![]()

SECTION 1

Introductory Material

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Potential Advantages of Using Biomimetic Alternatives

Jamie Davies

Introduction

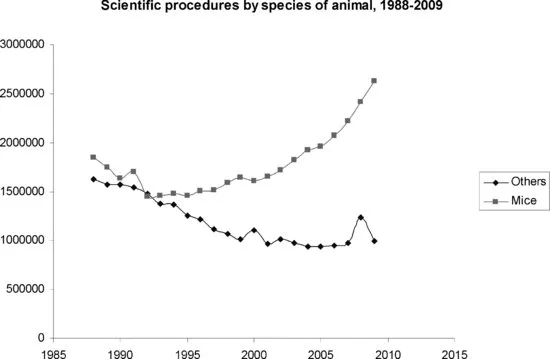

Animal experimentation has long been one of the cornerstones of biological and biomedical research. In fields from surgery to physiology and from pathology to pharmacology, in vivo models have been dominant for well over a century. It can be argued that many of the successes of modern medicine have been based on animal work. Examples include the use of dogs in the discovery of insulin and its use as a treatment for diabetes mellitus1,2, the use of cats for the invention of the heart–lung machine3, the use of mice in the development of penicillin as a clinical antibiotic4, of rats in the identification of the first drugs effective against psychiatric disorders5 and of mice in the development of clinically-useful antiviral compounds6. In recent decades, the rise of transgenic technology has meant that even fields such as molecular biology, that traditionally used cells rather than animals, now involve a significant number of in vivo studies. Current enthusiasm for transgenic mice has meant that a previously gently declining rate of use of vertebrate animals in science has reversed to become a steady rise (Figure 1.1).

With the apparent historical success of in vivo investigations, it may seem surprising that so many scientists are now putting so much effort into developing alternatives. There are, however, good reasons for this development, some based on avoiding or reducing the problems that have always been associated with animal work, and some aiming to maximize the opportunities that new technologies make available. The purpose of this short introductory chapter is to give an overview of some of the reasons to consider developing culture-based alternatives or, where a move to an entirely culture-based programme of work would be inadvisable, to consider ways to combine culture and whole-animal approaches.

The main reasons for considering alternatives can be divided, albeit with some room for debate about precise boundaries, into wholly scientific reasons connected with the quality and usefulness of the experimental data that may be obtained, and non-scientific reasons connected with costs, time, ethics, law and public image. Naturally, in most situations scientific progress is itself highly dependent on these non-scientific considerations, for the rate of scientific progress is limited by the availability of time and money, and the latter is much influenced by good will. Despite this connection, the reasons are considered separately in this chapter because clear discussion of the advantages of culture-based systems is all too often compromised by a conflation of very different ideas. In particular, sometimes strident presentation of ethical reasons to move to culture systems has tended to obscure strong but quieter arguments for scientific advantages and opportunities that such a move sometimes makes available. This bookis written by scientists, for scientists, and therefore leads with scientific reasons for exploring cultured biomimetic assay systems.

It should be noted that, in this book, the word ‘animal’ is generally used in the context of a species given some form of legal protection, such as by the UK's Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act. These are generally vertebrate species, although some invertebrate animals such as Octopus are also protected. Most jurisdictions permit experimentation on ‘lower’ animals, such as fruitflies and nematode worms, without restriction and these organisms are also generally very cheap to keep and require little space. This book does not therefore address the replacement of experiments performed in ‘lower’ animals with culture-based alternatives specifically, because there are fewer benefits from doing so and fewer external pressures to make such a transition. Nevertheless, the general principles outlined by later chapters should still apply and should be adaptable to invertebrate systems if anyone wishes to do this.

Scientific reasons to consider alternatives

Accessibilty

With a few exceptions, such as skin, hair, eyes and oral mucosa, most mammalian tissues reside deep inside an opaque animal. That makes them difficult to observe in a living state, and means that studies of the time-course of a natural phenomenon such as development, or of the progress of a disease or of healing, are frequently done by killing groups of experimental animals after a series of time intervals and making some kind of average measurement that can be used to compare the time-course of the process at different times. As well as involving the expense of large animal numbers, this approach throws away details that might be gleaned by following the time-course of events within the same animal. Also, information about real variation, where it is present, is lost as ‘noise’ in the data rather than appearing as clear evidence that disease in different individuals might follow a consistently different course.

Modern imaging technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound ameliorate this problem to some extent, allowing non-invasive imaging of objects such as cysts and tumours7–9. Unfortunately, their use requires immobilization of the animal, which may induce stress and affect results. The resolution of these techniques is also limited; they do not yet yield information at the cellular level, although labelling test cells with contrast agents can approach this10. Transgenic luminescent reporter mice, and luminescent reporter pathogens, allow in vivo imaging of anatomy, events or infections11,12 but the preparatory work can be complicated (for example, engineering the mice) and again the resolution is limited, especially for deep tissues.

