![]()

Chapter 1

The Quick and the Dead: Lessons Learned

The Global Credit Crisis: 2008–2010

The global economy and capital markets have gone through a number of cycles in the 80 years since the Great Depression but none of the downturns has been as dramatic and severe as the credit crisis of 2008–2010. In the span of just eight weeks beginning in September 2008, a “tsunami” swept through the financial markets. The first ripple began on September 7, 2008, when the U.S. government stepped in to prevent the collapse of two cornerstones of the U.S. economy and took control of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in an extraordinary Federal intervention in private enterprise.

A week later, the ripples became waves and on September 14, Lehman Brothers, a 150-year-old institution that had survived the Great Depression, capsized and became the largest company to enter bankruptcy in U.S. history. On the same day, Merrill Lynch agreed to merge with Bank of America in order to avert its own demise. Two days later, AIG, the world's largest insurer, received an US$85-billion bailout package from the U.S. Federal Reserve in order to stave off collapse.

On September 21, with the crisis deepening and just five days after the AIG bailout, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, the two leading providers of financing to the hedge fund industry, sought shelter in safe harbors and received Federal approval to become bank holding companies. This enabled both firms to gain much-needed access to the Federal Reserve's emergency-lending facilities to ensure their liquidity. The move effectively ended the era of investment banking that arose out of the Glass–Steagal Act of 1933, which separated investment banks and commercial banks following the Stock Market Crash of 1929.

Pressures in the financial markets continued to mount and on September 26, Washington Mutual became the largest bank failure in U.S. history when it was seized by Federal regulators. With confidence in the financial markets under intense pressure, the White House and Congress drafted a historic US$700-billion bank rescue plan for the financial sector on September 29. This rescue plan would eventually become known as the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP).

Hedge funds continued to sail in this tempest and navigate a trifecta of forces that threatened their extinction. Some of these privateers understood the limitations of their fragile craft and sought shelter, while others risked their fortunes and sought to profit from opportunities created by the distress. During this turbulent period, concern regarding the health of the hedge fund industry was widespread, as catastrophic investment performance put the entire industry under unprecedented pressure. A record 1,471 individual hedge funds either failed or closed their doors during the credit crisis of 2008. A further 668 closed or failed in the first half of 2009. The difference between those that survived and those that failed is that the latter had great conviction about the future return of their investments while the former knew they could not predict the future, had prepared for uncertainty by investing in their firm's risk management, and followed their risk management discipline to get to a safe harbor until the financial tsunami passed.

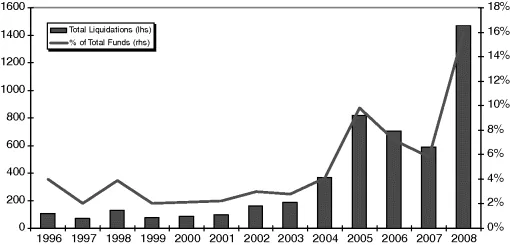

Figure 1.1 shows that the rate of hedge fund failures more than doubled, from less than 7 percent in 2007 to more than 16 percent in 2008.

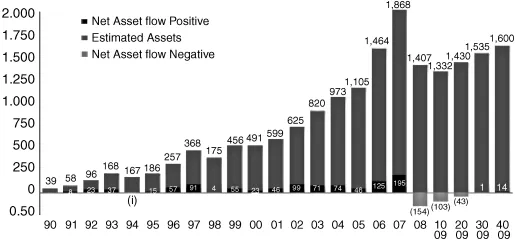

Figure 1.2 shows the massive contraction in assets under management of the hedge fund industry in 2008, as fund performance fell, funds failed, and investors exited hedge fund investments.

Increased Systematic Risk

The first of the three forces threatening the performance and survival of hedge funds was systematic risk. The systematic disruption in the capital markets directly increased the volatility and risk in the markets in which most hedge funds traded. Fundamental systematic risk manifested itself in the form of market volatility and illiquidity, leading to mark-to-market losses for many hedge funds and increased demands for margin from their creditors.

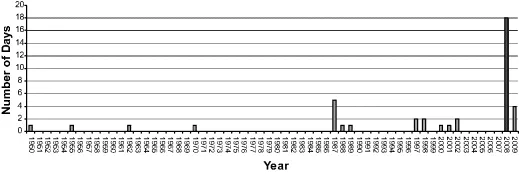

As evident in Figure 1.3, the market volatility during 2008 was unprecedented, with both the frequency and size of large market price movements increasing well beyond historical norms.

The bear market that began after the market peaked in October 2007 was one of the worst bear markets since the 1920s, and second only to the Stock Market Crash of 1929. From the peak of the bull market on October 9, 2007 the broader equity market, as measured by the U.S. S&P 500 index fell more than 58 percent. Over 25 percent of that decline occurred in the 13 days prior to October 16, 2008. Indeed, while all of 2008 was a lethal year for hedge funds, September and October were particularly deadly. As shown in Table 1.1, five of the largest one-day declines ever in the S&P 500 occurred in 2008, and three of those days were in September and October.

Table 1.1 Largest one-day market declines in S&P 500.

