![]()

1

Introduction

Although many gases are natural (air, for example), the term “natural gas” refers to the hydrocarbon-rich gas that is found in underground formations. These gases are organic in origin, and thus along with oil, coal, and peat are called “fossil fuels.” Time and the effects of pressure and temperature have converted the originally living matter into hydrocarbon gases that we call natural gas.

Natural gas is largely made up of methane but also contains other light hydrocarbons, typically ethane through hexane. In addition, natural gas contains inorganic contaminants – notably hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide, but also nitrogen and trace amounts of helium and hydrogen.

The formations and the gas contained therein are almost always associated with water, and thus the gas is usually water-saturated. The water concentration depends on the temperature and pressure of the reservoir and to some extent on the composition of the gas.

Natural gas that contains hydrogen sulfide is referred to as “sour.” Gas that does not contain hydrogen sulfide, or at least contains hydrogen sulfide but in very small amounts, is called “sweet.”

Contaminants in natural gas, like hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide, are usually removed from the gas in order to produce a sales gas. Hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide are called “acid gases” because when dissolved in water they form weak acids.

Hydrogen sulfide must be removed because of its high toxicity and strong, offensive odor. Carbon dioxide is removed because it has no heating value. Another reason these gases must be removed is because they are corrosive. In Alberta, sales gas must typically contain less than 16 ppm1 hydrogen sulfide and less than 2% carbon dioxide. However, different jurisdictions have different standards.

Once removed from the raw gas, the question arises as to what should be done with the acid gas. If there is a large amount of acid gas, it may be economical to build a Claus-type sulfur plant to convert the hydrogen sulfide into the more benign elemental sulfur. Once the H2S has been converted to sulfur, the leftover carbon dioxide is emitted to the atmosphere. Claus plants can be quite efficient, but even so, they also emit significant amounts of sulfur compounds. For example, a Claus plant processing 10 MMSCFD of H2S and converting 99.9% of the H2S into elemental sulfur (which is only possible with the addition of a tail gas clean up unit) emits the equivalent of 0.01 MMSCFD or approximately 0.4 ton/day of sulfur into the atmosphere. Note that there is more discussion of standard volumes and sulfur equivalents later in this chapter.

For small acid gas streams, Claus-type sulfur plants are not feasible. In the past, it was permissible to flare small amounts of acid gas. However, with growing environmental concerns, such practices are being legislated out of existence.

In the natural gas business, acid gas injection has quickly become the method of choice for the disposal of such gases. Larger producers are also considering injection because of the volatility of the sulfur markets.

1.1 Acid Gas

As noted earlier, hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide are called acid gases. When dissolved in water they react to form weak acids.

The formation of acid in water is another reason that acid gases are often removed from natural gas. The acidic solutions are very corrosive and require special materials to handle them.

On the other hand, the acidity of the acid gases is used to our advantage in processes for their removal.

1.1.1 Hydrogen Sulfide

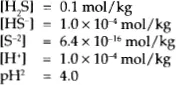

Hydrogen sulfide is a weak, diprotic acid (i.e., it undergoes two acid reactions). The ionization reactions are as follows:

The subscript (aq) indicates that the reaction takes place in the aqueous (water-rich) phase.

It is the H+ ion that makes the solution acidic. Hydrogen sulfide is diprotic because it has two reactions that both form the hydrogen ion. Furthermore, when hydrogen sulfide is dissolved in water it exists as three species – the molecular form (H2S) and the two ionic forms: the bisulfide ion (HS−) and the sulfide ion (S2−).

The measure of how far these reactions proceed is the equilibrium ratios. For our purposes, these ratios are as follows:

where the square brackets indicate the concentration of each species. These relations are valid only if the concentration is small. The fact that these ratios are so small indicates that these reactions do not proceed very far, and thus, in an otherwise neutral solution, most of the hydrogen sulfide is found in the solution in the molecular form. The concentration of the ionic species is greatly affected by the presence of an alkaline and to some extend the presence of an acid. And since hydrogen sulfide is an acid, the effect of an alkaline is very significant.

At 25°C and 101.325 kPa (1 atm) the distribution of the various species in the aqueous solution can be calculated from the solubility and the equilibrium ratios. The distribution is:

The units of concentration used here are molality or moles of species per kg of solvent (water).

1.1.2 Carbon Dioxide

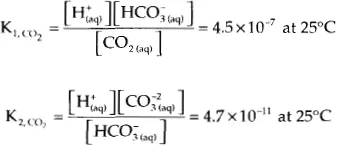

Carbon dioxide is also a weak diprotic acid, but the reactions for CO2 are slightly different. The first reaction is a hydrolysis (a reaction with water):

The second is a simple acid formation reaction:

Again, these reactions take place in the aqueous phase. The carbon dioxide exists in three species in the aqueous phase – the molecular form CO2, and two ionic forms: the bicarbonate ion, also call the hydrogen carbonate ion (HCO3−), and the carbonate ion (CO32−).

The equilibrium ratios for these reactions are:

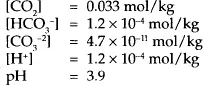

Again, the square brackets are used to indicate the concentration of the various species. As with hydrogen sulfide, these ratios are very small, and thus in an otherwise neutral solution most of the carbon dioxide exist in the molecular form. At 25°C and 101.325 kPa (1 atm) the distribution of the various species in the aqueous solution is:

The pH of the CO2 solution is slightly less than that for H2S even though the solubility of CO2 is significantly less. This is because more of the carbon dioxide ionizes, which in turn produces more of the H+ ion – the acid ion.

1.2 Anthropogenic CO2

The disposal of man-made carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is becoming an undesirable practice. Whether or not one believes that CO2 is harmful to the environment has almost become a moot point. The general consensus is that CO2 is contributing to global climate change. Furthermore, it is clear that legislators all around the world believe that it is a problem. In some countries there is a carbon tax applied to such d...