eBook - ePub

Trace Quantitative Analysis by Mass Spectrometry

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Trace Quantitative Analysis by Mass Spectrometry

About this book

This book provides a serious introduction to the subject of mass spectrometry, providing the reader with the tools and information to be well prepared to perform such demanding work in a real-life laboratory. This essential tool bridges several subjects and many disciplines including pharmaceutical, environmental and biomedical analysis that are utilizing mass spectrometry:

- Covers all aspects of the use of mass spectrometry for quantitation purposes

- Written in textbook style to facilitate understanding of this topic

- Presents fundamentals and real-world examples in a 'learning-though-doing' style

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Measurement, Dimensions and Units

Standards of Comparison

The US standard railroad gauge (distance between the rails) is 4 feet, 8.5 inches. That’s a very strange number, why was it used? Because the first railroads were built in Britain, and the North American railroads were built by British immigrants.

Why did they build them like that? Because the first railways (lines and rolling stock) were built by the same companies that built the pre-railroad tramways, and they used the same old gauge. All right, why did ‘they’ use that gauge? Because the tramways used the same jigs and tools that had been used for building wagons, and the wagons used that wheel spacing.

Are we getting anywhere? Why did the wagons use that strange wheel spacing? Well, if they tried to use any other spacing the wagons would break down on some of the old long distance roads, because that’s the spacing of the old wheel ruts.

So who built these old rutted roads? The first long distance roads in Europe were built by Imperial Rome for the purposes of the Roman Legions. These roads were still widely used in the 19th century. And the ruts? The initial ruts, which everyone else had to match in case they destroyed their wagons, were made by Roman war chariots. Since the chariots were made for Imperial Rome they were all alike, including the wheel spacing. So now we have an answer to the original question. The US standard railroad gauge of 4 feet, 8.5 inches is derived from the original specification for an Imperial Roman army war chariot.

The next time you are struggling with conversion factors between units and wonder how we ended up with all this nonsense, you may be closer to the truth than you knew. Because the Imperial Roman chariots were made to be just wide enough to accommodate the south ends of two war horses heading north.

And this is not yet the end! The US space shuttle has two big booster rockets attached to the sides of the main fuel tank. These are solid rocket boosters (SRBs) made in a factory in Utah. It has been alleged that the engineers who designed the SRBs would have preferred to make them a bit fatter, but the SRBs had to be shipped by train from the factory to the launch site. The railroad line from the factory happens to run through a tunnel in the mountains, and the SRBs had to fit through that tunnel. The tunnel is only slightly wider than the railroad track, and we now know the story behind the width of the track!

So, limitations on the size of crucial components of the space shuttle arose from the average width of the Roman horses’ rear ends.

1.1 Introduction

All quantitative measurements are really comparisons between an unknown quantity (such as the height of a person) and a measuring instrument of some kind (e.g., a measuring tape). But to be able to communicate the results of our measurements among one another we have to agree on exactly what we are comparing our measurements to. If I say that I measured my height and the reading on the tape was 72, that does not tell you much. But if I say the value was 72 inches, that does provide some meaningful information provided that you know what an inch is (tradition tells us that the inch was originally defined as the length of part of the thumb of some long-forgotten potentate but that does not help us much). But even that information is incomplete as we do not know the uncertainty in the measurement. Most people understand in a general way the concepts of accuracy (deviation of the measured value from the ‘true’ value) and precision (a measure of how close is the agreement among repeated measurements of the same quantity) as different aspects of total uncertainty, and such a general understanding will suffice for the first few chapters of this book. However, the result of a measurement without an accompanying estimate of its uncertainty is of little value, and a more complete discussion of experimental uncertainty is provided in Chapter 8 in preparation for the practical discussions of Chapters 9 and 10.