Source: Bloomberg

| October 19, 1987 | 20.47 |

| October 15, 2008 | 9.03 |

| December 1, 2008 | 8.93 |

| September 29, 2008 | 8.79 |

| October 26, 1987 | 8.28 |

| October 9, 2008 | 7.62 |

| November 13, 2008 | 6.92 |

| October 27, 1997 | 6.87 |

| August 31, 1998 | 6.80 |

| January 8, 1988 | 6.77 |

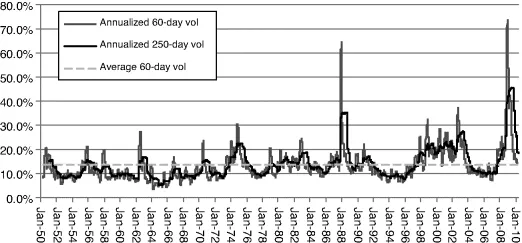

Amid one of the worst bear markets in history, volatility rose to unprecedented levels, surpassing the volatility experienced even on “Black Monday”—October 19, 1987. Figure 1.4 shows the rolling 60-day volatility of the Standard & Poor's 500 Index and allows comparison of volatility levels in prior crises. The levels of volatility realized during the Credit Crisis of 2008–09 surpassed those of the “Black Monday” crisis and all prior crises by more than 15 percent.

By October 15, 2008, volatility had risen to 51.18 percent, equaling Black Monday,1 and continued to grow higher thereafter.

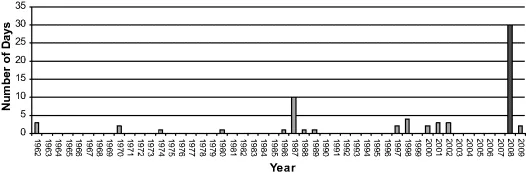

The depth and breadth of the increase in volatility was unprecedented. Between January 1, 2008 and January 1, 2009, the S&P 500 Index closed up or down 5 percent or more on six separate trading days. Never before had any year had as many 5 percent moves.2 In addition, all six of the moves occurred in the trading days in the first half of October 2008. The gauntlet that hedge funds had to run during these two weeks in 2008 was deadly.

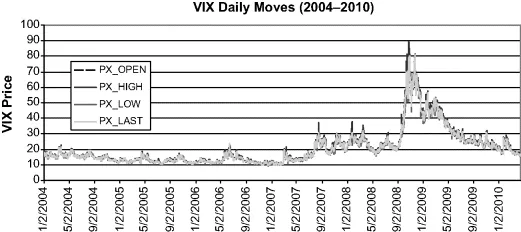

Similarly, as shown in Figure 1.5, the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX), a benchmark market measure of volatility, also reached unprecedented levels.

The CBOE volatility index typically trades in the 10–30 range. However, in October 2008, the index was trading at over 80.

As much as inter-day volatility had increased, intra-day volatility had also increased to levels not previously seen. For the trading days comprising the first half of October 2008, the S&P 500 experienced intra-day price swings of greater than 5 percent on eight occasions. From October 1 through October 16, intra-day volatility of the S&P 500 index (as measured by the difference between the intra-day high and low) went from 2.25 percent to 10.31 percent. This succession of extremely volatile trading days had simply never happened before in the previous 46 years (see Figure 1.6). Similarly, on October 24, 2008, the CBOE Volatility Index reached an all-time intra-day high of 89.53.

Amidst this wind shear in security valuations, the value of hedge-fund portfolios declined and prime brokers increased their margin requirements to protect themselves from losses as hedge fund defaults became increasingly likely. By increasing margin levels, prime brokers increased the collateral they held and reduced the amount of credit extended to hedge funds. The increased margin requirements caused mark-to-market losses to be realized and further drove down security values as hedge funds liquidated positions to generate cash needed to post to their prime brokers and avoid default.

Contraction of the Interbank Funding Markets

The second of the three forces threatening the performance and survival of hedge funds was the freezing of the interbank funding markets. Uncertainty regarding the solvency of major financial institutions caused a severe contraction and the eventual collapse of the interbank funding markets. This eroded the solvency of almost all hedge fund counterparties and led to the sudden failure of several major financial institutions (including Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers). It dramatically weakened broker-dealers such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, which had to convert to bank holding companies in order to use the Federal Reserve's emergency-lending facilities. Hedge funds sought to rapidly withdraw their assets held at these brokers as default concerns mounted, leading to the equivalent of a run on the brokers by the hedge funds. Morgan Stanley reportedly had 95 percent of its excess hedge fund equity requested to be withdrawn within one week.

Investor Redemptions

The third of the three forces threatening the performance and survival of hedge funds was the vicious cycle of de-leveraging that panicked hedge fund investors, causing them to make unrelenting demands to redeem their hedge fund shares. This in turn undermined less-liquid hedge fund investment strategies and forced hedge funds to further realize market losses by selling assets to meet investor demands or forcing them to refuse redemption requests in an effort to ride out the storm without selling assets at distressed prices. Many hedge funds were unprepared for the redemption maelstrom that engulfed them. Several have failed dramatically, while many more quietly gated their fund, slowly liquidated and ultimately shuttered their doors after suffering significant losses.

The Quick and the Dead

Prime brokers provided much of the leverage exploited by hedge funds to generate high returns before the crisis. Essentially, prime brokers, through their margin requirements, determine how much cash a hedge fund needs to post to invest in a security. The prime brokers provide the difference between the price of the security and the margin requirement as financing (essentially a loan) to the hedge fund to finance the purchase of the security. The prime broker holds the security as collateral against the loan. As the security's value rapidly falls, the fund needs to post more cash with the prime broker in order to remain invested in the position.

In the crisis, not only were security values falling (resulting in hedge funds having to post additional cash to remain invested), but several prime brokers were also increasing their percentage of a security's value a hedge fund had to post to own the security. Sometimes this was a specific response to a decline in a particular hedge fund's creditworthiness and sometimes this margin change was applied across all funds holding a certain type of risky asset. Regardless of cause, having to post greater margin further reduced hedge funds' liquidity and available cash to meet redemptions.

Prime brokers, hedge fund managers and their investors faced a prisoner's dilemma3 where, if the demands for cash were balanced, they could all increase the probability they would collectively emerge from the crisis while the first one to individually grab the cash would be certain to minimize their losses. In the crisis...