eBook - ePub

A Primer on Stroke Prevention and Treatment

An Overview Based on AHA/ASA Guidelines

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Primer on Stroke Prevention and Treatment

An Overview Based on AHA/ASA Guidelines

About this book

Society-sanctioned guidelines are valuable tools, but accessing key information can be a daunting task. This book illuminates a clear path to successful application of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines. Organized for fast reference, this new volume helps practitioners improve patient care.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Primer on Stroke Prevention and Treatment by Larry B. Goldstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Cardiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I Overview Topics

1 Stroke Epidemiology

EXAMPLE CASE

A 45-year-old right-handed African-American man examination is notable only for a right upper-motor residing in central North Carolina has a history of neuron pattern facial paresis and 3/5 strength in his hypertension and presents with right-sided weakness right arm and leg with depressed right-sided deep without a language impairment and visual or sensory tendon reflexes and a right plantar-extensor deficits. He also has a 50-pack-year history of response. A brain CT scan obtained 4 hours after cigarette smoking. His examination revels a body symptom onset was normal. An EKG followed by a mass index (BMI) of 35, a blood pressure of transthoracic echocardiogram showed left ventricular 180/95 mm Hg, a regular pulse, no cervical bruits, hypertrophy (LVH). and no cardiac murmur. His neurological examination is notable only for a right upper-motor neuron pattern facial paresis and 3/5 strength in his right arm and leg with depressed right-sided deep tendon reflexes and a right plantar-extensor response. A brain CT scan obtained 4 hours after symptom onset was normal. An EKG followed by a transthoracic echocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH).

MAJOR POINTS

- Although overall stroke mortality rates have been rapidly declining, consistently higher rates remain among African-Americans (particularly between ages 45 and 65) and Southerners.

- Risk factors influencing stroke incidence can be stratified into two tiers:

- The graying of America is likely to have a major impact on the absolute number of stroke events in the next half-century, with an anticipated dramatic increase in the number of stroke events particularly among elderly women.

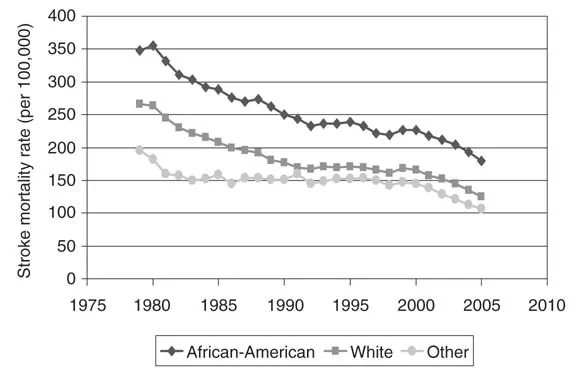

Stroke mortality and its disparities

There are few US national data describing stroke incidence, and as a result, most of what is known about stroke epidemiology focuses on mortality rates. The age–sex-adjusted stroke mortality rates by race-ethnic group for the United States between 1979 and 2005 are shown in Figure 1.1. This figure reflects the remarkable successes and failures in stroke. During this brief 26-year period, stroke mortality has declined by 48.4% for African-Americans, by 52.9% for whites, and by 45.5% for other races [1] – a decline in a chronic disease that is simply striking. Along with similar reductions in heart disease mortality, this decline was acknowledged as one of the “Ten Great Public Health Achievements” of the 20th century (the only two achievements that were listed for a specific disease) [2].

This same figure, however, underscores one of the great failures in the 20th century – striking disparities by race. Using the year 2000 age standard, in 1979, African-Americans had an age-adjusted stroke mortality rate that was 30.8% higher than whites, whereas other races had a rate that was 26.7% below whites. This is in contrast to 2005, when African-Americans had stroke mortality rates 43.0% higher than whites, a relative increase of 39.6% ([43.0– 30.8]/30.8) in the magnitude of the racial disparity in stroke deaths. This increase in stroke mortality among African-Americans persists despite the Healthy Persons 2010 goals (one of the guiding documents for the entire Department of Health and Human Services) having as one of its two primary aims “to eliminate health disparities among segments of the population, including differences that occur by gender, race or ethnicity, education or income, disability, geographic location, or sexual orientation” [3].

