eBook - ePub

Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

About this book

Lecture Notes: Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics provides all the necessary information, within one short volume, to achieve a thorough understanding of how drugs work, their interaction with the body in health and disease, and how to use these drugs appropriately in clinical situations.

Presented in an easy-to-use format, this eighth edition builds on the clinical relevance for which the title has become well-known, and features an up-to-date review of drug use across all major clinical disciplines, together with an overview of contemporary medicines regulation and drug development.

Key features include:

- A section devoted to the practical aspects of prescribing

- Clinical scenarios and accompanying questions to contextualise information

- End-of-chapter summary boxes

- Numerous figures and tables which help distil the information for revision purposes

Whether you need to develop or refresh your knowledge of pharmacology, Lecture Notes: Clinical Pharmacology and Therpeutics presents 'need to know' information for those involved in prescribing drugs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics by John L. Reid,Matthew R. Walters,Gerard A. McKay,Gerard A. McKay,Matthew R. Walters in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Principles of Clinical Pharmacology

Chapter 1

Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

Clinical scenario

A 50-year-old obese man with type-2 diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia has made arrangements to see his general practitioner to review his medications. He is on three different drugs for his diabetes, four different antihypertensives, a statin for his cholesterol and a dispersible aspirin. These medications have been added over a period of 2 years despite him not having any symptoms and he feels that if anything they are giving him symptoms of fatigue and muscle ache. He has also read recently that aspirin may actually be bad for patients with diabetes. He is keen to know why he is on so many medications, if the way he is feeling is due to the medications and whether they are interfering with the action of each other. What knowledge might help the general practitioner deal with this?

Key points – what is pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics?

The variability in the relationship between dose and response is a measure of the sensitivity of a patient to a drug.

This has two components: dose – concentration and concentration – effect.

The latter is termed pharmacodynamics. The description of a drug concentration profile against time is termed pharmacokinetics.

In simple terms pharmacodynamics is what the drug does to the individual taking it and pharmacokinetics is what the individual does to the drug.

Clinical pharmacology seeks to explore the factors that underlie variability in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics for the optimisation of drug therapy in individual patients.

Introduction

A basic knowledge of the mechanism of action of drugs and how the body deals with drugs allows the clinician to prescribe them safely and effectively. Prior to the twentieth century, prescribing medication was based on intelligent observation and folklore with medical practices depending largely on the administration of mixtures of natural plant or animal substances. These preparations contained a number of pharmacologically active agents in variable amounts (e.g. powdered bark from the cinchona tree, now known to contain quinine, being used by natives of Peru to treat ‘fevers’ caused by malaria).

During the last 100 years an increased understanding has developed for biochemical and pathophysiological factors that influence disease. The chemical synthesis of agents with wellcharacterised and specific actions on cellular mechanisms has led to the introduction of many powerful and effective drugs. Additionally, advances in the detection of these compounds in body fluids have facilitated investigation into the relationships between the dosage regimen, the profile of drug concentration against time in body fluids, notably the plasma, and corresponding profiles of clinical effect. Knowledge of this concentration-effect relationship, and the factors that influence drug concentrations, underpin early stages of the drug development process.

More recently the development of genomics and proteomics has provided additional insights and opportunities for drug development with new and more specific targets. Such knowledge will replace the concept of one drug and/or one dose fitting all.

Principles of drug action (pharmacodynamics)

Pharmacological agents are used in therapeutics to:

1 Alleviate symptoms, for example:

- paracetamol for pain

- glyceryl trinitrate spray for angina

2 Improve prognosis – this can be measured in number of different ways – usually measured as a reduction in morbidity or mortality, for example:

- prevent or delay end-stage consequences of disease, e.g. anti-hypertensive medication and statins in cardiovascular disease, levodopa in Parkinson’s disease

- replace deficiencies, e.g. levothyroxine in hypothyroid

- cure disease, e.g. antibiotics, chemotherapy

Some drugs will both alleviate symptoms and improve prognosis, e.g. beta-blockers in ischaemic heart disease. If a prescribed drug is doing neither, one must question the need for its use and stop it. Even if there is a clear indication for use, the potential for side effects and interactions with any other drugs the patient is on also needs to be taken into account.

