![]()

1

Introduction to the Mediterranean mountain environments

Ioannis N. Vogiatzakis

1.1 Introduction

Mountains are present in all continents, latitude zones and principal biome types, accounting for more than 20% of the Earth's terrestrial surface (Beniston, 2000). They come in all shapes and forms and are even present on islands, oceanic and continental. The northern hemisphere hosts most of the world's mountain areas, whereas the highest concentration of high mountains is in Central and southern Asia. The harsh conditions of mountain environments, including high altitude steep slopes, and extreme weather, result in them being regarded as hostile regions and therefore less inhabited and productive areas. However, they are still home to 20% (1.2 billion) of the world's human population and have special spiritual, cultural and sacred significance for over one billion people worldwide (Price, 2004). Isolation in geological and historic times has resulted in mountains acting as biological and cultural laboratories.

Worldwide mountains encompass a great diversity of topographic, climatic, biotic and cultural elements and therefore provide a range of ecosystem services (MEA, 2005).

Mountains are an important source of water, energy and biological diversity. Furthermore, they are a source of such key resources as minerals, forest products and agricultural products and of recreation. As a major ecosystem representing the complex and interrelated ecology of our planet, mountain environments are essential to the survival of the global ecosystem.

Agenda 21, Chapter 13, ‘Managing Fragile Ecosystems: Sustainable Mountain Development’

Table 1.1 Research goals for mountains according to the Glochamore initiative (Björnsen Gurung, 2005)

| Climate | To develop consistent and comparable regional climate scenarios for mountain regions, with a focus on Mountain Biosphere Reserves |

| Land use change | To monitor land use change in mountain regions using methods that are consistent and comparable |

| Cryosphere | To predict the areal extent of glaciers under different climate scenarios |

| Water systems | To determine and predict water balance and its components, particularly run-off and water yield of mountain catchments (including wetlands and glaciers) under different global change scenarios |

| Ecosystem functions and services | To predict the amount of carbon and the potential yield of timber and fuel sequestered in forests under different climate and land use scenarios |

| Biodiversity | To assess current biodiversity and to assess biodiversity changes |

| Hazards | To predict changes of lake systems and incidence of extreme flows in terms of frequencies and amounts, under different climate and land use scenarios |

| Health | To understand the current and future distribution and intensity of climate-sensitive health determinants, and predict outcomes that affect human and animal health in mountain regions |

| Mountain economies | To assess the value of mountain ecosystem services and how that value is affected by different forms of management |

| Society and global change | To understand the environmental, economic, and demographic processes linking rural and urban areas in mountain regions, as well as those leading to urbanization, peri-urbanization and metropolization |

Half of the human population depends on mountains, while globally about half of the mountain area is under some sort of human land use (Körner and Ohsawa, 2005). Despite the harsh environmental conditions, human presence in mountain areas has a long history, going back millennia for some parts of the world such as the Mediterranean Basin. The wealth of goods and services that mountains provide come at an extra cost for human communities due to the limitations on the exploitation of these resources compared to other environments. The major environmental issues that mountains face worldwide include, other than dynamic geophysical processes (e.g. North Atlantic Oscillation and volcanic activity), anthropogenic ones such as pollution, land use change and human-induced climatic change (Beniston, 2000). A recognition of mountains in the policy agenda came in 1992 at the UN Conference on Environment and Development, which resulted in the establishment of other initiatives – Mountain Partnership, Mountain Forum: Glochamore (Global Change in Mountain Regions) – and received the attention of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Price, 2007). These are attempts to outline the scientific challenges (i.e. threats and opportunities) that the mountains face worldwide for future development (Table 1.1). Globally there are many drivers that affect environmental change although at present the principal ones are climate, land use change, and their interactions. In a mountain environment context, environmental change will affect the capacity of landscapes to continue to provide services not only for resident populations but also for dependent populations beyond the mountains’ extent. Changes in temperature and precipitation regimes, and the frequency of extreme events, will have severe repercussions on the physical character and on the biological and human communities of mountain areas. Glaciers, snow cover, water storage and flow, are unique features of mountainous areas; however, any changes affecting them will in turn impact on lowland areas. The range of environmental conditions present in mountain regions has resulted in mountains playing a significant part in the conservation of global biodiversity. Environmental changes will affect not only the species present, but also ecosystem functions such as biochemical cycling and habitat provision. Climate changes, through the alteration of the frequency of extreme events, may pose a threat to life and property in mountain regions, create new health hazards for humans and their domestic animals, and cause severe impacts on mountain economies and livelihoods. Land use, one of the major drivers of change globally, is subject to external forces such as climate and global markets. The response to change will not only require increased understanding of how drivers operate in mountain environments but also the appropriate institutional capacities to react.

Although many textbooks and specialized books have been written about mountain environments (e.g. Gerrard, 1990; Barry, 1992; Funnell and Parish, 2001; Parish, 2002) there has been only one so far for the Mediterranean mountains (McNeill, 1992). This first chapter is an introduction to the mountain environments of the Mediterranean Basin. It will set the scene and place the mountains of the basin in the global context while at the same time providing a brief overview of the various subjects illustrated in this book, and explain the organization of its content.

