![]()

Chapter One

When I went to business school back in the late seventies (note to my kids: that's the 1970s!), we learned one important thing about stock market investing. It was simply this: there are so many smart people out there, you can't outsmart them. In other words, thousands of intelligent, knowledgeable people buy and sell stocks all day long, and as a result, stock prices reflect the collective judgment of all these smart people. If the price of a stock is too high, these smart people will sell until the price comes down to a lower, more reasonable price. If a stock price is too low, smart people will go in and buy until the stock's price rises to a fair level. This whole process happens so quickly, we were taught, that in general stock prices correctly reflect all currently available information. If, indeed, prices are accurate, there is no use in trying to “beat the market.” In other words, according to my professors, the only way I was going to find a bargain-priced stock was by luck.

Naturally, I didn't listen (which, unfortunately, made this no different from most of my other classes).

But flash forward a few decades and now I'm the professor. Each year I teach a course in investing at a top Ivy League business school. The students are clearly smart, accomplished, and dedicated. In short, they are the best and the brightest. But every year for the last fourteen, I have walked into class on the very first day and told my students something eerily familiar and very disturbing. I tell them this: “Most of your peers and predecessors who learn about investing at business schools across the nation and beyond will go out into the real investing world and try to ‘beat the market.’ And almost all of them will do one thing in common—fail!”

How can this be? If brains and dedication aren't the deciding factors in determining who can be a successful investor, what are? If an Ivy League business school education doesn't determine investment success, what does? Are we really just back to where we started? After decades of investment experience and learning, were my business school professors right after all? The only way to beat the market is by luck?

Well, not exactly. I'm still glad I didn't listen to my professors. Investors can beat the market. It's just that becoming a successful investor doesn't have much to do with being one of the best and the brightest. It doesn't have much to do with attending a top business school (though being stupid with no degree isn't much help, either). Success also has nothing to do with an ability to master the economic and business news that bombards us each day. And success can't be found by following the hundreds of expert opinions offered on television, in newspapers, and in investment books. The secret to beating the market, as unlikely as it sounds, is in learning just a few simple concepts that almost anyone can master. These simple concepts serve as a road map, a road map that provides a way through all the noise, confusion, and bad directions. A road map that most smart MBAs, investment professionals, and amateur investors simply don't have.

And that makes sense. If being smart or having a business degree were all it took, there would be many thousands of individual and professional investors with great long-term investment records. There aren't. The answer, it seems clear, must lie elsewhere.

But that leaves us with another problem. If the answer is really as simple as I appear to be saying, in effect pretty much anyone can sign up to beat the market. How can that be? Why, if it's so simple, aren't there thousands of successful investors out there? This whole thing is starting not to make sense.

Well, the truth is it does make sense. The concepts needed to be a successful stock market investor are simple. Most people can do it. It's just that most people won't. Understanding why they won't (or don't) is the crucial first step to becoming a successful investor. Once we understand why most others fail, we can fully appreciate the simple solution.

But this understanding comes with a price. We need to start from the beginning and build our case step by step. Understanding where the value of a business comes from, how markets work, and what really happens on Wall Street will lead us to some important conclusions. It will also lead small investors (and even not-so-small investors) to some very good investment choices.

What I tell my students on the first day of class is still true. Most individuals, MBAs, and professionals who try to beat the market—won't. But you can. Let's see why.

![]()

Chapter Two

I was having a bad week. In no particular order: I dropped out of law school (understandably, my parents weren't too thrilled), broke up with my girlfriend (okay, she broke up with me, but at the time I had no idea that was actually a good thing), locked my keys in the car—twice (once in the ignition with the engine still running and once in the trunk at 11 p.m. after a Yankees game in the Bronx—and as you probably know, everybody's a 24-hour locksmith but no one really works those 24 hours all in a row), and finally, went through a toll booth with no money (after a few eye rolls and since Guantánamo was not yet taking prisoners, they let me mail it in, with the stamp costing more than the actual toll).

