eBook - ePub

Structural Materials and Processes in Transportation

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Structural Materials and Processes in Transportation

About this book

Lightness, efficiency, durability and economic as well as ecological viability are key attributes required from materials today. In the transport industry, the performance needs are felt exceptionally strongly. This handbook and ready reference covers the use of structural materials throughout this industry, particularly for the road, air and rail sectors. A strong focus is placed on the latest developments in materials engineering. The authors present new insights and trends, providing firsthand information from the perspective of universities, Fraunhofer and independent research institutes, aerospace and automotive companies and suppliers.

Arranged into parts to aid the readers in finding the information relevant to their needs:

* Metals

* Polymers

* Composites

* Cellular Materials

* Modeling and Simulation

* Higher Level Trends

Arranged into parts to aid the readers in finding the information relevant to their needs:

* Metals

* Polymers

* Composites

* Cellular Materials

* Modeling and Simulation

* Higher Level Trends

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Metals

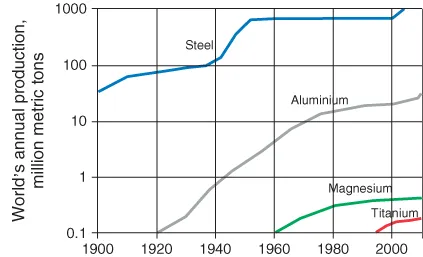

Metals belong to the eldest engineering materials of the humankind. The history can be traced back to the Copper Age when metallic products were firstly made of native metals. However, in contrast to natural materials, such as wood or stone, native metals were very rare. The rising needs of metallic products implied the invention and control of metallurgical processes, such as ore smelting and casting. In the period of the Bronze Age (2200–800 BC), when copper was firstly alloyed with tin, followed by the Iron Age (1100–450 BC), when advanced smelting and working techniques were introduced, the cornerstones for the industrial production were put in place. Since the beginning of the industrial production in the late eighteenth century, the demand for metals has been increased steadily (see Figure P1.1) [1]. The rapid technological development has led simultaneously to today's alloys and production processes. Nowadays, metals are spread in all technical applications of human life. The present means of transportation would have been inconceivable without metals.

Figure P1.1 World's annual production during the last century (following [1]).

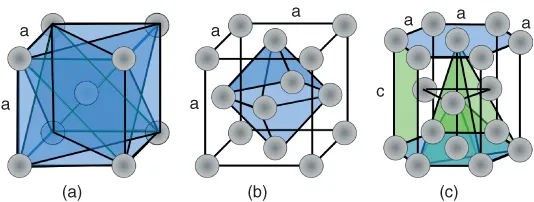

On microscale, metals are characterized by a crystalline structure. Electrons of the outer shell being freely movable between the atomic cores keep the crystal together. The electron's free mobility is responsible for both the high electrical and thermal conductivity of metals. Furthermore, the formation of close atomic packing within the crystal [2] enables a ductile atomic sliding under mechanical shear load. The siding proceeds on the densely packed planes along the close packed directions without changing the bonding conditions. The spatial arrangement of these sliding planes is shown in Figure P1.2. The number of sliding systems is the product of the number of sliding planes and the number of close packed sliding directions. While body centered cubic (BCC) and face centered cubic (FCC) structures, which can be found in ferritic steel and aluminum alloys exhibit respectively 12 and more systems for atomic sliding, the number of sliding systems in hexagonal crystal structures, which are typical for magnesium and α-titanium alloys, is dependent on the c/a ratio of the unit cell. Besides three basal sliding systems, alloys with c/a below 1.63 exhibit up to nine additional pyramid and prism sliding systems. In polycrystals, a number of more than five enables any deformation [3]. This fact explains the outstanding plasticity of most metals and, consequently, their excellent workability.

Figure P1.2 Sliding planes of (a) body centered cubic (BCC), (b) face centered cubic (FCC), and (c) hexagonal crystal structure.

