eBook - ePub

Lead Optimization for Medicinal Chemists

Pharmacokinetic Properties of Functional Groups and Organic Compounds

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lead Optimization for Medicinal Chemists

Pharmacokinetic Properties of Functional Groups and Organic Compounds

About this book

Small structural modifications can significantly affect the pharmacokinetic properties of drug candidates. This book, written by a medicinal chemist for medicinal chemists, is a comprehensive guide to the pharmacokinetic impact of functional groups, the pharmacokinetic optimization of drug leads, and an exhaustive collection of pharmacokinetic data, arranged according to the structure of the drug, not its target or indication. The historical origins of most drug classes and general aspects of modern drug discovery and development are also discussed. The index contains all the drug names and synonyms to facilitate the location of any drug or functional group in the book.

This compact working guide provides a wealth of information on the ways small structural modifications affect the pharmacokinetic properties of organic compounds, and offers plentiful, fact-based inspiration for the development of new drugs. This book is mainly aimed at medicinal chemists, but may also be of interest to graduate students in chemical or pharmaceutical sciences, preparing themselves for a job in the pharmaceutical industry, and to healthcare professionals in need of pharmacokinetic data.

This compact working guide provides a wealth of information on the ways small structural modifications affect the pharmacokinetic properties of organic compounds, and offers plentiful, fact-based inspiration for the development of new drugs. This book is mainly aimed at medicinal chemists, but may also be of interest to graduate students in chemical or pharmaceutical sciences, preparing themselves for a job in the pharmaceutical industry, and to healthcare professionals in need of pharmacokinetic data.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lead Optimization for Medicinal Chemists by Florencio Zaragoza Dörwald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Organic Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

Chapter 1

The Drug Discovery Process

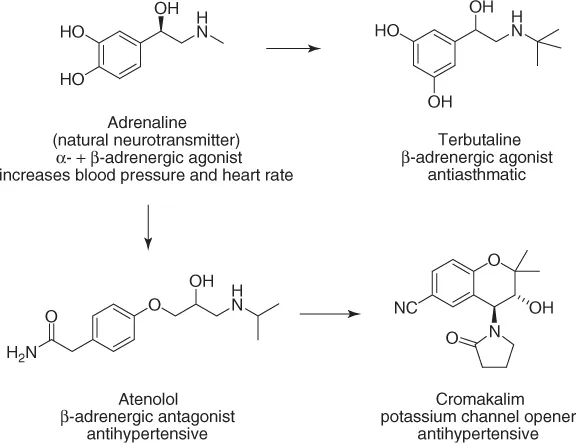

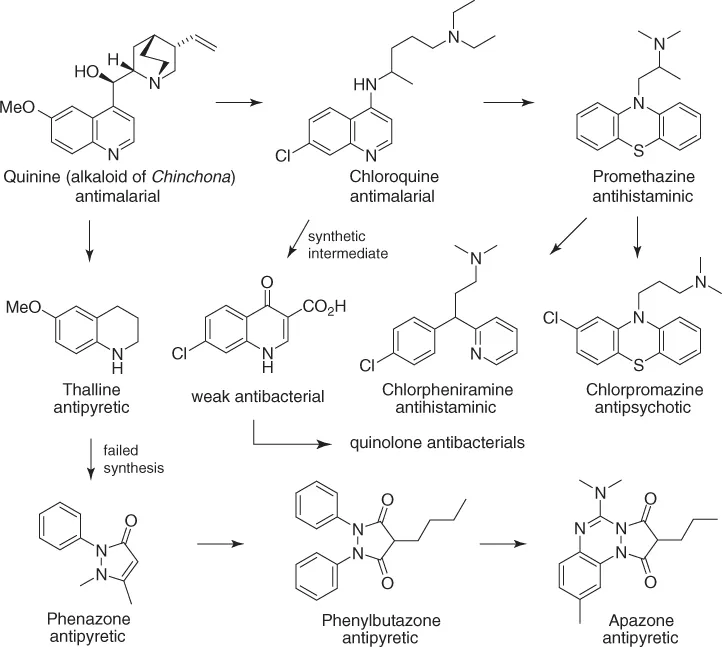

Drugs are compounds that interact selectively with certain proteins in the human body and, thereby, suppress or activate biochemical pathways or signal transmission. Although the structures of modern drugs hardly allow to guess their origins, these were mostly natural products, discovered empirically, and used for centuries [1]. While synthesizing and evaluating new structural analogs of known hormones or natural drugs, new therapeutic applications often emerged. A fruitful starting point for the development of new drugs has in fact often been an old drug [2]. Illustrative examples of “drug evolution” are shown in Scheme 1.1.

Scheme 1.1 Examples of the development of new drugs from old drugs.