Luckily, the true value of a life cannot be summed up by a single bad week or even a series of bad months but by the total of everything we do and accomplish over a period of many years. I bring this up not to relive the glory days of my youth (such as they were) but because if you want to learn how to be a good investor, you're going to have to have a good understanding of the concept of “value”—what it is and where it comes from. This is pretty important because the secret to successful investing is fairly simple: first figure out the value of something—and then pay a lot less. I'll repeat that: the secret to successful investing is to figure out the value of something—and then pay a lot less.

Benjamin Graham, the acknowledged father of security analysis, called this “investing with a margin of safety.” The larger the space between current price and calculated value, the larger our margin of safety. Graham figured that if unexpected events lower the value of our purchase or our initial valuation is mistakenly high, buying with a large margin of safety will still protect us from big losses.

That's all fine, but what is “value” and where does it come from? The corner candy store might have a great location and a booming business, and at a price of $150,000 that business might be a great investment. But buy that same candy store for $50 million, same great location, same booming business, and you've pretty much guaranteed yourself a terrible investment (and created a whole mystery about how you got the $50 mil in the first place). In short, if we invest without understanding the value of what we're buying, we'll have little chance of making an intelligent investment.

In the same way that one lousy week didn't end up defining the value of my entire life, it turns out that the value of a business doesn't have that much to do with what happens each week or each month. Rather, the value of a business comes from how much that business can earn over its entire lifetime. That can often mean many years (and by many, I mean twenty, thirty, or even more—we can't just be thinking about earnings over the next two or three). While figuring out the earnings of a business over the next thirty-plus years might sound like a pretty hard thing to do, we're going to try to do it anyway. We'll start with a simple example, and by chapter's end, we should have a pretty good understanding of how this whole value thing is supposed to work. (And once we start to understand value, there's no telling what we can accomplish in the rest of the book!)

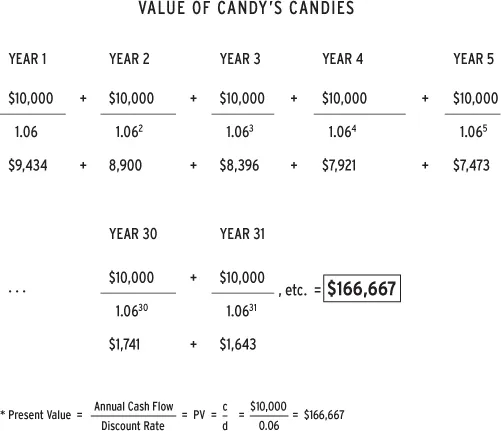

We'll even assume for the purposes of our simple example that we know (somehow) ahead of time what the earnings of our business will be over the next thirty years and beyond. To make it even simpler, we'll assume that the business in question, Candy's Candies, will earn $10,000 each year for the next thirty-plus years. So let's see what happens.

Intuitively, we know that collecting $10,000 each year for the next thirty years is not the same as receiving all $300,000 today. If we had that $300,000 right now, one easy thing we could do is to put it in the bank and then earn some interest on our deposit. The bank could take our money, pay us a few percent each year in interest, and then lend that money out to other people or businesses and collect a higher interest rate than they pay us. Everybody wins. By the time thirty years go by, we'd have a lot more than the original $300,000 from all the interest we collected. But, of course, Candy's Candies only earns $10,000 each year, and we'll have to wait thirty years to collect all $300,000. So let's break it down and see what thirty-plus years of earning $10,000 per year are really worth to us today.1

Let's assume for the sake of simplicity that we are the proud owners of Candy's Candies, that we collect all of our earnings at the end of each year, and that a bank will pay us 6 percent each year on any deposits that we make. So let's start by figuring out the value today of collecting that first $10,000 in profits from our new business at the end of the first year and then we'll go from there.

