- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

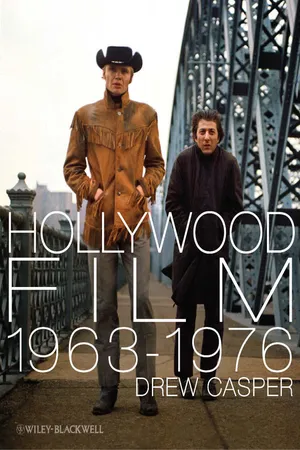

Hollywood 1963-1976 chronicles the upheaval and innovation that took place in the American film industry during an era of pervasive cultural tumult. Exploring the many ideologies embraced by an increasingly diverse Hollywood, Casper offers a comprehensive canon, covering the period's classics as well as its brilliant but overlooked masterpieces.

- A broad overview and analysis of one of American film's most important and innovative periods

- Offers a new, more expansive take on the accepted canon of the era

- Includes films expressing ideologies contrary to the misremembered leftist slant

- Explores and fully contextualizes the dominant genres of the 60s and 70s

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hollywood Film 1963-1976 by Drew Casper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Cultural Overview

Cultural Overview

The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1963–76

Introduction

Not since the Civil War (1861–5) had America been as splintered, unsure, and perturbed as it was between 1963 and 1976. Liberals pushed and got strident. Conservatives held their ground and stiffened. The country embraced Johnson and then Nixon. The government expanded an individual’s rights, but by infiltrating practically every sphere of human endeavor, it undermined an individual’s power. Welfare collided with the work ethic; comfy socialism with rugged individualism. Uncivil in-your-face confrontations and defiant let-it-all-hang-out stances appeared alongside civil coverups and tucked-away conspiracies. Blacks defied whites while militant blacks upbraided non-violent ones. Females battled with males while feminists roiled at many contented housewives. Gays paraded in front of straights. The “responsibility” singsong filtered through the incessant screech about “rights.” Hawks countered doves; some even became doves. The Cold War got colder and then began to thaw. Change vied with continuity. The “Great Society” was becoming anything but. Optimism curdled into cynicism.

The economy, too, behaved schizophrenically, expanding proudly and then shrinking shamefully. The New Left crystallized with the “Students for a Democratic Society” and a counterculture sprang up, affronting the mainstream. Though a minority, the New Left and Counterculture were vociferous. On the right, neoconservatism gathered steam, especially down South and in California. Conservatives, centrists, and many moderate liberals, though a majority, were silent. Ethics and morals were spot-on for some and muddied for others, while Big Business came up with its own set of standards. Nature soothed; science/technology threatened. Media coincidentally broadened and narrowed spectators’ perspectives. Youth went along with or thumbed their noses at their middle-aged parents. “Me” became the center of the universe for many, while for others, “me” was still a part of the universe. Release countered restraint. Crime escalated, while the Supreme Court affirmed the rights of the accused, many of whom were now considered victims. Liberal-tinged religion looked to the here-and-now; the conservative brand anticipated the last days. Nostalgia anodized the current state of stress.

1

Major Historical Events

Major Historical Events

Civil Rights Legislation and Protests

Liberal Democrat President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963 at age 46 by an unbalanced Lee Harvey Oswald, an ex-marine with Communist sympathies, now a Dallas Book Depository order-filler. He, in turn, was shot by saloon-keeper Jack Ruby.1 Dashed was Kennedy’s dream of “A New Frontier.”2 Such horrifying absurdity hatched countless conspiracy theories, all of which the Warren Commission, after a ten-month investigation, declared unfounded in 1964. Nevertheless, the theories still perdured.3

Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson took charge and was elected in 1964 with running mate Hubert Humphrey, defeating arch-conservative Barry Goldwater. Johnson saw himself fulfilling Kennedy’s promise in the institution of a program of liberal-economic/social reform and in the clash with communism in Vietnam, ushering in “A Great Society.”

Johnson’s 1964 civil rights platform,4 helped by a Democrat-majority Congress of 1960 and 1964, was the most sweeping civil rights legislation yet. In public facilities, the workplace, and labor unions, discrimination became a crime. A 1965 Executive Order required any company with federal contracts to ensure that applicants were employed without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin (“sex” was added two years later), setting in motion the policy of “affirmative action,” “quotas,” and “goals and timetables.”

This body of laws was actually energized by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Birmingham, Alabama demonstrations in April, 1963 and his 250,000-strong-march on the nation’s Capitol later that summer, in which the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) also famously declared: “I have a dream … .” The throng sang in kind: “We Shall Overcome,” which became the anthem of Civil Rights. The on-alert National American Association of Colored People (NAACP) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and its Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) backed King. Moreover, the 1964 looting and burning of Birmingham by blacks sped legislation along. And for about the next five years, the marches continued. So did the urban riots, adopting another chant: “Burn, Baby, Burn.”