In contrast to these problems, cultured organs or tissues can be put under the microscope at any time and can even be filmed continuously with cellular or sub-cellular resolution. Even where a transgenic reporter mouse is used as a source of the tissue, the improved access allowed by culture models can allow much better imaging than could be performed in vivo. An example of the power of this approach is provided Frank Costantini's group, who used live imaging of GFP-expressing cells in organ culture to provide a very high-resolution study of cellular dynamics during branching morphogenesis13,14.

Reduction of confounding variables

Not all biomedical research is intended to measure the effects of some experimental intervention on a whole organism; rather, many experiments aim to determine the direct effect on one specific cell or tissue. Under these circumstances, the presence of other body systems, which might also have their own reaction to the intervention, can make what should be a ‘clean’ experiment very messy. Classical gene knockout experiments, for example, will remove a gene from all of the tissues that express it. Given that many very important signalling pathways are used for different purposes by different cells, removal of the gene can create a complex whole-body phenotype that only partly reflects the gene's role in the tissue of interest: worse, some of the effects on that tissue might be mediated indirectly from unknown signals from the rest of the body. This can be circumvented to some extent by the use of conditional knockouts15, although even there it can be difficult to identify driver promoters that are expressed in only one location from only the time of interest. Exactly the same argument applies to small molecule agonists and antagonists that are used to investigate physiology.

Another ‘whole-body’ complication is the metabolism of drugs, particularly by liver and to some extent kidney, and their excretion. The opportunity to escape metabolic effects mediated by remote tissues is double-edged. Where the molecule being applied is itself pharmacologically active, escaping the whole-body situation allows experimenters to avoid rapidly changing concentrations and the appearance of new metabolites. Where drug is itself inert and has to be metabolized into an active moiety, on the other hand, the lack of a functioning liver would be a problem (although this can be circumvented somewhat by transfecting cells with constitutively-active genes encoding proteins such as cytochrome p450, which enables them to perform some ‘liver-type’ drug metabolism16). For larger molecules, from high molecular weight drugs to growth factors, antibodies, nucleic acids and other ‘biological’ pharmaceuticals, the reaction of the immune system can be a particular problem, especially as the magnitude of its contribution may become larger on each injection. Even where the eventual aim of a research programme is to develop a drug that can be used safely in the whole body, initial investigations into physiological mechanisms are often achieved most easily by large biological molecules such a natural growth factors, antibody or nucleic acid, so that the value of a drug target can be confirmed before much effort is expended in developing smaller, non-immunogenic versions.

In all of the these cases, an ability to study only the tissue of interest in culture, free of any other tissues and free of an immune system, can be a great advantage. It allows experimenters to use reagents that would provoke additional effects elsewhere in the body, or even be downright toxic.

Following disease processes to the end

In most countries that have strong research communities, investigations into pathological processes in whole animals are limited by ethical and legal requirements not to keep an animal in serious suffering. Pathologists studying disease processes are therefore prevented from observing the events that take place beyond this point as the animal must be destroyed humanely. In a culture-based alternative, there is no limit to how much destruction an infective agent might be allowed to wreak, and pathological events can be studied to their end. There will naturally be a difference between what is seen in an isolated tissue and what may be seen in a whole body, with its complex feedback systems and a active immune and inflammatory responses, but for at least some questions valuable data can be gained from examination of infected tissue in isolation.

Fidelity and safety

Where animals are being used as a proxy for people, for example in the modelling of a human disease, the testing of a drug or the safety testing of a chemical, there is another problem: while evolutionary homology means that the physiologies of different mammals are generally very similar, it does not imply that they are always exactly the same. Where they are not, there is the potential for two opposite types of error, the ‘false-positive’ and ‘false negative’ (‘false’ meaning, in this case, not giving a result that will be true in human).

For efficacy testing, false negatives do not carry risk of iatrogenic harm but they do result in a missed opportunity. They happen when a drug or other intervention that is potentially very useful in humans is wrongly seen to be ineffective because it does not work in an experimental animal. For safety testing, a false danger result will occur when a drug that is actually safe for human use generates a serious adverse effect in another species. Because of the historical reliance on animal testing, it is difficult to gather statistics on how common this effect is directly, as many compounds with adverse effects on animal models will never have been tested in humans. Some attempts to perform statistical studies using drugs that were finally accepted for human use have been made: an example, by Fletcher17, focused on a series of 45 drugs assessed during the 1970s by the UK Committee on the Safety of Medicines. The study examined reports of the different specific types of toxic/adverse reaction (vomiting, ataxia, etc.; a total of 26 categories) in all species tested, including human, to determine the extent of correlation between data from humans and from non-human animals: of the 45 drugs, 13 showed no correlation at all and 17 showed only one correlating symptom. The author summarized the d...