![]()

CHAPTER 1

Vagabond Value

Investor: Christopher Rees

Date of Birth: November 20, 1950

Hometown: Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic

Personal Web Site: www.tenstocks.com

Employment: Full-time investor, runs a subscription advisory

Passions/Pursuits: Workaholic, spends free time with wife and daughter

Investment Strategy: Deep value, special situations

Brokerage Accounts: TD Ameritrade

Key Strategy Metric: Tangible asset value

Online Haunts: www.marketocracy.com, www.valueinvestorsclub.com, www.10kwizard.com

Best Pick: Elan Corp., Up 143 percent

Worst Pick: Flag Telecom, Down 100 percent

Performance Since October 2000: Average annual return 25 percent versus 0.21 percent for the S&P 5001

Subsistence living is something that most of us never even consider. Living on the edge of poverty is, after all, the stuff of nightmares. It’s the downside we try never to think about.

But for nearly 30 years of his life Christopher Rees thought about subsistence living or “just getting by” nearly every day. Understanding his downside was a way of life. From age 19 to 49, Christopher Rees was a vagabond, moving around the globe from city to city, working in low-paying jobs, earning just enough to keep him going until his next stop. He became masterful at understanding how to stretch a dollar.

In fact, figuring out the bare minimums of survival became a religion for Rees. It is a lifestyle that also set the foundation for Chris Rees’s highly successful investment style.

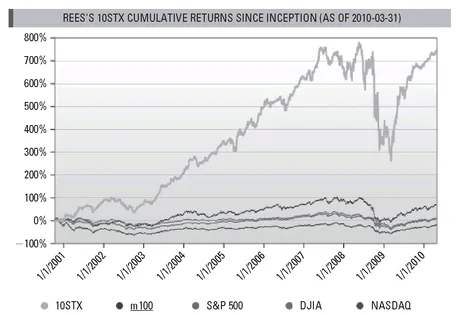

Since October 2000 Chris Rees’s Marketocracy.com portfolio (10STX) has logged an average annual return of 25 percent compared to less than 1 percent for the S&P 500 (see Figure 1.1). This impressive record incorporates a 40 percent loss during the financial meltdown of 2008. It would be difficult to find a skilled hedge fund pro with Rees’s stats. Among his closed stock positions, 89 percent have been winners.

Figure 1.1 Chris Rees versus the Market

Note: Returns are after all implied fees including 5c/share transaction fees; SEC feeds; management and administration fees of 19.5 percent.

Source: Marketocracy.com; data as of March 31, 2010.

Central to Rees’s investment strategy is figuring out what a company’s true net worth is. That means stripping out all of the fluff that is prevalent on CPA-certified corporate balance sheets.

Tangible asset value, real earnings, and debt levels are what Rees obsesses about. Just as he did during his vagabond days, he wants to know the bare minimums for a company’s survival so he can determine the risk he faces investing in a stock. Chris Rees wants to know the downside—the worst case. And if a stock is selling at 50 percent of what he reckons its value is, then he buys. Rees’s motto is taken right from the pages of Warren Buffett’s playbook. Simply, “Don’t lose money.”

Tangible Tactics

In a connected, always-on world where time is a precious resource and complexity and multitasking have become a way of life, Chris Rees is an unapologetic heretic.

He simply will not abide by this lifestyle, and this attitude infuses into his investment strategy. Life has a slower, simpler pace in the Dominican Republic where Rees resides. Temperatures rarely get below 70 degrees Fahrenheit, and the heat and humidity make siestas a way of life. It is a culture where patience is a prerequisite and “mañana” may be the most common refrain.

Simplicity is also a virtue for Rees, and when it comes to investing, Rees’s objective is to have only 10 stocks in his portfolio at any one time. This is not unlike other famous “deep value” investors like Warren Buffett and hedge fund managers Seth Klarman of Baupost Group and David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital.

These legendary value managers run concentrated portfolios. The idea is to own stocks as though they are businesses and to have a deep knowledge of all aspects of the companies’ operations, potential prospects, and pitfalls.

Strategy Tip

Though financial advisors lecture clients on the importance of diversification, many of the most successful investors like Chris Rees manage concentrated portfolios with relatively few holdings. Warren Buffett once said, “Diversification is protection against ignorance. It makes little sense for those who know what they are doing.”

Says Rees, “I’m a one-man show. There’s only one brain in this office. I know investment managers, and I see them on the TV, they run a 200-stock portfolio. To me it’s simply nuts. I work a lot of hours because I love my work. But I don’t think you can follow more than 10 stocks well.”

Chris Rees says that he gets his ideas from a slew of sources and is reluctant to give specifics, but he clearly uses stock screening software and alert services from web sites like the old 10kwizard.com (now called Morningstar Document Research) and SecInfo.com to cull through official SEC filings for certain fundamental characteristics.

“I may be looking for one or two investments a year,” says Rees. “I’ve got a universe of 10,000-plus companies, so I’m throwing companies over my shoulder like a maniac. Anything that doesn’t sniff right is eliminated, until I finish up with one company.”

At the heart of Rees’s strategy is his extreme aversion to losing money, or protecting his downside. Says Rees, “My basic philosophy is that I don’t believe successful investing is about finding stuff that goes up. I think it’s about finding stuff that’s not going to go down.”

To this end Rees is obsessive about determining a company’s tangible asset value, also known as its tangible book value. In conversation he sometimes refers to it as liquidation value.

