- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Such Stuff as Dreams: The Psychology of Fiction explores how fiction works in the brains and imagination of both readers and writers.

- Demonstrates how reading fiction can contribute to a greater understanding of, and the ability to change, ourselves

- Informed by the latest psychological research which focuses on, for example, how identification with fictional characters occurs, and how literature can improve social abilities

- Explores traditional aspects of fiction, including character, plot, setting, and theme, as well as a number of classic techniques, such as metaphor, metonymy, defamiliarization, and cues

- Includes extensive end-notes, which ground the work in psychological studies

- Features excerpts from fiction which are discussed throughout the text, including works by William Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Kate Chopin, Anton Chekhov, James Baldwin, and others

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Such Stuff as Dreams by Keith Oatley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Fiction as Dream

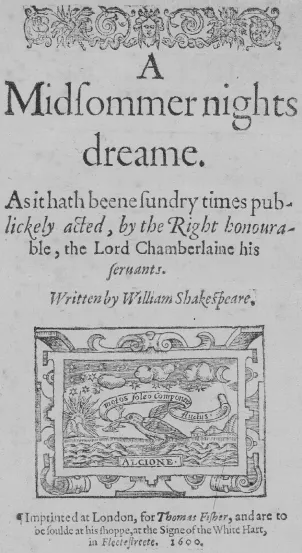

Figure 1.1 Frontispiece of the 1600 edition of A midsummer night’s dream.

Source: The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Fiction as Dream: Models, World-Building, Simulation

Shakespeare and Dream

“Dream” was an important word for William Shakespeare. In his earliest plays he used it with its most common meaning, of a sequence of actions, visual scenes, and emotions that we imagine during sleep and that we sometimes remember when we awake, as well as with its second most common meaning of a waking fantasy (day-dream) of a wishful kind. Two or three years into his playwriting career, he started to use it in a subtly new way, to mean an alternative view of the world, with some aspects like those of the ordinary world, but with others unlike.1 In the dream view, things look different from usual.

In or about December 1594, something changed for Shakespeare.2 What changed was his conception of fiction. He started to believe, I think, that fiction should contain both visible human action and a view of what goes on beneath the surface. His plays moved beyond dramatizations of history as in the three Henry VI plays, beyond entertainments such as The taming of the shrew.3 They came to include aspects of dreams. Just as two eyes, one beside the other, help us to see in three dimensions so, with our ordinary view of the world and an extra view (a dream view), Shakespeare allows us to see our world with another dimension. The plays that he first wrote when he had achieved his idea were A midsummer night’s dream and Romeo and Juliet.

In A midsummer night’s dream it is as if Shakespeare says: imagine a world a bit different from our own, a model world, in which, while we are asleep, some mischievous being might drip into our eyes the juice of “a little western flower” so that, when we awake, we fall in love with the person we first see. This is what happens to Titania, Queen of the Fairies. Puck drips the juice into her eyes. When she wakes, she sees Bottom the weaver, who – in the dream world – has been turned into an ass, and has been singing.

Titania: I pray thee, gentle mortal, sing again:

Mine ear is much enamour’d of thy note;

So is mine eye enthralled to thy shape;

And thy fair virtue’s force perforce doth move me

On the first view to say, to swear, I love thee (1, 3, 959)

Could it be that, rather than considering what kind of person we could commit ourselves to, we first love and then discover in ourselves the words and thoughts and actions that derive from our love?4

A midsummer night’s dream helped Shakespeare, I think, to articulate his idea of theater as model-of-the-world. Although perhaps not as obviously, Romeo and Juliet, which was written at about the same time, comes from the same idea. It starts with a Prologue, which begins like this.

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents’ strife (Prologue, 1).

A model is an artificial thing.5 So Shakespeare doesn’t start Romeo and Juliet with anything you might see in ordinary life. He starts it with someone who is clearly an actor coming on to the stage and addressing the audience in a sonnet. The sonnet form has 14 lines, each having ten syllables with the emphasis on the second syllable of each pair. So this sonnet reads: “Two house-holds both a-like …” This makes for a certain attention-attracting difference, because if you pronounce the verse in this iambic way, and make sure also to emphasize slightly the rhymes at the end of each line, it sounds different from colloquial English.6 The iambic meter seems almost to echo the human heart-beat: te-tum, te-tum, te-tum.

The sonnet at the beginning of Romeo and Juliet tells us the play’s theme. As with A midsummer night’s dream, the play is about the effects of an emotion, once again love. In the what-if world of this play, the threat by the civil authority of punishing public fighting by death is futile. The only thing that will temper hatred is love: in this case the love between the children of the two households, and the love of the parents for their children. This, says the actor who recites the prologue-sonnet, “Is now the two-hour’s traffic of our stage.” Once a different view than usual has been suggested by means of the model world of what-if, each of us in the audience can wonder: “What do we think?”

Shakespeare’s idea of dream had at its center the idea of model, or imagination, that could be compared with the visible aspects of the world. It was extended to include two features that he continued to develop throughout his writing.