To initiate a drug discovery program with hormones, natural products, or old drugs as leads has a number of advantages: the biochemical concept is already proven (the compound “works”), the target is “druggable,” and, importantly, the lead structure has acceptable or at least promising PK/ADME (pharmacokinetics/absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) properties; otherwise, it would not work.

High-throughput screening of compound collections only rarely provides leads for new drugs [3]. Notable exceptions include the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, benzodiazepines, and sulfonamide antibacterials. These important drug classes resulted from testing drug-unrelated chemicals.

New proteins are constantly being discovered, and many of them are potential targets for therapeutic intervention. It must be kept in mind, though, that only few drugs have been successfully developed from scratch, starting with a biochemical hypothesis. The odds for succeeding are higher with a lead that works in vivo or by optimizing or exploiting a side effect of an old drug.

Today, the development of a new drug usually comprises the following stages:

1. Discovery A target protein is selected, for example a receptor or an enzyme. If no lead structure is available, high-throughput screening of suitable, leadlike compounds may yield some weak ligands (hits). Systematic structural modification of these, supported by in vitro assays, may provide a lead, that is, a compound with an unambiguous dose–response relationship at the target protein. Further structural modifications aim at improving potency at the target, selectivity (low affinity to other proteins), water solubility, pharmacokinetics (PK, oral bioavailability, half-life, CNS penetration, etc.), therapeutic index (LD50/ED50), and general ADMET properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity). In addition to in vitro assays, the medicinal chemist will need guidance by more time- and compound-consuming in vivo pharmacology.

2. Preclinical development Once a development candidate has been chosen, the following steps will be initiated: chemical scale-up of the selected compound, formulation, stability studies, more detailed metabolic, toxicological, and PK studies (only in animals, typically rodents, dogs, pigs, or primates).

3. Clinical development

| Phase I | Healthy volunteers; determination of the suitable dose |

| for humans | |

| Phase II | First studies with a small group of patients |

| Phase III | Extended clinical trials |

Thus, the fateful selection of a development candidate, which will either fail or succeed during the expensive preclinical or clinical development, is already taken in the discovery phase. Success in drug development is, therefore, primarily dependent on the medicinal chemist, on his ability to design and prepare the compound with the desired biological properties. No matter how hardworking and talented the members of the preclinical and clinical development team are, if the medicinal chemist has not delivered the right compound, the whole project will fail. And the later the recognition of the failure, the larger the costs.

Thus, pharmaceutical companies should allocate significant resources to the hiring and training of their medicinal chemists.

1.1 Pharmacokinetics–Structure Relationship

During the discovery phase of a new drug, two different, mutually independent sets of properties of the compound must be optimized: (i) potency and selectivity at the target protein and (ii) ADME and toxicity. The most critical ADME/PK parameters are as follows:

- Plasma half-life (t1/2) The time required for the plasma concentration of a drug to drop by 50%. A constant half-life means that the rate of elimination of a drug is a linear function of its concentration (first order kinetics). This is never exactly the case, and t1/2 will usually increase as the concentration of the drug declines.

- Oral bioavailability (F) The fraction of a drug that reaches systemic circulation after oral dosing. Oral bioavailability is determined by dividing the area under the curve (AUC) for an oral dose by the AUC of the same dose given intravenously. A low F means that either the drug is not absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or that it undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver.

- Plasma protein binding (pb) Hydrophobic compounds will bind unspecifically to any hydrophobic site of a protein. For this reason, high-throughput screening often yields hydrophobic hits (which are difficult to optimize and should be abandoned). Plasma proteins, such as albumin or α-glycoproteins, may also bind to drugs and thereby reduce their free fraction in plasma, their renal excretion, their ability to cross membranes (also the blood–brain barrier (bbb)), and their interaction with other proteins (metabolizing enzymes, the target protein). Binding to plasma proteins also prevents highly insoluble compounds from precipitating upon iv dosing and helps to distribute such drugs throughout the body. The half-life of peptides may be increased by preventing their renal excretion through enhanced binding to albumin. This can be achieved by acylating the peptide with fatty acids or other plasma protein binding compounds.Plasma protein binding is usually determined by equilibrium dialysis or ultrafiltration. Both techniques exploit the ability of certain membranes to be permeable to small molecules but not to proteins or protein-bound small molecules. The clinical relevance of plasma protein binding has been questioned [4].