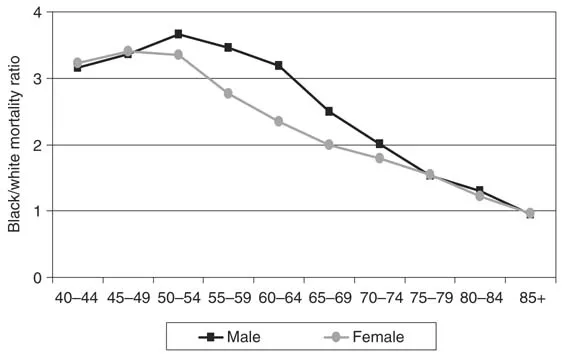

This figure obscures another disturbing pattern. The African-American–white differences in stroke mortality rates are three to four times (300–400%) higher between the ages of 40 and 60. These are attenuated with increasing age to become approximately equivalent above age 85 (see Figure 1.2)[4]. Data from the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study suggest that this excess burden of stroke mortality is primarily attributable to higher stroke incidence rates in African-Americans (rather than case fatality), and is uniformly shared between first and recurrent stroke, as well as between isch-emic and hemorrhagic (both intracerebral and sub-arachnoid) stroke subtypes; all have incidence race ratios between 1.8 and 2.0 [5,6].

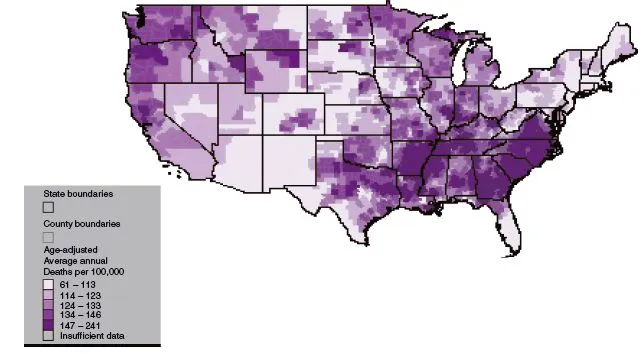

Another great disparity in stroke mortality is the “stroke belt” – a region in the southeastern United States with high stroke mortality that has persisted since at least 1940 (see Figure 1.3 [7]). Whereas the overall magnitude of geographic disparity is between 30% and 50%, this map shows that specific regions (such as the “buckle” region of the stroke belt along the coastal plain of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) have stroke mortality rates well over twice those of other regions. There are as many as 10 published hypothesized causes of this geographic disparity [8,9], but the reason for its existence remains uncertain. Finally, depending on sex and age strata, the magnitude of the southern excess stroke mortality is between 6% and 21% greater for African-Americans than for whites [10]. The example patient is at a higher risk of stroke and stroke mortality compared with Americans of other race-ethnic groups because he is an African-American and because he resides within the stroke-belt region of the country.

Fig. 1.1 Age-adjusted (2000 standard) stroke mortality rates for ages 45 and older, shown for African-American, white, and all other races. Data were retrieved from the Centers for Disease Control Wonder System [1], with ICD-9 codes 430–438 for years 1979–1998, and ICD-10 codes I60 to I69 for years 1999–2005.

Fig. 1.2 African-American-to-white age-specific stroke mortality ratio for 2005 for the United States [4].

Fig. 1.3 Geographic pattern of stroke mortality rates between 1991 and 1998 for US residents aged 35 and older. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Stroke Atlas. www.cdc.gov/DHDSP/library/maps/strokeatlas/index.htm.

Stroke risk factors

The current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Primary Stroke Prevention Guidelines provides a comprehensive review of potential stroke risk factors with an extensive listing of references (offering a total of 572) [11]. A list of more than 30 separate risk factors and conditions reviewed in these guidelines is summarized in Table 1.1, along with classifications on the support for treatment and the level of evidence regarding the role of the factor in modifying stroke risk. Although the table is comprehensive, the goal of this section is to provide a more focused discussion within a framework that may be quickly considered by practicing clinicians. Any attempt to reorganize the listing provided in the guidelines should not be interpreted as minimizing the importance of any factor in an individual patient, but rather as helping to set priorities in a resource-limited environment.

