![]()

Part I

Structure of the Bioenergy Business

![]()

1

Characteristics of Biofuels and Renewable Fuel Standards

Alan C. Hansen, Dimitrios C. Kyritsis and Chiafon F. Lee

1.1 Introduction

Liquid biofuels currently in commercial use comprise primarily ethanol-derived fuels, mainly from grain, sugarcane or sugar beet, and biodiesel produced from a variety of vegetable oils and animal fats. It is expected that, in the future, a greater diversity of primary raw materials for manufacturing renewable transportation fuels will be used, including an array of recycled materials. For example, ethanol production from cellulosic material is likely, as well as butanol production from grain and possibly also from cellulose. Furthermore, the use of hydrogenation-derived renewable diesel and gasoline from fats, waste oils, or virgin oils processed either pure or blended with crude oil using petroleum refinery or similar operations, is being explored as an alternative [1]. In addition, the conversion of biomass to liquid fuel via pyrolysis is receiving attention, as well as the production of alkanes from the hydrogenation of carbohydrates, lignin, or triglycerides. Although methane production from waste materials is already well established, its use as a biofuel for transportation remains marginal to this date. In the long term, hydrogen derived from biomass is considered as the ideal fuel, because its combustion yields zero carbon dioxide. However, there are several technical hurdles that will need to be circumvented before this vision becomes reality, including not only the production of hydrogen from renewable materials but also safe methods for the storage and transport of hydrogen fuels [2].

In this chapter, the characteristics of biofuels will be focused primarily on ethanol and biodiesel, although other biofuels will also be mentioned when comparing the key properties of these materials.

1.2 Molecular Structure

Although in general, petroleum-based fuels are a blend of a very large number of different hydrocarbons, biofuels may consist of pure single-component substances such as hydrogen, methane or ethanol; alternatively, as in the case of biodiesel, they may be a mixture of typically five to eight esters of fatty acids, the relative composition of which is dependent on the raw material source. This relatively finite number of fatty acid esters in biodiesel contrasts with the much broader and more complex range of hydrocarbons that exists in petroleum. In addition, these biofuels are typically blended with petroleum-based fuels. A primary factor that distinguishes fuel alcohols and biodiesel from petroleum-based fuels is the presence of oxygen bound in the molecular structure. Alcohols are defined by the presence of a hydroxyl group (−OH) attached to one of the carbon atoms. For example, the molecular structure of ethanol is C2H5OH, and that of butanol is C4H9OH. Butanol is a more complex alcohol than ethanol as the carbon atoms can form either a straight-chain or a branched structure, thus resulting in different properties. Butanol production from biomass tends to yield mainly straight-chain molecules.

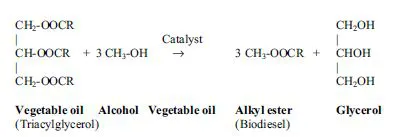

While straight vegetable oils have been used to power diesel engines, their viscosity is much greater than that of conventional diesel fuel. This is an important difference, as conventional engines have not been designed to be operated with relatively viscous fluids, and hence problems may be encountered when fuel vegetable oil is injected into the engine. In order to reduce the viscosity, one widely used method is to transesterify the vegetable oil or animal fat via a chemical reaction between the oil or fat and a mixture of an alcohol and a catalyst, as shown in Figure 1.1. The alcohol typically used in the reaction is methanol, thus creating methyl esters. It is worth noting that although ethanol (creating ethyl esters) and