We know that collecting $10,000 a year from now is not the same as having that $10,000 today. If we had the $10,000 right now, we could put it in the bank and earn 6 percent interest. At the end of the first year, we'd have $10,600, not merely $10,000. So the $10,000 we collect a year from now is worth less than $10,000 in our hands today. How much less? Pretty much the 6 percent less that we didn't get to earn in interest. The math looks like this: $10,000 one year from now discounted by the 6 percent we didn't get to earn is $10,000 ÷ 1.06, which equals $9,434. (Another way to look at it: if you had $9,434 today and deposited it in the bank at 6 percent, you would have $10,000 at the end of one year.)

So the value of our first year's earnings from Candy's Candies is worth $9,434 to us in today's dollars. How about the second year's earnings? What are those worth to us in today's dollars? Well, two years from now, we will be collecting another $10,000 in profits from our ownership of our candy business. What is $10,000 that we won't receive for two years worth today? Well, it works out to $8,900 ($10,000 ÷ 1.062). If we had $8,900 today and deposited it in the bank at 6 percent, we would have $10,000 by the end of the second year. And so the value today of our first two years of earnings from Candy's Candies is $9,434 + $8,900, or $18,334. (This is getting really exciting!)

I won't go through the next twenty-eight-plus years, but the exercise looks something like this:

So earning $10,000 a year for the next thirty-plus years turns out to be worth about $166,667 today. Using these simple assumptions, we just figured out something incredibly important. Candy's Candies, a business guaranteed to earn us $10,000 each year for the next thirty-plus years or so, is worth the same as having $166,667 cash in our pocket today! Now, here's the hard part. If we could be guaranteed that all of our assumptions were correct and someone offered to sell us Candy's Candies for $80,000, should we do it?

Well, here's another way to ask the same question. If someone offered to give us $166,667 right now in exchange for $80,000, should we do it? Given all of our assumptions, the answer is easy: of course we should do it! This is an incredibly important concept. If we can really figure out the value of a business like Candy's Candies, investing becomes very simple! Remember, the secret to successful investing is to figure out the value of something and then—pay a lot less! In fact, it couldn't be simpler: $166,667 is a lot more than $80,000—case closed.

Of course, there's one little problem. I made the “figuring out the value of something” part a bit too easy. How? Let me count the ways.

Remember, I told you ahead of time what the earnings of Candy's Candies were going to be each year for the next thirty-plus years. But will earnings actually shrink over those years? Will they grow? Will Candy's Candies even be around in another thirty years? In practice, predicting so far into the future is pretty hard to do. In addition, many businesses are actually more complicated than the corner candy store. In fact, forget thirty years—it turns out that Wall Street analysts are actually pretty bad at predicting earnings for even the next quarter or the next year. Are you really going to trust my predictions about what earnings will be over the next thirty years? (Remember, I can't remember the keys or the toll money, and I'm not even a lawyer!)

So here's the problem. Since no one really knows for sure what earnings will be over the next thirty-plus years, whatever we use for estimated earnings during that time is just going to be a guess. Even if this guess is made by a very smart, informed “expert,” it will still be a guess. There will always be a chance that this guess is off, sometimes by a lot. So when we figure out the value of our business, we're going to have to assume that there is risk to our estimate of earnings for that business. The amount of earnings we expect to receive from owning that business over the next thirty-plus years will almost always be uncertain. Obviously, we'll make our best guess about what those earnings will be. But those earnings will always be far from a sure thing.

So here's the question. What would you pay more for—a guaranteed $10,000 a year for the next thirty-plus years, or a best guess of collecting $10,000 a year for the next thirty-plus years? It's pretty clear that a guarantee is worth more than a guess. In practice, investors discount the price they will pay for future earnings that are based only on estimates. If there is no guarantee that you will actually collect that $10,000 after the first year of owning Candy's Candies, you will probably pay less for those earnings than if they were guaranteed. In our simple example where next year's earnings of $10,000 were guaranteed, we discounted that payment by 6 percent, reflecting the fact that we had to wait a year to collect our $10,000. Now, with only an estimated $10,000 coming in at the end of the first year, we will pay less.

How much less? That's not exactly clear, but we would certainly discount that hoped-for $10,000 by more than the 6 percent we used when the $10,000 was guaranteed—maybe ...