Fueling the riots were racial discrimination and the poverty level of one-third of the nation’s blacks (10 percent of the population) and the rise of militant blacks countering King and the NAACP’s Christian/Gandhian politics. Black Muslim5 Malcolm X, assassinated in 1965 by rivals, advocated black supremacy and a separate nation for blacks. Stokely Carmichael helped coin the term “black power.” H. “Rap Brown” championed “guerrilla war on the ‘honkie white man.’” Huey P. Newton and Bobby Searle’s 1966 Black Panther Party subscribed to terrorist tactics.

In 1965, King’s march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama to petition Governor George Wallace for protection of blacks registering to vote – which began with a bloody mêlée between protesters and police – precipitated the passing of the Voting Rights Act, assuring federal protection with regard to discriminatory registration criteria as well as the right to vote in city/state/federal elections.

The first black cabinet member, Robert Weaver, took office as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development; the first black Senator, Republican Edward Brooke, in 1966. Effective, two years later: an Open Housing Act outlawing discrimination in rental/sale of houses.

And then, small-time crook-ex-con James Earl Ray assassinated King in Memphis on April 4, 1968. Riots were recorded in 130 cities, piling up over a billion dollars in wreckage.

All along, the liberally-led Republican Earl Warren’s Supreme Court, left-skewed with the appointments of Justices Goldberg and the first black Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall in 1967 (liberal William Brennan had been on the bench since 1956), took up infringement cases or rights issues, such as its 1970 ruling on the legality of school “busing” to achieve integration. The number of respective legislature representatives was to be equally apportioned to the size of the population districts. New guarantees of citizens traveling abroad, privacy in areas of search/seizure, the sale of contraceptives and abortion, interracial marriage, academic freedom, and a “free speech” press went into effect, as did anti-anti-porn laws and expanded immigration rulings. Laws were passed protecting “suspected” criminals, not victims of crime, police, and/or prosecutors: the banning of illegally seized evidence from state trials (Mapp v. Ohio, 1961); a suspect’s right to counsel on appeal (Douglas v. Calif., 1963) and right to counsel in state trials (Gideon v. Wainright, 1963); the exclusion of a suspect’s confessions if a suspect was refused a lawyer after requesting one (Escobedo v. Illinois, 1964); informing suspects of their the rights (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966); all of which raised the hackles of Dirty Harry (WB, 1971) and just about every protagonist in the vigilante thriller cycle (Death Wish, P, 1974). Prayers and Bible readings were verboten in public schools; evolution could be taught – both decisions in accordance with the First Amendment’s separation of church and state.

Allied with the black civil rights push, but less virulent and pervasive, were the stirrings of Native Americans and Hispanics.

Representation of blacks, played by blacks, flooded the screen. Interracial coupling was pictured as far more an accepted situation (The Omega Man, WB, 1971) than a conflictual one, as in postwar films (Island in the Sun, TCF, 1957). Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (C, 1967) was more throwback than breakthrough. Representations of Indians in westerns continued along their postwar enlightened way, while the status of the contemporary Indian was addressed again and again (Flap, WB, 1970). Chief Dan George (Little Big Man, CCF, 1970) became a recognized character actor. Mexicans populated westerns (Blue, P, 1968).

The Civil Rights movement spurred on women’s and gay rights. (Even elderly Americans got into the swing of things by forming the activist “Gray Panthers” organization.) Oppression of women, the slow-growing Women’s Movement believed, was rooted in the institution of marriage, which confined women to the home and to the care of children, along with cultural assumptions that excluded middle-class women from certain work arenas while relegating working-class women to a small range of allowable jobs. Betty Freidan, author of 1963’s The Feminine Mystique, which depicted postwar American women as victims of a culture that convinced them that the fulfillment of their femininity was found in sexual passivity, male domination, and nurturing maternal love, in part created and presided over the National Organization of Women (NOW) in 1966. NOW drafted an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Congress enthusiastically launched the ERA but it eventually floundered.6 Kate Millet’s 1968 Sexual Politics argued that sex can and should be politicized and that patriarchy had hegemonic control in literature. In 1970, a Grove Press sit-in protested the use of the female body as a sex-object to sell liberation to the male. Co-founded by Gloria Steinem, the feminist magazine Ms. hit newsstands in 1972. In 1973’s controversial Roe v. Wade decision, the Supreme Court ruled abortion legal during the first three months of pregnancy. The years 1969–73 were prime for female activists, who consisted mostly of white, middle-class, this-side-of-40 educated women.