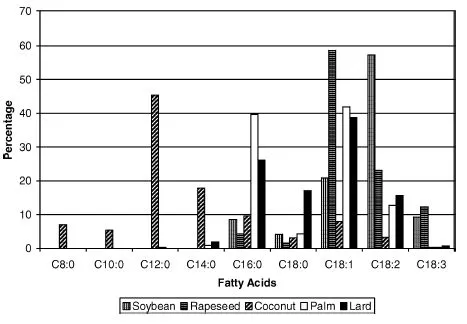

Vegetable oils and animal fats consist of a mixture of fatty acids with carbon chains of different lengths as well as different degrees of unsaturation (i.e., the number of double bonds that may exist in the fuel molecule). Figure 1.2 shows the fatty acid ester composition of selected source materials for producing biodiesel. Both the chain length and the degree of unsaturation have a major effect on the fuel properties of the esters in the biodiesel [5]. For example, an increase in chain length leads to a higher propensity for the fuel to self- ignite under conditions of high heat and pressure (this property is measured by the cetane number), while increasing the degree of unsaturation causes the cetane number rapidly to drop. However, the value of a higher cetane number with a longer carbon chain length is offset by increasing cloud and pour points; this results in the fuel gelling or solidifying at higher temperatures than would diesel fuel. These factors are discussed later in the chapter.

1.3 Physical Properties

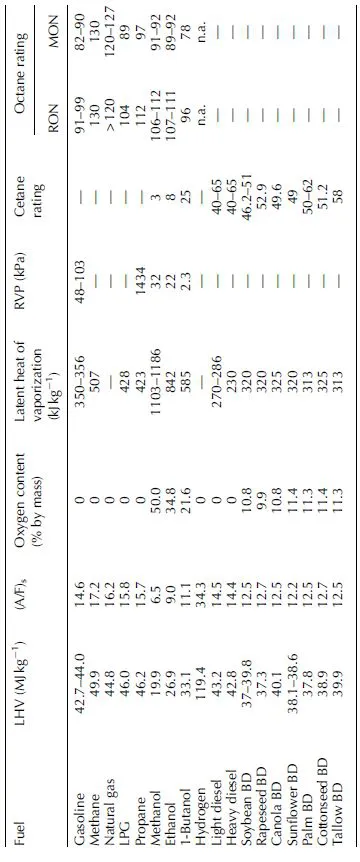

To a significant extent, engine manufacturers design their products based on expectations regarding the properties of the fuel to be used by the consumer. The introduction of biofuels such as ethanol and biodiesel has naturally led not only to a closer scrutiny of the standards of these new fuels, but also to attempts at characterizing their properties in detail. In turn, this information is used to modify engine control parameters in order to account for changes in fuel properties that could affect fuel atomization and combustion should the engine remained unchanged. This need for retrofit explains in part the resistance initially displayed by various automobile manufacturers to implement the use of ethanol. A comparison of the key properties of biofuels and petroleum-derived fuels is provided in Table 1.1. The physical properties of the fuel influence how well the fuel mixes with air and, as a result, its ability to combust. The mixing process relies on sufficient atomization of the fuel and its dispersion to occur either at the level of the intake of the engine or in the combustion chamber.

For most spark ignition (SI) engines, the fuel is injected into the inlet port immediately before the intake valve during the intake stroke. Mixing of the fuel and air is achieved as these two components enter the cylinder. Direct injection into the combustion chamber has also been introduced as a means to permit a much leaner overall combustion process. Notably, both processes require the fuel to be sufficiently volatile to facilitate mixing. The volatility of a fuel is determined by the Reid Vapor Pressure (RVP), a single digit measure of a fuel's propensity to evaporate. In the United States and other countries, the RVP is regulated for both conventional gasoline and ethanol blends to reduce evaporative emissions, as well as to prevent the occurrence of vapor locks in the fuel systems. Although ethanol has a much lower RVP than gasoline, it is well known that the addition of ethanol to gasoline raises the RVP, with a maximum being reached at about 10% ethanol.