Mechanism of drug action

Action on a receptor

A receptor is a specific macromolecule, usually a protein, situated either in cell membranes or within the cell, to which a specific group of ligands, drugs or naturally occurring substances (such as neurotransmitters or hormones), can bind and produce pharmacological effects. There are three types of ligands: agonists, antagonists and partial agonists.

An agonist is a substance that stimulates or activates the receptor to produce an effect, e.g. salbutamol at the β2-receptor.

An antagonist prevents the action of an agonist but does not have any effect itself, e.g. losartan at the angiotensin II receptor.

A partial agonist stimulates the receptor to a limited extent, while preventing any further stimulation by naturally occurring agonists, e.g. aripiprazole at the D2 and 5-HT1A receptors.

The biochemical events that result from an agonist–receptor interaction to produce an effect are complex. There are many types of receptors and in several cases subtypes have been identified which are also of therapeutic importance, e.g. α and β adrenoceptors, nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors.

Action on an enzyme

Enzymes, like receptors, are protein macromolecules with which substrates interact to produce activation or inhibition. Drugs in common clinical use, which exert their effect through enzyme action generally do so by inhibition, for example:

1 aspirin inhibits platelet cyclo-oxygenase

2 ramipril inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme

Drug receptor antagonists and enzyme inhibitors can act as competitive, reversible antagonists or as non-competitive, irreversible antagonists. Effects of competitive antagonists can be overcome by increasing the dose of endogenous or exogenous agonists, while effects of irreversible antagonists cannot usually be overcome resulting in a longer duration of the effect.

Action on membrane ionic channels

The conduction of impulses in nerve tissues and electromechanical coupling in muscle depend on the movement of ions, particularly sodium, calcium and potassium, through membrane channels. Several groups of drugs interfere with these processes, for example:

1 nifedipine inhibits the transport of calcium through the slow channels of active cell membranes

2 furosemide inhibits Na/K/Cl co-transport in the ascending limb of the loop of Henle

Cytotoxic actions

Drugs used in cancer or in the treatment of infections may kill malignant cells or micro-organisms. Often the mechanisms have been defined in terms of effects on specific receptors or enzymes. In other cases chemical action (alkylation) damages DNA or other macromolecules and results in cell death or failure of cell division.

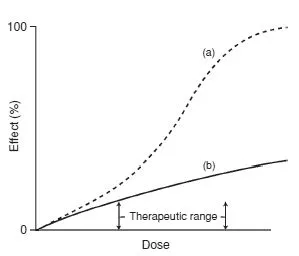

Dose–response relationship

Dose–response relationships may be steep or flat. A steep relationship implies that small changes in dose will produce large changes in clinical response or adverse effects, while flat relationships imply that increasing the dose will offer little clinical advantage (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Schematic examples of a drug (a) with a steep dose– (or concentration–) response relationship in the therapeutic range, e.g. warfarin an oral anticoagulant; and (b) a flat dose– (or concentration–) response relationship within the therapeutic range, e.g. thiazide diuretics in hypertension.

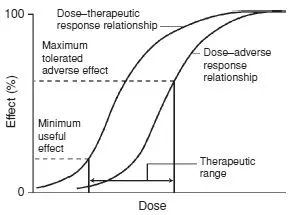

Figure 1.2 Schematic diagram of the dose–response relationship for the desired effect (dose–therapeutic response) and for an undesired adverse effect. The therapeutic index is the extent of displacement of the two curves within the normal dose range.

In clinical practice the maximum therapeutic effect may often be unobtainable because of the appearance of adverse or unwanted effects: few, if any, drugs cause a single pharmacological effect.

The concentration–adverse response relationship is often different in shape and position to that of the concentration–therapeutic response relationship. The difference between the concentration that produces the desired effect and the concentration that causes adverse effects is called the therapeutic index and is a measure of the selectivity of a drug (Fig. 1.2).