The mass and the diameter of atoms as well as how close atoms are packed determine the density of a material [2]. Metals with a density of below 5 g cm−3 belong to the class of light metals [4]. In this class, magnesium is the lightest metal with a density of about 1.74 g cm−3 followed by aluminum with 2.70 g cm−3, and titanium with 4.50 g cm−3. The density difference between the pure metal and its alloys are usually very low. With a density of 7.86 g cm−3, iron, as the base metal of steel, belongs to the class of heavy metals. Because of its very high Young's modulus, and the variety of technical and metallurgical means to reach highest strength properties, nevertheless, this metal is still among the materials being attractive for light-weight designs.

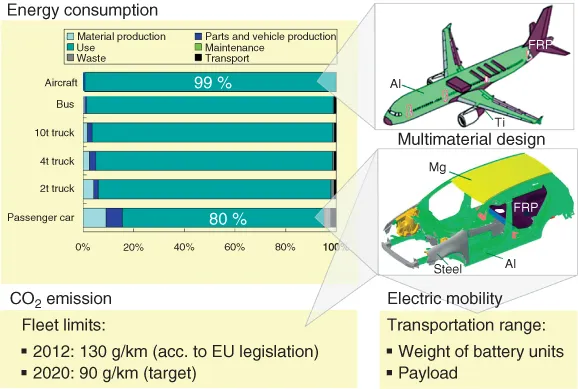

Weight reduction is an important subject for the transportation industry to improve their products' energy efficiency, particularly during the operation time. Low energy consumption benefits the reduction of CO2 emission and helps the electric mobility by increasing the transportation range. The main lightweight drivers are illustrated in Figure P1.3 [5].

Figure P1.3 Drivers of weight reduction and multimaterial design as a strategy for weight reduction (following [5, 7]).

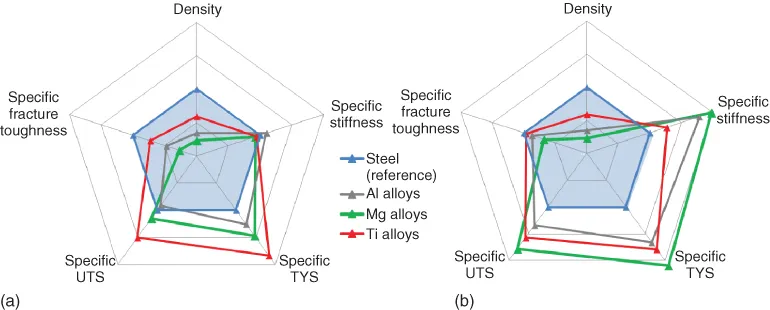

Generally, the potential of materials for weight savings can be evaluated by regarding their density-specific properties [6]. Compared to fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs), metallic materials, such as steel, aluminum, and magnesium alloys as well as titanium alloys, provide an excellent impact toughness, a good wear, and thermal resistance as well as a high life cycle fatigue along with moderate materials and processing costs and, furthermore, an outstanding recyclability.

Within this material class, steel is distinguished by its high specific tensile stiffness combined with a good fracture toughness and low material costs. Light alloys such as aluminum and magnesium alloys are characterized by high specific bending stiffness and strength values along with excellent compression stability. Titanium alloys are more expensive, but advantageous when, for example, a very high specific tensile strength and a good wet corrosion resistance is required. Figure P1.4 gives an overview of the mechanical properties for different loading conditions relative to those of steel as the reference material.

Figure P1.4 Density and relative mechanical properties of metals (a) for tension/compression load and (b) for bending/buckling load (reference: steel) (values according to [6]).)

However, owing to the ongoing need of weight reduction, alternative structural materials, such as FRP, penetrate more and more into transportation applications (see Figure P1.3). Compared to metallic materials, for example, carbon-fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs) are still very expensive, but on the other hand they exhibit specific strength and stiffness values, which are significantly higher than those of metallic materials. Consequently, effective weight reduction calls for advanced multimaterial designs (Figure P1.3) [7]. Thus, in order to ensure a cost efficient weight reduction, a strong position of metals is required. This necessitates a multidisciplinary approach that combines materials science and production technology with designing and dimensioning.