The ability of the SI engine fuel to vaporize at engine start-up when cold is another very important characteristic, as it determines the ease with which the engine will start, as well as how it performs initially during vehicle idling, acceleration, or cruising. Ethanol has a much higher latent heat of vaporization than gasoline fuel (see Table 1.1), which means that more heat is required to cause fuel ethanol to vaporize as compared to conventional gasoline. This is the primary reason why a blending limit of 75–85% ethanol (E85) is specified by regulators, in order to ensure that there is a sufficient amount of an adequately volatile gasoline to vaporize, mix with the air, ignite, and thus allow the engine to start when cold. In this context, there have been recent indications that electrostatically assisted atomization may become a useful technology because of the relatively high electric conductivity of ethanol, which is five orders of magnitude higher than the one of hydrocarbons [20–23]. For example, engines have been developed and used in Brazil and Europe that run on E100; however, these engines either rely on gasoline being provided for cold starting, before switching to ethanol once the engine has warmed up, or they may use a specifically designed process for heating the fuel and the air in the manifold before the engine is started. One major advantage of combustion engines that run on E100 is their ability to tolerate the presence of up to 5% water in the ethanol fuel. This is important, as the cost of fuel ethanol production – particularly at the downstream purification step – is dramatically reduced when this specification is allowed. Notably, such relatively large amounts of water could not be accommodated in typical ethanol–gasoline blends as the ethanol would separate from the gasoline.

For diesel engines, the fuel atomization process is critical as there is very little time for the fuel to be injected into the combustion chamber, vaporized, mixed with air, and then chemically reacted and burnt. The physical characteristics that affect the atomization and fuel–air mixing process include: (i) fuel density; (ii) viscosity; and (iii) surface tension. These properties are strongly influenced by the fatty acid profiles of the biodiesel fuels, which in turn vary with the biomass raw material from which these fuels derive (see Figure 1.1) [15]. As compared to conventional diesel, biodiesel typically exhibits higher values for all of the characteristics listed above. For example, the density of biodiesel is approximately 7% higher than that of diesel fuel; this difference results in the biodies droplets penetrating deeper into the combustion chamber because of their higher momentum when injected.

Furthermore, compared to that of diesel fuel, the vapor pressure of biodiesel is much lower, which would be expected to have a significant influence on the spray evaporation process. Likewise, the heat of vaporization of biodiesel is lower at low temperatures, but it becomes higher at high temperatures. As the spray droplets are heated quickly during the vaporization process in the engine, it is expected that the evaporation of the biodiesel would be less efficient compared to petroleum-derived diesel fuel at those high temperatures

Surface tension is one of the most important properties in spray breakup and collision/ coalescence models. Empirical correlations have suggested that surface tension is a linear function of temperature, and therefore that it is relatively independent of the specific methyl ester mix that composes different varieties of biodiesel [6]. Consequently, at room temperature the surface tension of biodiesel is about the same as that of diesel. However, relative to conventional diesel the surface tension decreases more slowly with increasing temperatures, and thus becomes significantly higher than that of diesel at higher temperatures.

Compared to diesel, the heat capacity of biodiesel per unit mole is almost 50% higher at temperatures near these fuels' boiling points. However, when it is compared per unit mass – as used in the energy equation – the heat capacity of biodiesel is lower than that of diesel. This suggests that biodiesel droplets are heated faster than diesel droplets.

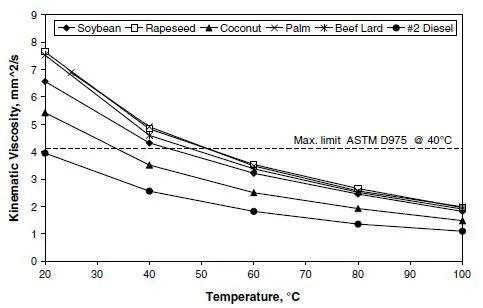

Liquid viscosity is an important parameter with regard to droplet atomization, drop internal flow, and wall film motion. Notably, the liquid viscosity of biodiesel is higher than that of diesel, especially at low temperatures where most of the atomization processes take place during the injection process in the engine. Therefore, it is to be expected that the atomization process will be affected by the viscosity difference. Figure 1.3 illustrates the differences in viscosity of biodiesel fuel made from the five raw materials shown in Figure 1.2, as compared to diesel fuel. Remarkably, all of these biodiesel fuels have higher viscosities; however, among the biodiesel fuels there is substantial variation caused by differences in fatty acid content.

Liquid thermal conductivity affects the heat transfer between the drop interior and the surface. Notably, the thermal conductivity of the biodiesel is slightly lower than that of the diesel [6].