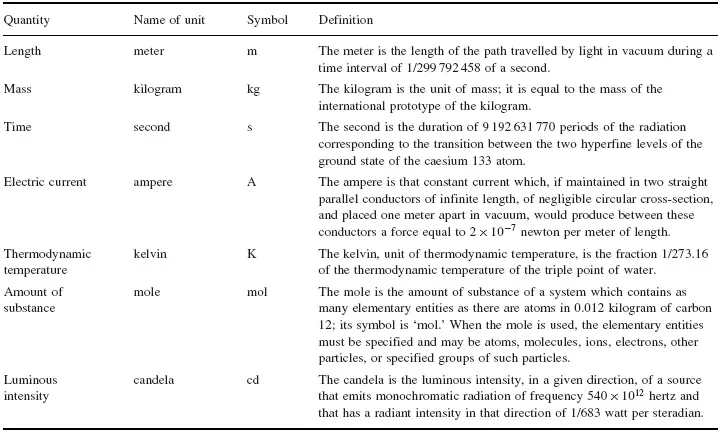

Actually, the only correct answer to the question ‘what is an inch’ is that one inch is defined as exactly 2.54 centimeters (zero uncertainty in this defined conversion factor). So now we have to ask what is a centimeter, and most of us know that a centimeter is 1/100 of a meter. So what is a meter? This is starting to sound about as arbitrary as the Roman horses’ hind quarters mentioned in the text box but in this case we can give a more useful if less entertaining answer: The meter is the length of the path traveled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299 792 458 of a second. Note that the effect of this definition is to fix the speed of light in vacuum at exactly 299 792 458 meters per second, and that we still have not arrived at a final definition of the meter until we have defined the second (Table 1.1). This is the internationally accepted definition of the meter, established in 1983, and forms part of the International System of Units (Système Internationale d’Unites, known as SI for short). The SI establishes the standards of comparison used by all countries when the measured values of physical and chemical properties are reported. Such an international agreement is essential not only for science and technology, but also for trade. For example, consider the potential confusion arising from the following example:

1 US quart (dry) = 1.10122 litres

1 US quart (liquid) = 0.94635 litres

1 Imperial (UK/Canada) quart (liquid)=1.136523 litres

Table 1.1 SI Base Quantities and Units

(The litre is defined in the SI as 1/1000 of a cubic meter: 1L = 10-3 m3). Many other examples of such ambiguities can be given (see, for example, the unit conversions at: http://www.megaconverter.com/Mega2/index.xhtml). Such discrepancies may not seem to be very important when only a single quart is considered, but in international trade where literally millions of quarts of some commodity might be traded, the 19% difference between the two definitions of the liquid quart could lead to extreme difficulties if the ambiguity were not recognized and taken into account. In a lecture on ‘Money as the measure of value and medium of exchange’, delivered in 1763 at the University of Glasgow, Adam Smith commented (Smith 1763, quoted in Ashworth 2004):

‘Natural measures of quantity, such as fathoms, cubits, inches, taken from the proportion of the human body, were once in use with every nation. But by a little observation they found that one man’s arm was longer or shorter than another’s, and that one was not to be compared with the other; and therefore wise men who attended to these things would endeavour to fix upon some more accurate measure, that equal quantities might be of equal values. Their method became absolutely necessary when people came to deal in many commodities, and in great quantities of them.’

It is precisely this kind of uncertainty that the SI is designed to avoid in both science and in trade and commerce. In this regard it is unfortunate to note that even definitions of words used to denote numbers are still subject to ambiguity. For example, in most countries ‘one billion’ (or the equivalent word in a country’s official language) is defined as 1012 (a million million), but in the USA (and increasingly in other English-speaking countries) a billion is used to represent 109 (a thousand million) and 1012 is referred to as a ‘trillion’. In view of this ambiguity it is always preferable to use scientific numerical notation.

1.2 The International System of Units (SI)

An excellent source of information about the SI can be found at the website of the US National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST): http://physics.nist.gov/cuu/Units/index.xhtml

Here we shall be mainly concerned with those quantities that directly affect quantitative measurements of amounts of chemical substances by mass spectrometry. However, it is appropriate to briefly describe some general features of the SI.

Early History of the SI

There is a strong French connection with the SI, including its name and the location in Paris of the central organization that coordinates this international agreement (Bureau International des Poids et Mesures, or BIPM), and the international guiding body CIPM (Comité International de Poids et Mesures, i.e., International Committee for Weights and Measures). This connection was established at the time of the French Revolution when the revolutionary government decided that the chaotic state of weights and measures in France had to be fixed. The intellectual leader in this initiative, that resulted in the so-called Metric System, was the chemist Antoine Lavoisier, famous for his demonstration that combustion involves reaction with oxygen and that water is formed by combustion of two parts of hydrogen with one of oxygen. His efforts resulted in the creation of two artifacts made of platinum (chosen because of its resistance to oxidation), one representing the meter as the new unit of length between two scratch marks on the platinum bar, and the other the kilogram. These artifacts were housed in the Archives de la République in Paris in 1799, and this represents the first step taken towards establishment of the modern SI.

Sadly, Lavoisier did not live to see this realization of his ideas. Despite his fame, and his services to science and his country (he was a liberal by the standards of pre-revolutionary France and played an active role in the events leading to the Revolution and, in its early years, formulated plans for many reforms), he fell into disfavour because of his history as a former farmer-general of taxes, and was guillotined in 1794. After his arrest and a trial that lasted less than a day, Lavoisier requested postponement of his execution so that he could complete some experiments, but the presiding judge infamously refused: ‘L’état n’a pas besoin de savants’ (the state has no need of intellectuals).

