eBook - ePub

Cancer Epigenetics

Biomolecular Therapeutics in Human Cancer

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cancer Epigenetics

Biomolecular Therapeutics in Human Cancer

About this book

Cancer Epigenetics: Biomolecular Therapeutics in Human Cancer is the only resource to focus on biomolecular approaches to cancer therapy. Its presentation of the latest research in cancer biology reflects the interdisciplinary nature of the field and aims to facilitate collaboration between the basic, translational, and clinical sciences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cancer Epigenetics by Antonio Giordano, Marcella Macaluso, Antonio Giordano,Marcella Macaluso in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Oncology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

EPIGENETICS AND CELL CYCLE

Chapter 1

Epigenetic Modulation of Cell Cycle: an Overview

1.1 Introduction

The progression of the cell cycle is a very finely tuned process that responds to the specific needs of any specific tissue or cell, and is strictly controlled by intrinsic and extrinsic surveillance mechanisms (Giacinti and Giordano, 2006; Montanari et al., 2006; Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009). The intrinsic mechanisms appear at every cycle whereas the extrinsic mechanisms only act when defects are detected (Macaluso and Giordano, 2004; Johnson, 2009). The loss of these control mechanisms by genetic and epigenetic alterations leads to genomic instability, accumulation of DNA damage, uncontrolled cell proliferation, and eventually, tumor development. While genetic abnormalities are associated with changes in DNA sequence, epigenetic events alter the heritable state of gene expression and chromatin organization without change in DNA sequence. The most studied epigenetic modifications of DNA in mammals are methylation of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides (DNA methylation), imprinting, posttranslational modification of histones (principally changes in phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination status), and small RNA-mediated control, specifically miRNAs (Garzon et al., 2009; Kampranis and Tsichlis, 2009; Mendez, 2009; Simon and Kingston, 2009). Important biological processes are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, including gene reprogramming during early embryogenesis and gametogenesis, cellular differentiation, and maintenance of a committed lineage. Epigenetic marks are established early during development and differentiation; however, modifications occur all through the life in response to a variety of intrinsic and environmental stimuli, which may lead to disease and cancer (Delcuve et al., 2009; Maccani and Marsit, 2009). Although the importance of genetic alterations in cancer has been long recognized, the appreciation of epigenetic changes is more recent. Numerous studies have provided evidence that aberrant epigenetic mechanisms affect the transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, apoptosis, and genome integrity, and play an important role in cancer formation and progression (Humeniuk et al., 2009; Lopez et al., 2009; Toyota et al., 2009).

1.2 Epigenetic and Genetic Alterations of pRb and p53 Pathways

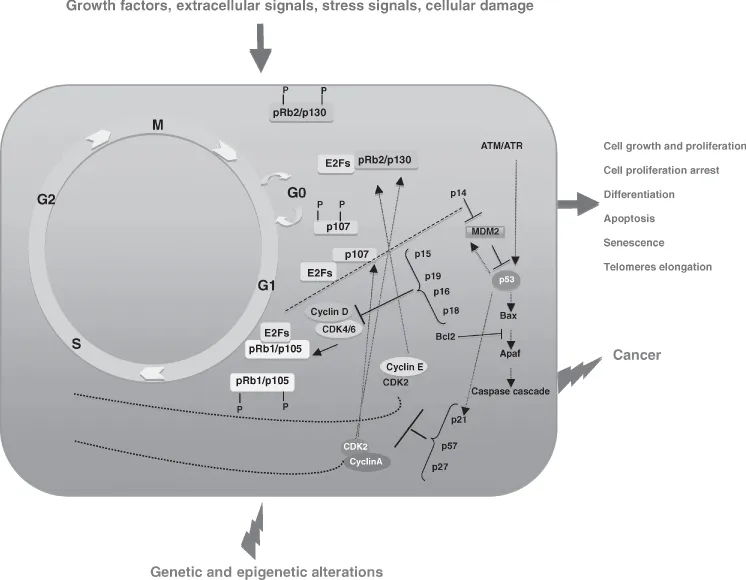

The progression of the cell cycle is tightly monitored by surveillance mechanisms, or cell cycle checkpoints, which ensure that the initiation of a later event is coupled with the completion of an early cell cycle event. The pRb (pRb/p16INK4/Cyclin D1) and p53 (p14ARF/mdm2/p53) pathways are the two main cell cycle control pathways (Fig. 1.1). The importance of these pathways in controlling cellular growth and apoptosis is underscored by many studies, indicating that mutations of the components of these pathways in all human cancers. Almost all human cancers show deregulation of either the pRb or p53 pathway, and often both pathways simultaneously (Macaluso et al., 2006; Yamasaki, 2006; Polager and Ginsberg, 2009).