The vapor heat capacity of the fuel is an important parameter that influences the thermal energy balance and temperature distribution of gas mixtures surrounding the spray drops, which in turn affects the transient heat transfer from the surrounding gas mixture to the drop surface. This is particularly important when the fuel drops rapidly vaporize so that the fuel–air mixture become richer. The vapor heat capacity of biodiesel is slightly lower than that of the diesel [6].

The transport properties of the vapor phase – that is, diffusivity, viscosity, and thermal conductivity – can all be estimated for biodiesel mixtures. Typically, the diffusivity for biodiesel vapor is much lower than that for diesel by as much as a factor of 20. The viscosity of biodiesel vapor is about 60% higher than that of diesel, while its thermal conductivity is about 30% lower than that of diesel [24].

Recent studies using multidimensional spray and combustion modeling have been conducted to investigate the effects of varying the fuel's physical properties on the spray and combustion characteristics of diesel-engines when these are operated using various biodiesel fuels [17, 18, 25–28]. The properties of typical biodiesel fuels that have been used in these studies, and the simulation results obtained, are compared with those of conventional diesel fuels. The sensitivity of the computational results to individual physical properties is also investigated by changing one property at a time. Exploitation of these results provide a guideline on the desirable characteristics of blended fuels. The properties investigated in Refs [17,18] included: (i) liquid density; (ii) vapor pressure; (iii) surface tension; (iv) liquid viscosity; (v) liquid thermal conductivity; (vi) liquid specific heat; (vii) latent heat; (viii) vapor specific heat; (ix) vapor diffusion coefficient; (x) vapor viscosity; and (xi) vapor thermal conductivity. The results suggest that the intrinsic physical properties of each of these fuels significantly impact spray structure, ignition delay and burning rates in a wide range of engine operating conditions. Moreover, these observations support the view that there is no single physical property that dominates the differences of ignition delay between diesel and biodiesel fuels. However, the most impactful of these characteristics seem to be liquid fuel density, vapor pressure, and surface tension. This latter observation can perhaps be ascribed to the importance of these parameters on the atomization, spray, and mixture preparation processes.

The spray atomization model thus developed, and which is used to model the breakup of fuels in diesel engines, relies heavily on the physical properties of the fuels being analyzed. As described earlier, significant differences exist in density, viscosity, surface tension and thermal conductivity between diesel and biodiesel fuels. Using this model and the fatty acid profiles of the source oils for biodiesel (as shown in Figure 1.2), the physical properties and critical temperature of soybean, coconut, palm, and lard biodiesels have been predicted. It is particularly noteworthy that these properties differ considerably between each of the biodiesel fuels analyzed. Moreover, a recent study has shown the effect that these differences have on fuel vaporization [6]. Due to its lower boiling point and critical temperature, coconut biodiesel shows a tendency to vaporize faster than any of the other pure biodiesel fuels when injected under engine-like conditions. The biodiesel fuels that behave most like pure conventional diesel include palm and lard biodiesel. Computed spray structures also demonstrate a relationship between atomized droplet diameter and fuel vaporization. Significant differences in the spray and vaporization between diesel–biodiesel blends of B2 (2% biodiesel: 98% diesel), B5 and B20 have also been demonstrated. These blends were modeled using the spray code including multicomponent fuel effects [17, 29–43]. At low blend percentages, such as B2 and B5, simulations for the biodiesel blends predict vaporization similar to that of diesel fuel. However, as the blend percentage increases to more than 5%, the fuel vapor mass is shown to decrease. The vapor mass composition is also affected by the blend percentage and lower volatility of biodiesel. The diesel fuel blends have a lower overall spray tip penetration than pure biodiesel; this characteristic is partially due to differences in molecular weights and densities of the fuels.

Another important characteristic of diesel fuels is their ability to retain liquid properties under cold weather conditions. On the other hand, when ambient temperatures are low enough, some hydrocarbons in diesel fuel begin to solidify, thereby inhibiting the flow of fuel from the storage tank to the fuel injection pump via the filter system. Such a property is represented by the cloud point and cold filter plugging point (CFPP), for which biodiesel fuels generally have higher temperatures; this makes...