The foundation of the approach to organize risk factors is to consider efforts to establish “risk functions” for stroke in which the factors are considered as independent predictors of stroke risk taken from the more comprehensive list. Although reported over 15 years ago, the most well known of these risk assessments is from the Framingham Study cohort in which independent stroke predictors included age, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes mellitus, current smoking, established coronary disease (any one of myocardial infarction [MI], angina or coronary insufficiency, congestive heart failure, or intermittent claudica-tion), atrial fibrillation, and LVH [12]. It is striking that this list of independent predictors was confirmed by perhaps the second best known of these risk functions, produced from the Cardiovascular Health Study, which included precisely the same list of risk factors (plus additional measures of frailty) [13]. Not accounting for age as a disease risk factor and considering systolic blood pressure and use of antihypertensive medications as one factor, that these two risk functions were concordant with the independent risk factors for stroke strongly suggests these six factors as “first-tier” risk factors for stroke (see Table 1.2). The example patient has a history of hypertension, an additional, modifiable, “first-tier” stroke risk factor.

Table 1.1 Summary of recommendations from the American Heart Association Guidelines for primary stroke prevention

| Nonmodifiable |

| 1 Age |

| 2 Sex |

| 3 Low birth weight |

| 4 Race ethnicity |

| 5 Genetic factors (IIb, C) |

| Well-documented and modifiable risk factors |

| 1 Hypertension (I, A) |

| 2 Cigarette smoking (I, B) |

| 3 Diabetes (I, A) |

| 4 Atrial fibrillation (I, A) |

| 5 Other cardiac conditions |

| • Left ventricular hypertrophy (IIa, A) |

| • Heart failure (IIb, C) |

| 6 Dyslipidemia (I, A) |

| 7 Asymptomatic carotid stenosis (I, C) |

| 8 Sickle-cell disease (I, B) |

| 9 Postmenopausal hormone therapy (III, A) |

| 10 Diet and nutrition |

| • Sodium intake (I, A) |

| • Healthy diet (DASH) (I, A) |

| • Fruit and vegetable diet (IIb, C) |

| 11 Physical inactivity (I, B) |

| 12 Obesity and body fat distribution (I, A) |

| Less well-documented or potentially modifiable risk factors |

| 1 Metabolic syndrome (see individual components) |

| 2 Alcohol abuse (IIb, B) |

| 3 Drug abuse (IIb, C) |

| 4 Oral contraceptive use (III, B/C) |

| 5 Sleep-disordered breathing (IIb, C) |

| 6 Migraine (ratings not provided, but considered “insufficient” to recommend a treatment approach) |

| 7 Hyperhomocysteinemia (IIb, C) |

| 8 Elevated lipoprotein (a) (IIb, C) |

| 9 Elevated lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (absence of evidence) |

| 10 Hypercoagulability (absence of evidence) |

| 11 Inflammation (IIa, B) |

| 12 Infection (absence of evidence) |

| 13 Aspirin for primary stroke prevention (III, A) |

DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

Attempts were made to classify each potential risk factor on two scales (shown in the table as Roman numerals and letters). First, each was classified by the strength of evidence for a treatment approach into strata: I) conditions for which there is evidence for and/or general agreement that the procedure or treatment is useful and effective; IIa) conditions for which there is conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of a procedure or treatment, but the weight of evidence or opinion is in favor of the procedure or treatment; IIb) conditions for which there is conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of a procedure or treatment, and the usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence or opinion; and III) conditions for which there is evidence and/or general agreement that the procedure or treatment is not useful/effective and in some cases may be harmful. The second classification was on the level of evidence into strata: A) data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials; B) data derived from a single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies; or C) consensus opinion of experts.