One of these features was the relation of surface actions to that which is within. Shakespeare uses a range of words that include: “shadow,” “action,” “show,” “form,” and “play,” to indicate outwardly visible behavior. (Shadow meant what it does today, as well as reflection as in a mirror.)7 To indicate what is deeper and externally invisible in a person, Shakespeare uses another range of words that include: “substance,” “heart,” “mettle,” and “that within.” It’s not that outer behavior is deceptive as compared with that within which is real. That would be banal. Shakespeare typically depicts relations between shadow and substance. This idea of shadow and substance – of actions that are easily visible accompanied by glimpses of what goes on beneath the surface – enables us to compare actions and their meanings.

The second further feature in Shakespeare’s idea of dream is recognition. One form it takes is of a character thinking someone to be whom he or she seems to be on the surface, and then finding this person to be someone else. It’s an extension of the idea of shadow and substance, but with emphasis coming to fall on implications of the recognition. It is the story-outcome of the idea that some aspects of others (and ourselves) are hidden.

Rather than offering quotations that can be tantalizingly insufficient, let me offer a whole piece by Shakespeare that is quite brief. With it we shall be able to see, I hope, how the idea of dream (with its idea of model-in-the imagination, and its features of substance-and-shadow and of recognition) can work together. This piece is Shakespeare’s Sonnet 27, which is as follows.

Sonnet 27: A story in sonnet form

Weary with toil I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired;

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind when body’s work’s expired;

For then my thoughts, from far where I abide,

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide

Looking on darkness which the blind do see:

Save that my soul’s imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which like a jewel hung in ghastly night

Makes black night beauteous and her old face new.

Lo! thus by day my limbs, by night my mind,

For thee, and for myself, no quietness find.

The poet is away. Tired with his work and his travel, he goes to bed. In line 3, there is a metaphor, “journey in my head.” Just as on a journey one visits a series of places so, in one’s mind, one visits a series of thoughts. At the same time, the whole sonnet is a model, a metaphor in the large, and a wide-awake dream, in which the poet thinks of his loved one with urgent feelings.

Although it has only 14 lines, a sonnet is often a story. Or one can think of it as a compression of a story into its turning point. The sonnet form includes an expectation that there will be at least one such turning point. There is also the expectation that the sonnet will reach a conclusion.8

In the sonnet form, the first turning point is expected between lines 8 and 9. This kind of change derives from the earliest kind of sonnet, which is called Petrarchan, after the Italian poet Petrarch. In this form, the first eight lines comprise what is known as the octave. It’s followed at line 9 by the last six lines or sestet – in a way that is like a change of key in music – in which the skilled poet takes us through an important juncture in the story, or enables us to see first part of the poem in a different way. In the slightly different, Elizabethan, form of the sonnet, the change occurs at line 13. In his Sonnet 27, Shakespeare arranges two changes: at line 9 and at line 13.

The octave of Sonnet 27 is a description, as if in a letter: “Weary with toil I haste me to my bed …” Once a reader has worked out that the poet is away from home and that the poem is addressed to the poet’s beloved, the meaning seems clear. The poet goes to bed tired, wanting to sleep and, as he lies in bed, he thinks of his loved one, far away. Perhaps the journey in his head retraces the physical journey away from his loved one. But as the reader starts to think about it, this idea doesn’t quite make sense. If the poet were merely missing his beloved, there would be longing, perhaps memories of being together. There’s nothing of the sort. So the reader has to think harder. The poet has already complained that his daytime work is wearying. Now, in bed, the act of thinking about his beloved is work (another metaphor). These are not fond thoughts of the loved one. The metaphor implies that these thoughts, too, are wearying.

Shakespeare chooses words carefully. He doesn’t write “eager pilgrimage to thee.” He writes “zealous pilgrimage to thee” with “zealous” perhaps having the word “jealous” hiding behind it.9 We might also think that a connotation of “zealous” is “slightly crazy.” Why is the poet lying with “eyelids open wide,” although they are “drooping?” He stares into the darkness, unable to see. “Looking on darkness which the blind do see.” He’s like a blind person, a person blinded by – what?

When line 9 is reached a change, or turning point, occurs to the last six lines, the sestet. It offers a different view:10 “Save that my soul’s imaginary sight.” In other words, the poet says: “What has gone before is right, it’s dark and I can’t see, except that …” suddenly the poet can see his loved one – all too clearly – in his imagination. That’s what’s keeping him awake. In the poet’s imaginary sight comes Shakespeare’s use of “shadow” (meaning externally visible actions), with its implicit contrast with substance (meaning who the loved one really is).

The beloved is beautiful, and therefore “like a jewel.” But what a juxtaposition: “hung in ghastly night.” The poet lies in bed, and imagines what his beautiful beloved might be up to. It’s ghastly! The poet imagines that his beloved is not lying quietly in bed, not asleep. The beloved is doing something else. What?

The poet tries to wrench his mind around, to counter this distressing idea. In the twelfth line he offers the poem’s only positive thought of the loved one, who makes t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Fiction as Dream

- 2 The Space-In-Between

- 3 Creativity

- 4 Character, Action, Incident

- 5 Emotions

- 6 Writing Fiction

- 7 Effects of Fiction

- 8 Talking About Fiction

- Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index