Any system of measurement must decide what to do about the fact that there are literally thousands of physical properties that we measure, each of which is expressed as a measured number of some well-defined unit of measurement. It would be impossible to set up primary standards for the units of each and every one of these thousands of physical quantities, but fortunately there is no need to do so since there are many relationships connecting the measurable quantities to one another. A simple example that is of direct importance to the subject of this book is that of volume; as mentioned above, the SI unit of volume (cubic meter) is simply related to the SI unit for length via the physical relationship between the two quantities. So the first question to be settled concerns how many, and which, physical quantities should be defined as SI base quantities (sometimes referred to as dimensions), for which the defined units of measurement can be combined appropriately to give the SI units for all other measurable quantities.

At one time it was thought to be more ‘elegant’ to work with a minimum possible number of dimensions and their defined units of measurement, and this pseudo-esthetic criterion gave rise to the three-dimensional centimeter-gram-second (cgs) and meter-kilogram-second (MKS) systems. However, it soon became apparent that utility and convenience were more important than perceived elegance! As a simple example, consider Coulomb’s Law for the electrostatic force F between two electric charges q1 and q2 separated by a distance r in a vacuum:

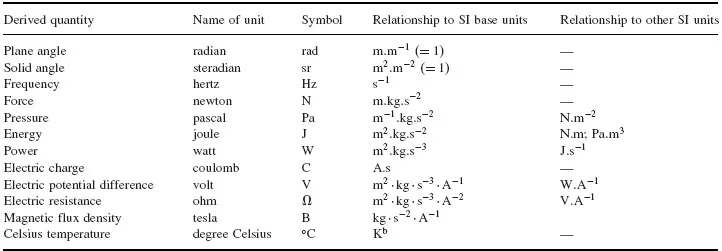

In the simple form of Coulomb’s Law as used with the cgs system, the Coulomb’s Law Constant ko is treated as a dimensionless constant with value 1. (This is not the case in the SI, where k = 1/(4πεo) where εo is the permittivity of free space =8.854187817 × 10–12 s4A2kg–1m–3). By Newton’s Second Law of Motion, force is given as (mass × acceleration), i.e., (mass × length × time–2), so in the cgs system q1 .q2 corresponds to (mass × length3 × time–2); thus, in such a three-dimensional measurement system, electrical charge q corresponds to (mass ½ × length3/2 × time–1). This very awkward (and inelegant!) result involving fractional exponents becomes even more cumbersome when magnetism is considered. Once it was accepted that usefulness was the only criterion for deciding on the base physical quantities (dimensions) and their units of measurement, it was finally agreed that the most useful number of dimensions for the SI was seven. Some of these seven are of little or no direct consequence for this book, but for the sake of completeness they are all listed in Table 1.1. Some important SI units, that are derived from the base units but have special names and symbols, are listed in Table 1.2.

The two base quantities (and their associated SI units) that are most important for quantitative chemical analysis are amount of substance (mole) and mass (kilogram), although length (meter) is also important via its derived quantity volume in view of the convenience introduced by our common use of volume concentrations for liquid solutions. (Note, however, that the latter will in principle vary with temperature as a result of expansion or contraction of the liquid).

The kilogram is unique among the SI base units for two reasons. Firstly, the unit of mass is the only one whose name contains a prefix (this is a historical accident arising from the old centimeter-gram-second system of measurement mentioned above). Names and symbols for decimal multiples and submultiples of the unit of mass are formed by attaching prefix names to the unit name ‘gram’ and prefix symbols to the unit symbol ‘g’, not to the ‘kilogram’. (A list of SI prefixes denoting powers of 10 is given in Table 1.3). The other unique aspect of the kilogram is that it is currently (2007) the only SI base unit that is defined by a physical artifact, the so-called international prototype of the kilogram (made of a platinum–iridium alloy and maintained under carefully controlled conditions at the BIPM in Paris (Figure 1.1)). This international prototype is used to calibrate the national kilogram standards for the countries that subscribe to the SI.

Table 1.2 Some SI Derived units with special names and symbolsa

a for a complete list and discussion, see Taylor (1995) and Taylor (2001).

b the size of the two units is the same, but Celsius temperature (°C) = thermodynamic temperature (K) – 2...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- copyright

- Dedication

- Content

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Measurement, Dimensions and Units

- 2: Tools of the Trade I. The Classical Tools

- 3: Tools of the Trade II. Theory of Chromatography

- 4: Tools of the Trade III. Separation Practicalities

- 5: Tools of the Trade IV. Interfaces and Ion Sources for Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

- 6: Tools of the Trade V. Mass Analyzers for Quantitation: Separation of Ions by m/z Values

- 7: Tools of the Trade VI. Ion Detection and Data Processing

- 8: Tools of the Trade VII: Statistics of Calibration, Measurement and Sampling

- 9: Method Development and Fitness for Purpose

- 10: Method Validation and Sample Analysis in a Controlled Laboratory Environment

- 11: Examples from the Literature

- Epilog

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Trace Quantitative Analysis by Mass Spectrometry by Robert K. Boyd,Cecilia Basic,Robert A. Bethem in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Spectroscopy & Spectrum Analysis. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.