Figure 1.1 A combinatorial signaling network between pRb (pRb/p16INK4/cyclin D1) and p53 (p14ARF/mdm2/p53) pathways control cell cycle progression through an array of autoregulatory feedback loops where pRb and p53 signals exhibit very intricate interactions with other proteins involved in the determination of cell fate. Loss of cell cycle control by genetic and epigenetic alterations leads to genomic instability, accumulation of DNA damage, uncontrolled cell proliferation, and eventually tumor development. (See insert for color representation of the figure.)

A combinatorial signaling network between pRb and p53 pathways controls cell cycle progression through an array of autoregulatory feedback loops where pRb and p53 signals exhibit very intricate interactions with other proteins involved in the determination of cell fate (Hallstrom and Nevins, 2009; Polager and Ginsberg, 2009).

Alterations in the pRb and/or p53 pathway converge to reach a common goal: uncontrolled cell cycle progression, cell growth, and proliferation. Then, loss of cell cycle control may lead to hyperplasia and eventually to tumor formation and progression (Sun et al., 2007; Lapenna and Giordano, 2009; Polager and Ginsberg, 2009).

1.2.1 pRb (pRb/p16INK4/Cyclin D1) Pathway

Several studies have documented the role of the pRb pathway, and its family members pRb2/p130 and p107, in regulating the progression through the G1 phase of the mammalian cell cycle (Giacinti and Giordano, 2006; Johnson, 2009; Poznic, 2009). In addition to pRb family proteins, key components of this pathway include the G1 cyclins, the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and the CDK inhibitors (Lapenna and Giordano, 2009; Poznic, 2009).

Alterations in the signaling network in which pRb, p107, and pRb2/p130 act have been reported in most human cancers. Genetic changes, such as mutations, insertions, and deletions, and also epigenetic alterations, such as promoter hypermethylation, are the most common molecular alterations affecting the function of pRb family proteins. Moreover, it has been reported that inherited allelic loss of pRb confers increased susceptibility to cancer formation (Mastrangelo et al., 2008; Sabado Alvarez, 2008; Poznic, 2009).