The following sections shall give an overview of recent advances in the development of steel, aluminum, and magnesium alloys as well as titanium alloys, which are intended for application in the transportation sector. Basically, the alloy development is closely related to process development, comprising a variety of production techniques associated with the development of advanced metallic products. Therefore, descriptions of selected process developments are also part of these sections.

References

1. Degischer, H.P. and Lüftl, S. (eds) (2009) Leichtbau–Prinzipien, Werkstoffauswahl und Fertigungsvarianten, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim, ISBN: 978-3-527-32372-2, p. 80.

2. Ashby, M.F. and Jones, D.R.H. (2005) Engineering Materials 1, 3rd edn, Butterworth–Heinemann as an imprint of Elsevier, Oxford, ISBN: 978-0750663809.

3. Gottstein, G. (2010) Physical Foundations of Materials Science, 1st edn, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, ISBN: 978-3-642-07271-0.

4. Roos, E. and Maile, K. (2004) Werkstoffkunde für Ingenieure: Grundlagen, Anwendung, Prüfung, Springer-Verlag, ISBN: 978-3540220343.

5. Kasai, J. (2000) Int. J. Life Cycle Assess., 5 5316.

6. Ashby, M.F. (1999) Materials Selection in Mechanical Design. Butterworth-Heinemann Verlag, Oxford, ISBN: 978-0750643573.

7. Goede, M., Dröder, K., Laue, T. (2010) Recent and future lightweight design concepts–The key to sustainable vehicle developments. Proceedings CTI International Conference–Automotive Leightweight Design, Duisburg, Germany, November 9–10, 2010.

1

Steel and Iron Based Alloys

1.1 Introduction

As a consequence of global warming the demand for transport vehicles with lower emissions and higher fuel efficiency is increasing [1]. Reduction of travel time and CO2 emissions per passenger is also noticed in transport applications. Different methods have been utilized to improve the fuel economy, which is also demanded by the governments. For instance, the Obama administration in the United States has recently proposed a law requiring a 5% increase in fuel economy during 2012–2016 and the development of the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) to obtain an average automotive fuel efficiency of 35.5 miles per gallon by 2016 [1–3]. Since the development of new power generation system in hybrid-electric vehicles is expensive, new technologies aim to improve fuel economy through improving aerodynamics, advanced transmission technologies, engine aspiration, tires with lower rolling resistance, and reduction of vehicle weight [4]. Usage of new kinds of lightweight steels in vehicle design for automotive and transport applications is of great importance nowadays for enhancing safety, improving fuel economy, and reducing lifetime greenhouse gas emissions.

Sheet and forged materials for transport applications require both high strength and formability. High strength allows for the use of thinner gauge material for structural components, which reduces weight and increases fuel efficiency [5]. High strength also improves the dent resistance of the material, which is esthetically important. Another advantage of higher strength material is improved passenger safety due to the higher crash resistance of the material. Therefore, the high strength material must be formable to allow economical and efficient mass-produced automotive parts.

New tools and technologies such as modeling and simulations are being innova...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Part I: Metals

- References

- 1: Steel and Iron Based Alloys

- 2: Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys

- 3: Magnesium and Magnesium Alloys

- 4: Titanium and Titanium Alloys

- Part II: Polymers

- 5: Thermoplastics

- 6: Thermosets

- 7: Elastomers

- Part III: Composites

- References

- 8: Polymer Matrix Composites

- 9: Metal Matrix Composites

- 10: Polymer Nanocomposites

- Part IV: Cellular Materials

- References

- 11: Polymeric Foams

- 12: Metal Foams

- Part V: Modeling and Simulation

- 13: Advanced Simulation and Optimization Techniques for Composites

- 13:An Artificial-Intelligence-Based Approach for Generalized Material Modeling

- 15: Ab Initio Guided Design of Materials

- Part VI: Higher Level Trends

- 16: Hybrid Design Approaches

- 17: Sensorial Materials

- 18: Additive Manufacturing Approaches

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Structural Materials and Processes in Transportation by Dirk Lehmhus,Matthias Busse,Axel Herrmann,Kambiz Kayvantash in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.