, adding a new level of understanding to what is known about the complexity and diversity of these organisms (http://www.nih.gov). Currently, only some of the bacteria, fungi, and viruses can grow in a laboratory setting. However, new genomic techniques can identify minute amounts of microbial DNA in an individual and determine its identity by comparing the genetic signature with known sequences in the project's database. Launched in 2008 as part of the NIH Common Fund's Roadmap for Medical Research, the HMP is a $157 million, five-year effort that will implement a series of increasingly complicated studies that reveal the interactive role of the microbiome in human health (http://www.eurekalert.org). The generated data will then be used to characterize the microbial communities found in samples taken from healthy human volunteers and, later, those with specific illnesses.

Studies were also conducted to evaluate the microbial diversity present in the HMP reference collection. For example, they found 29,693 previously undiscovered, unique proteins in the reference collection; more proteins than there are estimated genes in the human genome. The results were compared to the same number of previously sequenced microbial genomes randomly selected from public databases and reported 14,064 novel proteins.

These data suggest that the HMP reference collection has nearly twice the amount of microbial diversity than is represented by microbial genomes already in public databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomeprj). One of the primary goals of the HMP reference collection is to expand researchers' ability to interpret data from metagenomic studies. Metagenomics is the study of a collection of genetic material (genomes) from a mixed community of organisms. Comparing metagenomic sequence data with genomes in the reference collection can help determine the novel or already existing sequences (Hsiao and Fraser-Liggett, 2009). A total of 16.8 million microbial sequences found in public databases have been compared to the genome sequences in the HMP reference collection and it was found that 62 genomes in the reference collection showed similarity with 11.3 million microbial sequences in public databases and 6.9 million of these (41%) correspond with genome sequences in the reference collection (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomeprj).

On the horizon is a new era of molecular medicine characterized less by treating symptoms and more by looking at the most fundamental causes of diseases. Rapid and more specific diagnostic tests will make possible earlier treatment of countless maladies. Medical researchers will also be able to devise novel therapeutic regimens on the basis of new classes of drugs, immunotherapy techniques, avoidance of environmental conditions that may trigger disease, and possible augmentation or even replacement of defective genes through gene therapy.

Despite our reliance on the inhabitants of the microbial world, we know little of their number or their nature. Less than 0.01% of the estimated all microbes have been cultivated and characterized. Microbial genome sequencing will help to lay the foundation for knowledge that will ultimately benefit human health and the environment. The economy will benefit from further industrial applications of microbial capabilities.

Information gleaned from the characterization of complete microbial genomes will lead to insights into the development of such new energy-related biotechnologies as photosynthetic systems and microbial systems that function in extreme environments and organisms that can metabolize readily available renewable resources and waste material with equal facility. Expected benefits also include development of diverse new products, processes, and test methods that will open the door to a cleaner environment. Biomanufacturing will use nontoxic chemicals and enzymes to reduce the cost and improve the efficiency of industrial processes. Microbial enzymes have been used to bleach paper pulp, stone wash denim, remove lipstick from glassware, break down starch in brewing, and coagulate milk protein for cheese production. In the health arena, microbial sequences may help researchers to find new human genes and shed light on the disease-producing properties of pathogens.

Microbial genomics will also help pharmaceutical researchers to gain a better understanding of how pathogenic microbes cause disease. Sequencing these microbes will help to reveal vulnerabilities and identify new drug targets. Gaining a deeper understanding of the microbial world will also provide insights into the strategies and limits of life on this planet, and the human genome sequence will further strengthen our understanding of microbial pathogens and commensals, and vice versa.

Data generated in HMP have helped scientists to identify the minimum number of genes necessary for life and confirm the existence of a third major kingdom of life. Additionally, the new genetic techniques now allow us to establish, more precisely, the diversity of microorganisms and identify those critical to maintaining or restoring the function and integrity of large and small ecosystems; this knowledge can also be useful in monitoring and predicting environmental changes. Finally, studie...