- Volume of distribution (V) Amount of drug in the body divided by its plasma concentration. The volume of distribution is the volume of solvent in which the dose would have to be dissolved to reach the observed plasma concentration. Compounds with small volumes of distribution (i.e., high plasma concentration) are often hydrophilic or negatively charged molecules that do not diffuse effectively into muscle and adipose tissue. Compounds strongly bound to plasma proteins will show small volumes of distribution as well. Hydrophobic and/or positively charged molecules, however, readily dissolve in fat and interact strongly with the negatively charged cell surfaces (phospholipids) and, often, have large volumes of distribution (i.e., low plasma concentrations). Experimental and computational methods have been developed to estimate the volume of distribution in humans [5]. The typical volumes of body fluids are as follows:

Plasma 0.04–0.06 l kg−1 Blood 0.07 l kg−1 Extracellular fluid 0.15 l kg−1 Total body water 0.5 l kg−1 The “ideal” volume of distribution depends on the targeted half-life and pharmacological activity. For antibiotics or antivirals directed toward intracellular pathogens, a high tissue distribution (large volume of distribution) would be desirable. For short-acting anesthetics or antiarrhythmics or for compounds with a low safety margin, smaller volumes of distribution may enable a better control of drug plasma levels. - Clearance (CL) The rate at which plasma is freed of drug, the remainder of the drug diluting into the freed volume. If a constant concentration C of a drug is to be attained, the infusion rate must be CL ×C. CL is related to other PK parameters: CL = dose/AUC = ln2 × (V/t1/2). The liver blood flow in humans is about 25 ml min−1 kg−1.

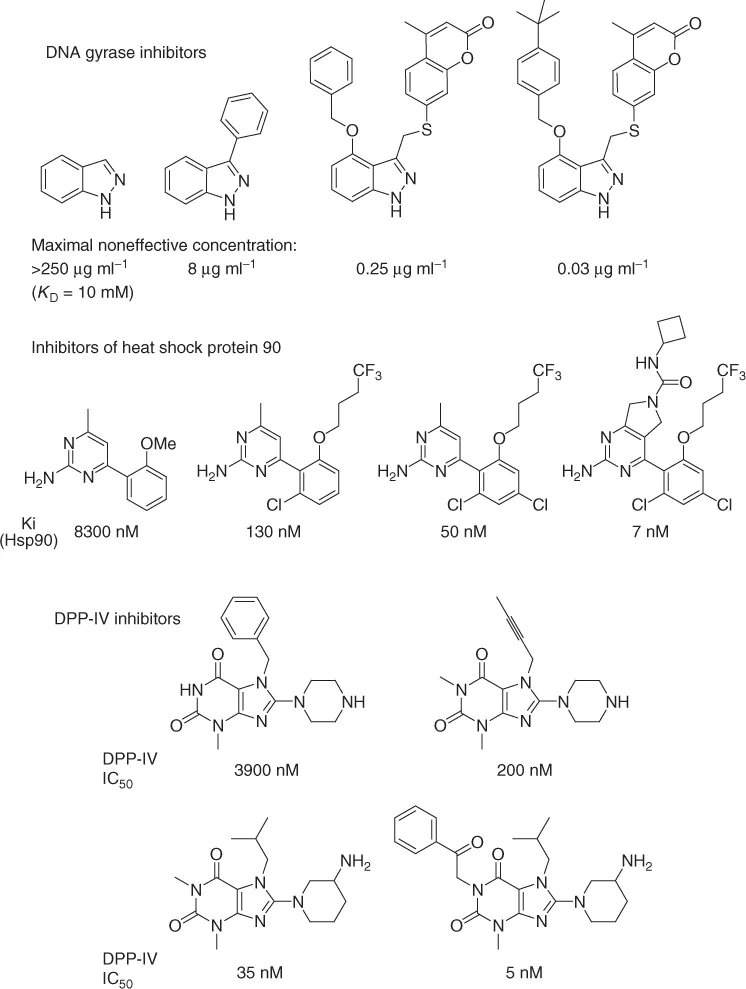

With the aid of high-throughput in vitro assays, potency and selectivity at a given target protein can often be rapidly attained. The most promising strategy for ligand optimization is to start with a small, hydrophilic (i.e., leadlike, not druglike) compound identified by screening leadlike compounds at high concentrations (leads are usually smaller, more hydrophilic, and less complex than drugs and show lower affinity to proteins). Then, potency and selectivity is enhanced by systematically introducing lipophilic groups of different shapes at various positions of the hit [6]. Numerous examples of such optimizations have been reported; three examples are shown below (Scheme 1.2 [6c, 7], see also Chapter 72; discovery of losartan).

Scheme 1.2 Examples of the enhancement of binding affinity of small molecules to specific proteins.

Unfortunately, the structure–activity relationship (SAR) resulting from such examples is of little use for medicinal chemists, as these only hold for specific target pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Introduction

- Glossary and Abbreviations

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: The Pharmacokinetic Properties of Compound Classes

- Index