The shape and position of dose–response curves for a group of patients is variable because of genetic, environmental and disease factors. However, this variability is not solely an expression of differences in response to drugs. It has two important components: the dose–plasma concentration relationship and the plasma concentration–effect relationship.

Dose → Concentration → Effect

With the development of specific and sensitive chemical assays for drugs in body fluids, it has been possible to characterise dose–plasma concentration relationships so that this component of the variability in response can be taken into account when drugs are prescribed for patients with various disease states. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index it may be necessary to measure plasma concentrations to assess the relationship between dose and concentration in individual patients (see Chapter 21, section ‘Therapeutic drug monitoring’).

Principles of pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Drug absorption after oral administration has two major components: absorption rate and bioavailability. Absorption rate is controlled partially by the physicochemical characteristics of the drug but in many cases it is modified by the formulation. A reduction in absorption rate can lead to a smoother concentration–time profile with a lower potential for concentration-dependent adverse effects and may allow less frequent dosing.

Bioavailability is the term used to describe the fraction of the dose that is absorbed into the systemic circulation. It can range from 0 to 100% and depends on a number of physicochemical and clinical factors. Low bioavailability may occur if the drug has low solubility or is destroyed by the acid in the stomach. Changing the formulation can affect the bioavailability of a drug and it can also be altered by food or the co-administration of other drugs. For example, antacids can reduce the absorption of quinolone antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin, by binding them in the gut. Other factors influencing bioavailability include metabolism by gut flora, the intestinal wall or the liver.

First-pass metabolism refers to metabolism of a drug that occurs en route from the gut lumen to the systemic circulation. For the majority of drugs given orally, absorption occurs across the portion of gastrointestinal epithelium that is drained by veins forming part of the hepatoportal system. Consequently, even if they are well absorbed, drugs must pass through the liver before reaching the systemic circulation. For drugs that are susceptible to extensive hepatic metabolism, a substantial proportion of an orally administered dose can be metabolised before it ever reaches its site of pharmacological action, e.g. insulin metabolism in the gut lumen is so extensive that it renders oral therapy impossible.

The importance of first-pass metabolism is twofold:

1 It is one of the reasons for apparent differences in drug bioavailability between individuals. Even healthy people show considerable variation in liver metabolising capacity.

2 In patients with severe liver disease first-pass metabolism may be dramatically reduced, leading to the appearance of greater amounts of active drug in the systemic circulation.

Distribution

Once a drug has gained access to the bloodstream it begins to distribute to the tissues. The extent of this distribution depends on a number of factors including plasma protein binding, lipid solubility and regional blood flow. The volume of distribution, VD, is the apparent volume of fluid into which a drug distributes on the basis of the amount of drug in the body and the measured concentration in the plasma or serum. If a drug was wholly confined to the plasma, VD would equal the plasma volume – approximately 3 L in an adult. If, on the contrary, the drug was distributed throughout the body water, VD would be approximately 42 L. In reality, drugs are rarely distributed into physiologically relevant volumes. If most of the drug is bound to tissues, the plasma concentration will be low and the apparent VD will be high, while high plasma protein binding will tend to maintain high concentrations in the blood and a low VD will result. For the majority of drugs, VD depends on the balance between plasma binding and sequestration or binding by various body tissues, for example, muscle and fat. Volume of distribution can therefore vary considerably.

Clinical relevance of volume of distribution

Knowledge of volume of distribution (VD) can be used to determine the size of a loading dose if an immediate response to treatment is required. This assumes that therapeutic success is closely related to the plasma concentration and that there are no adverse effects if a relatively large dose is suddenly administered. It is sometimes employed when drug response would take many hours or days to develop if the regular maintenance dose was given from the outset, e.g. digoxin.

