- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

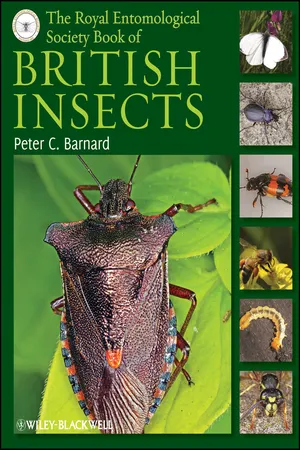

The Royal Entomological Society Book of British Insects

About this book

This book is the only modern systematic account of all 558 families of British insects, covering not just the large and familiar groups that are included in popular books, but even the smallest and least known. It is beautifully illustrated throughout in full colour with photographs by experienced wildlife photographers to show the range of diversity, both morphological and behavioural, among the 24,000 species.

All of the 6,000 genera of British insects are listed and indexed, along with all the family names and higher groups. There is a summary of the classification, biology and economic importance of each family together with further references for detailed identification. All species currently subject to legal protection in the United Kingdom are also listed.

The Royal Entomological Society is one of the oldest and most prestigious of its kind in the world. It is the leading organisation for professional entomologists and its main aim has always been the promotion of knowledge about insects. The RES began its famous Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects in 1949, and new works in that series continue to be published. The Royal Entomological Society Book of British Insects has been produced to demonstrate the on-going commitment of the RES to educate and encourage each generation to study these fascinating creatures.

This is a key reference work for serious students of entomology and amateur entomologists, as well as for professionals who need a comprehensive source of information about the insect groups of the British Isles they may be less familiar with.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 General introduction

- PART 1: Entognatha

- PART 2: Insecta – ‘Apterygota’

- PART 3: Palaeoptera

- PART 4: Polyneoptera

- PART 5: Paraneoptera

- PART 6: Endopterygota

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app