Tangible asset value is defined as a company’s assets minus its liabilities. However, deducted from those assets are the fuzzy things that tend to inflate the number such as “goodwill,” which might measure the value of brands acquired during an acquisition. Another intangible asset that Rees might deduct is his estimation for obsolete inventory. In general, Rees is looking for companies that are selling at a price that is significantly lower than his estimation of its tangible asset value per share.

Strategy Tip

Rees cautions investors not to confuse his tangible asset value with the book value figures that are commonly quoted on dozens of web sites, including Yahoo Finance. Book value can be inflated by intangibles like goodwill or obsolete inventory. “Book value is too dodgy, squishy,” says Rees.

The next thing Rees looks at when investigating a potential stock to buy is its balance sheet, or debt levels. “I don’t like debt. I don’t want anything to do with debt,” he says. “Any business, any CEO who loads up on debt, I’m not interested.” Rees mostly focuses on a company’s debt-to-equity ratio, which he says shouldn’t exceed 50 percent.

The last thing Rees looks at in his relatively simple strategy is earnings. “The company has got to be profitable or I have to see a pathway to profitability.” Rees often looks for turnarounds and other special situations. Thus if Rees likes the long-term prospects of a company that will lose money for the next several quarters, before turning profitable, Rees will discount its tangible asset value by a multiple of its losses.

Here’s a basic explanation of how Rees determines value. Say Rees finds a company with low debt and figures out that its tangible asset value is $5 per share. If his estimate for forward earnings per share was $0.10 he might apply a price-earnings multiple of 10 to that. That would amount to $1 of future earnings value, so Chris would simply add the two to get a $6 estimated fair value for the stock. He would then seek to purchase it at a 50 percent discount to that value, or $3. If the stock price was too high, he would simply move on to the next candidate.

As part of Rees’s “go anywhere” deep value strategy, he often seeks special situations where he believes the stock’s true potential is misunderstood. One such special situation he’s made a killing on is Elan Corp. (NYSE: ELN). Rees first became interested in the biotech company in 2005 after its multiple sclerosis drug Tysabri was abruptly pulled from the market. Apparently, one of the patients taking Tysabri died of a rare brain infection. Elan’s stock plummeted to $3 from $30.

Rees did some digging to find out that the medical records revealed that part of the problem revolved around the patient taking the drug in conjunction with other medications and that the problem patient had a compromised immune system.

“Shares were trading on emotion and misinformation. I was a buyer into the fear and panic, which wasn’t easy at the time,” says Rees. “I thought Tysabri would come back, perhaps with a stiffer label, but the risk/reward benefit to the patient was significant.” Rees bought Elan’s distressed shares starting in 2005 as it was recovering. Elan’s been a volatile stock ever since, and Rees has skillfully traded in and out of it.

According to Marketocracy, Elan has accounted for $2.7 million of the gains on Rees’s million dollar virtual portfolio, which had a total value of $8.3 million as of the beginning of 2010.

Of course not all of Rees’s picks have been homeruns like Elan. In late 2000 Rees bought into the distressed shares of Flag Telecom,2 an Indian company that was laying fiber-optic cable under the sea for countries in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. “I thought this was a valuable asset and it would stay out of bankruptcy. Even if it filed I thought there were enough tangible assets and cash for the common stock to be worth something.”

However, in 2001 Flag filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and common stockholders were wiped out. Rees learned a valuable lesson about distressed asset investing.

“I saw first hand how bankruptcy law is used and abused using the wonder of ‘fresh start’ accounting. So, my interest now is more in who is in bankruptcy currently and who is likely to emerge with ‘fresh start’ value. Bankruptcy investing is fascinating.” Indeed, Rees cites Wilbur Ross, the well-known billionaire bankruptcy investor, among his investing role models.

In late 2009, Rees bought the post-bankruptcy shares of commercial finance and leasing company CIT Group (NYSE: CIT) for about $25. As of April 2010 its stock had risen to $40.

Who Is Chris Rees?

Chris Rees was born in 1950 in Stony Stratford, England, a small picturesque town about 90 minutes northeast of London. Stony Stratford dates back to Roman times, but it’s best known for being the birthplace of the proverbial “cock and bull story.” In the eighteenth century, two of Stony’s pubs, the Cock and the Bull, were known to host travelers going between London and Liverpool who would gossip and tell outlandish tales. To this day Stony still hosts storytelling and humor festivals celebrating Cock and Bull’s legacy.

The “Saga of Chris Rees” certainly deserves a place in Stony’s colorful history. Rees’s start in life was tortured because as a young child he suffered from severe allergies and eczema. As he recalls it, he spent from ages 5 to 10 confined to a hospital. “I was basically getting eaten alive with eczema,” he says. “The strategy in those days was to take a five-year-old kid and spread-eagle him out on a bed, tying him to the four corners and basically leave him there,” quips Rees. “I made a decision that if I ever got out of that place, I was never going back. So I thought the best way of making sure of this was to get the hell out of Dodge, be an independent person.”

So upon being released from the hospital at age 10, Rees began dreaming of his departure from Stony Stratford. His teachers didn’t think much of him, and as he puts it he was pegged for a career in “shoveling horse manure onto loganberry plants.” The only subject he seemed to excel at was geography.

In the middle to late 1960s, when Rees was finishing up high school, British authorities decided that they would create a new planned city called Milton Keynes just a few miles from Stony that would house hundreds of thousands of city dwellers being overcrowded in London. Rees saw this as an opportunity to earn money for the “escape” he was planning. So Rees took up selling household appliances to builders and contractors developing the vast suburban...