- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Optimal Learning

About this book

Learn the science of collecting information to make effective decisions

Everyday decisions are made without the benefit of accurate information. Optimal Learning develops the needed principles for gathering information to make decisions, especially when collecting information is time-consuming and expensive. Designed for readers with an elementary background in probability and statistics, the book presents effective and practical policies illustrated in a wide range of applications, from energy, homeland security, and transportation to engineering, health, and business.

This book covers the fundamental dimensions of a learning problem and presents a simple method for testing and comparing policies for learning. Special attention is given to the knowledge gradient policy and its use with a wide range of belief models, including lookup table and parametric and for online and offline problems. Three sections develop ideas with increasing levels of sophistication:

- Fundamentals explores fundamental topics, including adaptive learning, ranking and selection, the knowledge gradient, and bandit problems

- Extensions and Applications features coverage of linear belief models, subset selection models, scalar function optimization, optimal bidding, and stopping problems

- Advanced Topics explores complex methods including simulation optimization, active learning in mathematical programming, and optimal continuous measurements

Each chapter identifies a specific learning problem, presents the related, practical algorithms for implementation, and concludes with numerous exercises. A related website features additional applications and downloadable software, including MATLAB and the Optimal Learning Calculator, a spreadsheet-based package that provides an introduction to learning and a variety of policies for learning.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE CHALLENGES OF LEARNING

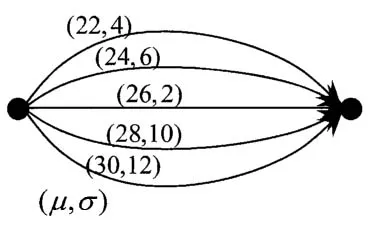

1.1 LEARNING THE BEST PATH

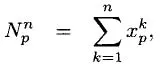

| = | initial estimate of the expected travel time on path p, |

| = | initial estimate of the standard deviation of the difference between  |

1.2 AREAS OF APPLICATION

Transportation

- Responding to disruptions - Imagine that there has been a disruption to a network (such as a bridge failure) forcing people to go through a process of discovering new travel routes. This problem is typically complicated by noisy observations and by travel delays that depend not just on the path but also on the time of departure. People have to evaluate paths by actually traveling them.

- Revenue management - Providers of transportation need to set a price that maximizes revenue (or profit), but since demand functions are unknown, it is often necessary to do a certain amount of trial and error.

- Evaluating airline passengers or cargo for dangerous items - Examining people or cargo to evaluate risk can be time-consuming. There are different policies that can be used to determine who/what should be subjected to varying degrees of examination. Finding the best policy requires testing them in field settings.

- Finding the best heuristic to solve a difficult integer program for routing and scheduling - We may want to find the best set of parameters to use our tabu search heuristic, or perhaps we want to compare tabu search, genetic algorithms, and integer programming for a particular problem. We have to loop over different algorithms (or variations of an algorithm) to find the one that works the best on a particular dataset.

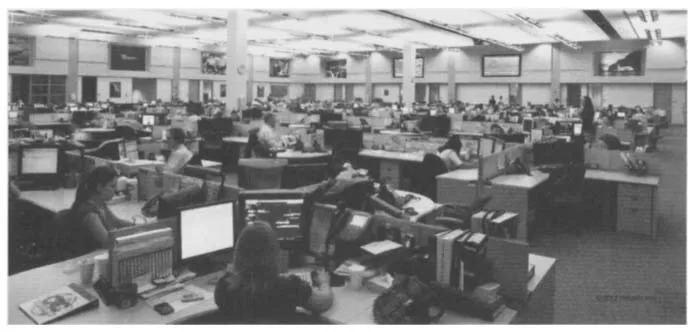

- Finding the best business rules - A transportation company needs to determine the best terms for serving customers, the best mix of aircraft, and the right pilots to hire1 (see Figure 1.2). They may use a computer simulator to evaluate these options, requiring time-consuming simulations to be run to evaluate different strategies.

- Evaluating schedule disruptions - Some customers may unexpectedly ask us to deliver their cargo at a different time, or to a different location than what was originally agreed upon. Such disruptions come at a cost to us, because we may need to make significant changes to our routes and schedules. However, the customers may be willing to pay extra money for the disruption. We have a limited time to find the disruption or combination of disruptions where we can make the most profit.

Energy and the Environment

- Finding locations for wind farms - Wind conditions can depend on microgeography - a cliff, a local valley, a body of water. It is necessary to send teams with sensors to find the best locations for locating wind turbines in a geographical area. The problem is complicated by variations in wind, making it necessary to visit a location multiple times.

- Finding the best material for a solar panel - It is necessary to test large numbers of molecular compounds to find new materials for converting sunlight to electricity. Testing and evaluating materials is time consuming and very expensive, and there are large numbers of molecular combinations that can be tested.

- Tuning parameters for a fuel cell - There are a number of design parameters that have to be chosen to get the best results from a full cell: the power density of the anode or cathode, the conductivity of bipolar plates, and the stability of the seal.

- Finding the best energy-saving technologies for a building - Insulation, tinted windows, motion sensors and automated thermostats interact in a way that is unique to each building. It is necessary to test different combinations to determine the technologies that work the best.

- R&D strategies - There are a vast number of research efforts being devoted to competing technologies (materials for solar panels, biomass fuels, wind turbine designs) which represent projects to collect information about the potential for different designs for solving a particular problem. We have to solve these engineering problems as quickly as possible, but testing different engineering designs is time-consuming and expensive.

- Optimizing the best policy for storing energy in a battery - A policy is defined by one or more parameters that determine how much energy is stored and in what type of storage device. One example might be, “charge the battery when the spot price of energy drops below x.” We can collect information in the field or a computer simulation that evaluates the performance of a policy over a period of time.

- Learning how lake pollution due to fertilizer run-off responds to farm policies - We can introduce new policies that encourage or discourage the use of fertilizer, but we do not fully understand the relationship between these policies and lake pollution, and these policies impose different costs on the farmers. We need to test different policies to learn their impact, but each test requires a year to run and there is some uncertainty in evaluating the results.

- On a larger scale, we need to identify the best policies for controlling CO2 emissions, striking a balance between the cost of these policies (tax incentives on renewables, a carbon tax, research and development costs in new technologies) and the impact on global warming, but we do not know the exact relationship between atmospheric CO2 and global temperatures.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CHAPTER 1: THE CHALLENGES OF LEARNING

- CHAPTER 2: ADAPTIVE LEARNING

- CHAPTER 3: THE ECONOMICS OF INFORMATION

- CHAPTER 4: RANKING AND SELECTION

- CHAPTER 5: THE KNOWLEDGE GRADIENT

- CHAPTER 6: BANDIT PROBLEMS

- CHAPTER 7: ELEMENTS OF A LEARNING PROBLEM

- CHAPTER 8: LINEAR BELIEF MODELS

- CHAPTER 9: SUBSET SELECTION PROBLEMS

- CHAPTER 10: OPTIMIZING A SCALAR FUNCTION

- CHAPTER 11: OPTIMAL BIDDING

- CHAPTER 12: STOPPING PROBLEMS

- CHAPTER 13: ACTIVE LEARNING IN STATISTICS

- CHAPTER 14: SIMULATION OPTIMIZATION

- CHAPTER 15: LEARNING IN MATHEMATICAL PROGRAMMING

- CHAPTER 16: OPTIMIZING OVER CONTINUOUS MEASUREMENTS

- CHAPTER 17: LEARNING WITH A PHYSICAL STATE

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- WILEY SERIES IN PROBABILITY AND STATISTICS

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app