Numerous observations have indicated that pRb family proteins interact with a variety of transcription factors and chromatin-modifying enzymes (Brehm et al., 1998; Harbour et al., 1999; Macaluso et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the binding of pRb family proteins with the E2F family of transcription factors appears to be crucial in governing the progression of the cell cycle and the DNA replication by controlling the expression of cell cycle E2F-dependent genes. These genes include CCNE1 (cyclin E1), CCNA2 (cyclin A2), and CDC25A, which are all essential for the entry into the S phase of the cell cycle, and genes that are involved in the regulation of DNA replication, such as CDC6, DHFR, and TK1 (thymidine kinase) (Attwooll et al., 2004; Polager and Ginsberg, 2009). The INK4a/ARF locus (9p21) encodes two unique and unrelated proteins, p16INK4a and p14ARF, which act as tumor suppressors by modulating the responses to hyperproliferative signals (Quelle et al., 1995). One of the most frequent alterations affecting the pRb pathway regulation in cancer involves p16INK4a. Loss of p16INK4a occurs more frequently than loss of pRb, suggesting that p16INK4a suppresses cancer by regulating pRb as well as p107 and pRb2/p130. Loss of function of p16INK4a by gene deletion, promoter methylation, and mutation within the reading frame has frequently been found in human cancers (Sherr and McCormic, 2002). Different studies have indicated that p16INK4A can modulate the activity of pRb and it also seems to be under pRb regulatory control itself (Semczuk and Jacowicki, 2004). p16INK4a blocks cell cycle progression by binding Cdk4/6 and inhibiting the action of D-type cyclins. Moreover, p16INK4a controls cell proliferation through inhibition of pRb phosphorylation, then promotes the formation of pRb-E2Fs repressing complexes, which blocks the G1–S-phase progression of the cell cycle (Zhang et al., 1999). It has been reported that pRb forms a repressor containing histone deacetylase (HDAC) and the hSWI/SNF nucleosome remodeling complex, which inhibits transcription of genes for cyclins E and A, and arrests cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Zhang et al., 2000). Both cyclin D1 overexpression and p16INK4a protein alteration produce persistent hyperphosphorylation of pRb, resulting in evasion of cell cycle arrest. Phosphorylation of pRb by cyclin D/cdk4 disrupts the association of the HDAC-Rb-hSWI/SNF complex, relieving repression of the cyclin E gene and G1 arrest. However, the persistence of Rb-hSWI/SNF complex appears to be sufficient to maintain the repression of the cyclin A and cdc2 genes, inhibiting exit from S phase (Zhang et al., 2000; Beasley et al., 2003). Interestingly, there is evidence that suppression of pRb2/p130, perhaps due to epigenetic alterations, abolishes the G1–S phase block, leads to cyclin A expression, and extends S-phase activity. In addition, it has also been reported that overexpression of p16INK4a or p21 causes accumulation of pRb2/p130 and senescence (Helmbold et al., 2009; Fiorentino et al., 2011). While p16INK4a mutations are not commonly reported, small homozygous deletions are the major mechanism of p16INK4a inactivation in different primary tumors such as glial tumors and mesotheliomas. The INK4a/ARF locus on 9p21 is deleted or rearranged in a large number of human cancers, and germline mutations in the gene have been shown to confer an inherited susceptibility to malignant melanoma and pancreatic carcinoma (Meyle and Guldberg, 2009; Scaini et al., 2009). Interestingly, it has been reported an increased risk of breast cancer in melanoma prone kindreds, owing to the inactivation of p16INK4a, p14ARF or both genes (Prowse et al., 2003). Aberrant methylation of p16INK4a has been reported in a wide variety of human tumors including tumors of the head and neck, colon, lung, breast, bladder, and esophagus (Blanco et al., 2007; Gold and Kim, 2009; Goto et al., 2009; Phe et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2010). Inactivation of the p16INK4a gene by promoter hypermethylation has been frequently reported in approximately 50% of human, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Zhu et al., 2006). Moreover, p16INK4a loss in preneoplastic lesions occurred exclusively in patients who also showed loss of p16INK4a expression in their related invasive carcinoma, indicating that p16INK4a may constitute a new biomarker for early diagnosis of this disease (Brambilla et al., 1999; Beasley et al., 2003).

Deregulated tumor expression of p16INK4a has been described in association with clinical progression in sporadic colorectal cancer (CRC) patients (McCloud et al., 2004). p16INK4a hypermethylation has been shown to occur in advanced colorectal tumors and has been associated with patient survival (Cui et al., 2004). Significant correlation has also been reported between aberrant p16INK4a methylation and Dukes' stage and lymphatic invasion in colorectal carcinoma (Goto et al., 2009). Although the inactivation of p16INK4a seems to be a crucial event in the development of several human tumors, the relevance of this alteration in mammary carcinogenesis remains unclear. For example, p16INK4a homozygous deletions have been reported in 40–60% of breast cancer cell lines, while both homozygous deletions and point mutations are not frequently observed in primary breast carcinoma, suggesting that these alterations might have been acquired in culture (Silva et al., 2003). In addition, p16INK4a hypermethylation has been reported in breast carcinoma, although the relevance of this p16INK4a alteration is discordant among different studies (Lehmann et al., 2002; Tlsty et al., 2004). Interestingly, although methylation of p16INK4a promoter is common in cancer cells, it has been reported that epithelial cells from histologically normal-appearing mammary tissue of a significant fraction of healthy women show p16 promoter methylation as well (Holst et al., 2003; Bean et al., 2007). However, a recent study indicates a strong association between aberrant p16INK4a methylation and breast-cancer-specific mortality (Xu et al., 2010). Cyclin alteration represents one of the major factors leading to cancer formation and progression. Evidence indicates that a combination of cyclin/cdks, rather than a single kinase, executes pRb phosphorylation and at specific pRb-phosphorylation sites (Mittnacht, 2005). Moreover, it has been reported that the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) leads to pRb inactivation b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication Page

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I: Epigenetics and Cell Cycle

- Part II: Epigenetics and Cell Development, Senescence and Differentiation

- Part III: Epigenetics and Gene Transcription

- Part IV: Epigenetics and Cancer

- Part V: Epigenetics and Anticancer Drug Development and Therapy

- Index