This ferment, lo and behold, did not compute on theatrical screens. In fact, 1963–76 was the driest time for female representation and casting in movies since most genres, especially the new ones, handed the male narrative control. Male/female sharing occurred, however, in romantic comedy, romance melo, the outlaw romantic couple on the run, and the comic caper. Only in the female melo did the female hold forth while, in the musical, the female almost gave the male a run for his money, lagging only 12 percent behind the male in number of films constructed around her. An instance of period retrograde, female diminishment that started up postwar got worse.

Along with the impetus for gender equality, other voices rose on the issue of sexual identity and equality. Stonewall Inn, a Greenwich Village bar on Christopher Street, was the site of a five-day riot when gays resisted police harassment in 1969. The following year, gay rights demonstrations in Manhattan decried laws that made homosexual acts illegal and Gay Pride marches enlivened cities. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) stopped defining homosexuality as a psychological disorder in 1973. Between 1971 and 1980, 22 states took their sodomy laws off the books (Illinois was the first in 1962) and some 40 cities made discrimination based on sexual orientation an offense. By 1975, civil service jobs were opened to homosexuals.

Once in a blue moon, homosexuals were principals (Staircase, TCF, 1969; The Boys in the Band, CCF, 1970). As supports, they filled the frames, in likely spots (antique dealer in The Anderson Tapes, C, 1971) as well as unlikely ones (two gentle gunmen proud of their jobs and in love with each other in the James Bond spy thriller Diamonds Are Forever, UA, 1971). Some were flaming transvestites (Cleopatra, TCF, 1963); others were middle-class inconspicuous (The Day of the Jackal, U, 1973) or closeted (Up the Down Staircase, WB, 1967). Bisexuals were also present (Deadfall, TCF, 1968). Gay sexual acts were shown (Fortune and Men’s Eyes, MGM, 1971). Lesbians (Coffy, AIP, 1973), lesbian sex (The Killing of Sister George, ABC, 1969), and female bisexuals (Women in Love, UA, 1970) were represented. Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (TCF, 1970) and The Rocky Horror Picture Show (TCF, 1975) contained just about every homosexual and heterosexual type and positioning.

Figure 1.1 Sunday Bloody Sunday: the film features homosexuality (Peter Finch) and bisexuality (Murray Head), along with heterosexuality (Glenda Jackson) (UA, 1971, p Joseph Janni)

The Vietnam War

In a remote part of the world no one had heard of, a quagmire was festering. The murder of South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem and the collapse of his regime in 1963 caused Kennedy to dispatch about 16,000 troops and economic aid. Diem’s generals, in tacit agreement with Saigon’s US Ambassador, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and Kennedy, had maneuvered the dictatorial, corrupt Diem’s death after he had sent out peace feelers to Hanoi in the Communist north. A good part of Kennedy’s dream, shaped by his deputy national security advisor Walt Rostow, was to win the Cold War and destroy communism. The Green Berets, a counter-insurgency force approved by Kennedy, were already working the land before the coup.

In 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats fired on an US destroyer patrolling the Gulf of Tonkin. Johnson kept the matter from the public and sent in another destroyer while reporting further developments falsely. He further inveigled Congress to pass a resolution to allow the president “to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against US forces and prevent further aggression.” (Congress repealed this proposition in 1971.)7 In 1965, air bombing began after an attack on a US airbase in Pleiku. The skirmish intensified. By the year’s end 200,000 troops had been added; 536,000 by 1968. With arrogant Johnson’s expansion of Kennedy’s policy, the Cold War in Asia became the Vietnam War.

In the conflict with worldwide communism, similar scenarios played out on other stages: troop/aid deployment and CIA and US military counter-insurgency training which, alas, led to repressive military regimes (the Congo, Iraq, Indonesia, Taiwan, the Philippines, South Korea, the Dominican Republic, Chile). By 1968, one million troops were deployed abroad, encircling a global network of 2,000 bases; CIA operators were in 60 countries, causing a spy epidemic in Hollywood, both a serious (Topaz, U, 1969) and not-so-serious strain (The Silencers, C, 1966).

But unlike all other Communist hot spots, Vietnam lasted the longest and proved indomitable. Around 1968, a sense of being overwhel...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Halftitle page

- Title page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Illustrations

- Foreword

- Part I Cultural Overview: The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1963–76

- Part II Business Practices

- Part III Technology

- Part IV Style

- Part V Censorship

- Part VI Genre

- Coda: Postmodern Hollywood, 1977

- Appendix: Hierarchical Order of Top Ten Box-Office Stars, 1963–76

- Bibliography

- Index of Films

- Index of Subjects