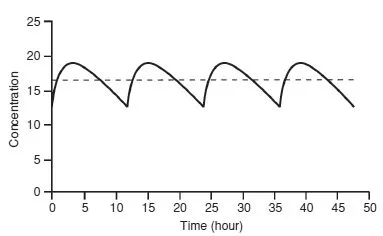

Figure 1.3 Steady-state concentration–time profile for an oral dose (—) and 0 a constant rate intravenous infusion 0 5 (− − − – -).

In practice, weight is the main determinant to calculating the dose of a drug where there is a narrow therapeutic index.

Plasma protein binding

In the blood, a proportion of a drug is bound to plasma proteins – mainly albumin (acidic drugs) and α1-acid glycoprotein (basic drugs). Only the unbound, or free, fraction distributes because the protein-bound complex is too large to pass through membranes. It is the unbound portion that is generally responsible for clinical effects – both the target response and the unwanted adverse effects. Changes in protein binding (e.g. resulting from displacement interactions) generally lead to a transient increase in free concentration but are rarely clinically relevant. However, a lower total concentration will be present and the measurement might be misinterpreted if the higher free fraction is not taken into account. This is a common problem with the interpretation of phenytoin concentrations, where free fraction can range from 10% in a normal patient to 40% in a patient with hypoalbuminaemia and renal impairment.

Clearance

Clearance is the sum of all drug-eliminating processes, principally determined by hepatic metabolism and renal excretion. It can be defined as the theoretical volume of fluid from which a drug is completely removed in a given period of time.

When a drug is administered continuously by intravenous infusion or repetitively by mouth, a balance is eventually achieved between its input (dosing rate) and its output (the amount eliminated over a given period of time). This balance gives rise to a constant amount of drug in the body which depends on the dosing rate and clearance. This amount is reflected in the plasma or serum as a steady-state concentration (Css). A constant rate intravenous infusion will yield a constant Css, while a drug administered orally at regular intervals will result in fluctuation between peak and trough concentrations (Fig. 1.3).

Clearance depends critically on the efficiency with which the liver and/or kidneys can eliminate a drug; it will vary in disease states that affect these organs, or that affect the blood flow to these organs. In stable clinical conditions, clearance remains constant and is directly proportional to dose rate. The important implication is that if the dose rate is doubled, the Cssaverage doubles: if the dose rate is halved, the Cssaverage is halved for most drugs. In pharmacokinetic terms this is referred to as a first-order or linear process, and results from the fact that the rate of elimination is proportional to the amount of drug present in the body.

Single intravenous bolus dose

A number of other important pharmacokinetic principles can be appreciated by considering the concentrations that result following a single intravenous bolus dose (see Fig. 1.4) and through a number of complex equations the time at which steady state will be achieved after starting a regular treatment schedule or after any change in dose can be predicted.

As a rule, in the absence of a loading dose, steady state is attained after four to five half-lives (Fig. 1.5).

Furthermore, when toxic drug levels have been inadvertently produced, it is very useful to estimate how long it will take for such levels to reach the therapeutic range, or how long it will take for the entire drug to be eliminated once the drug has been stopped. Usually, elimination is effectively complete after four to five half-lives (Fig. 1.6).

The elimination half-life can also be used to determine dosage intervals to achieve a target concentration–time profile. For example, in order to obtain a gentamicin peak of 8 mg/L and a trough of 0.5 mg/L in a patient with an elimination halflife of 3 hours, the dosage interval should be 12 hours. (The concentration will fall from 8–4 mg/L in 3 hours to 2 mg/L in 6 hours, to 1 mg/L in 9 hours and to 0.5 mg/L in 12 hours.) However, for many drugs, dosage regimens should be designed to maintain concentrations within a range that avoids high (potentially toxic) peaks or low, ineffective troughs. Excessive fluctuations in the concentration-time profile can be prevented by giving the drug at intervals of less than one halflife or by using a slow-release formulation.

Figure 1.4 Plot of concentration versus time after a bolus intravenous injection. The intercept on the y- (concentration) axis, C0,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Principles of Clinical Pharmacology

- Part 2: Aspects of Therapeutics

- Part 3: Practical Aspects of Prescribing

- Index