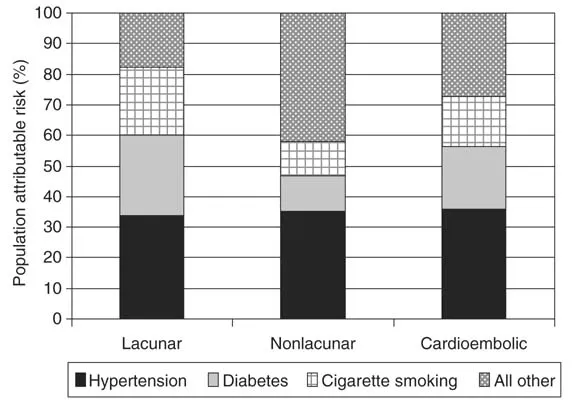

The “population attributable risk” (the proportion of stroke events attributable to specific risk factors) is a product of both the magnitude of the impact of a risk factor and its prevalence in the at-risk population, and provides important insights to the contributions of these first-tier risk factors. The population attributable risk for major stroke types was recently reported from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (Figure 1.4)[14] showing that the combination of hypertension, diabetes, and cigarette smoking contributes the great majority of risk for lacunar (82%), nonlacunar (58%), and car-dioembolic (73%) stroke. The substantial contribution of these three risk factors to stroke risk is underscored by the population attributable risk in the American Heart Association (AHA)/American Stroke Association (ASA) guidelines paper [11], which, while based on different studies, sums to more than 100% (i.e., more than 100% of the risk of stroke is attributed to different causes). The guidelines statement suggests that hypertension alone contributed between 30% and 40% of stroke risk, cigarette smoking between 12% and 18%, and diabetes between 5% and 27% [11]. Clearly, these three risk factors could be called “the big three” of the first tier. In addition to being an African-American residing in the stroke belt with a history of hypertension, the example patient smokes cigarettes, further increasing his stroke risk. His clinical syndrome is consistent with a “lacunar” syndrome.

Table 1.2 A proposed structure for consideration for modifiable stroke risk factors

| 1 First-tier factors |

| • The “big three” factors (based on population attributable risk) |

| a. Hypertension |

| b. Diabetes |

| c. Cigarette smoking |

| • Other first-tier factors |

| a. Heart diseases |

| b. Atrial fibrillation |

| c. Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| 2 Second-tier factors |

| • Risk factors for risk factors. Examples: |

| a. Obesity and body fat distribution |

| b. Physical inactivity |

| • Risk factors important to control (regardless of stroke risk). |

| Examples: |

| a. Dyslipidemia |

| b. Metabolic syndrome |

| • Risk factors important in special populations |

| a. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis |

| b. Postmenopausal hormone therapy |

| c. Sickle-cell condition |

| • Risk factors with a smaller effect or questionable effect (others) |

Fig. 1.4 Population attributable risk for major stroke subtypes of stroke from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study for the “big three” risk factors and all others (including second-tier risk factors). Adapted from data available in Ohira et al. [14].

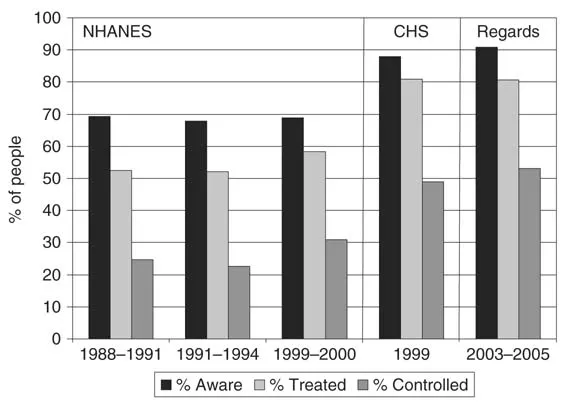

Fig. 1.5 Awareness, treatment, and control of blood pressure.

CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; REGARDS, Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke.

CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; REGARDS, Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke.

As a clinician, it is not only important to treat specific risk factors in individual patients, but it is also important to think at the level of a group of patients (e.g., a practice) and allocate resources where they can have the greatest impact. Importantly, treatment approaches that will lead to substantial reductions in the overall burden of stroke would need to particularly target this “big three” cluster of risk facto...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Classification of Recommendations and Level of Evidence

- Part I Overview Topics

- Part II Special Topics

- Other Statements Published in 2008

- COI Table

- Index