1.2 Setting the scene

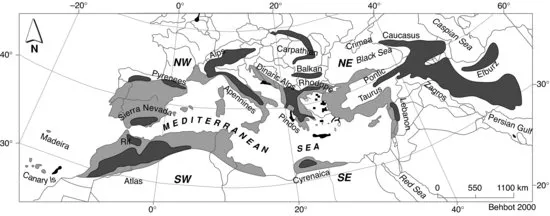

Unquestionably mountains constitute the backbone of the whole Mediterranean region, including the largest islands in the basin (Figure 1.1). McNeill (1992, p. 1) in the only book dedicated to the Mediterranean mountains to be published so far, wrote: ‘The beauty of the Mediterranean mountains is in way a sad one. Skeletal mountains and shell villages dot the upland areas of the Mediterranean world, dominating the physical and social landscape.’ Imposing massifs run from North to South such as the Pindos in Greece, the Apennines in Italy, and the Dinarids in Balkans, West to East such as the Atlas Mountains extending over 3500 km from North Morocco to Tunisia, and dominate the landscapes of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Cyprus and Crete.

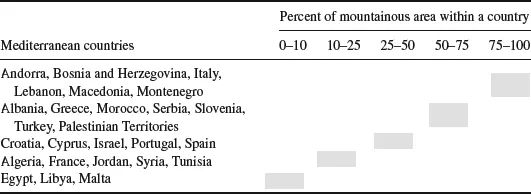

Definitions about what constitutes a mountain vary and include topography, climate, vegetation, constraints on agriculture, or length of growing seasons (Gerrard, 1990; Kapos, 2000). A working definition is the one by Price (1981): ‘An elevated landform of high local relief, e.g. 300 m (1000 ft), with much of its surface in steep slopes, usually displaying distinct variations in climate and associated biological phenomena from its base to its summit.’ According to this definition an attempt to answer the question how large is the mountain area globally came up with the figure of 24.3% of total land area. The figure excludes the major plateau areas, and all land area outside Antarctica (Kapos et al., 2000). Mediterranean mountains cover some 1.7 million km2, equivalent to 21% of the combined surface area of all the countries concerned, and are home to 66 million people, representing 16% of the region's total population. Mountains occupy more than 50% of land in many Mediterranean countries (Table 1.2), seven of which are among the top 20 mountainous countries in the world. Morocco is an example of such country with a high percentage of mountainous land, where four major mountain ranges – the Rif, the Middle Atlas, the High Atlas and the Anti-Atlas – occupy 15% of its territory (Radford et al., 2011)

Table 1.2 Percentage of mountainous land within Mediterranean countries (Regato and Salman, 2008)

The delineation of the Mediterranean mountains is a more complex issue since it is directly related to the delineation of the Mediterranean area itself, which has been the topic of debate for decades. For the latter the criteria used have been floristic, climatic or bioclimatic (see Blondel et al., 2010). In a recent attempt at an environmental classification for the whole of Europe (Metzger et al., 2005), Mediterranean mountains were recognized as separate entities influenced by both the Mediterranean zone they are situated in, and a distinct mountain climate. The class ‘Mediterranean mountains’ encompasses low and medium mountains in the northern part of the basin and high mountains in the southern part. As Blondel et al. (2010) state, ‘there is no satisfactory answer to the question of what is a “Mediterranean mountain”, as compared to a mountain range simply marking a regional boundary.’ Taking into account the various delineations and classification schemes applied in the Mediterranean Basin, we broadly distinguish three mountain categories in this book from the heart to the periphery of the basin:

- Mountains at the very heart of the Mediterranean either due to their geographical position or their moderate altitude, including the Sierra Nevada, Cyrenaica, mountains of the Peloponnese and those on the islands of Sicily, Corsica, Crete and Cyprus.

- Mountains that are considered outside the influence of, or on the periphery of the Mediterranean, for example the Alps, Mercantour, the North Dinarids, and the North of Anatolia (Ozenda, 1975).

- Mountains included in the various delineations of the Mediterranean area that have biotic affinities to the basin, such as the mountains of the Canary islands.

This book focuses on the first category, since extending this volume to cover all the massifs associated with the Mediterranean Basin would be a huge task. However, there are limited references to the other two categories (see Chapters 3 and 4).

Mediterranean mountains exhibit many similarities in their biotic, ecological, physical and environmental characteristics but also significant differences. They have always been inextricably linked to their surroundings, providing, for example, cities and coastal areas with invaluable resources including water, timber and even labour (Benoit and Comeau, 2005). Relief in the Mediterranean is affected more by erosional processes than by glacial abrasion, compared to other European mountains; Mediterranean mountains receive more precipitation compared to the surrounding lowlands and are sources of various important rivers. In general, mountains in the northern part of the Mediterranean are lower than those in the southern Mediter...