![]()

Part I

Binding Thermodynamics

![]()

Chapter 1

Statistical Thermodynamics of Binding and Molecular Recognition Models

Kim A. Sharp

1.1 Introductory Remarks

Equilibrium binding or association of two molecules to form a bimolecular complex, A + B

AB, is a thermodynamic event. This chapter will cover some of the fundamental thermodynamics and statistical mechanics aspects of this event. The aim is to introduce general principles and broad theoretical approaches to the calculation of binding constants, while later chapters will provide examples. Only the noncovalent, bimolecular association under ambient pressure conditions will be considered. However, extension to higher order association involves no additional principles, and extension to high pressure by inclusion of the appropriate pressure–volume work term is straightforward. In terms of the binding reaction above, the association and dissociation constants are defined as

K = [AB]/[A][B] and

KD = [A][B]/[AB] respectively, where [] indicates concentration. Either

K or

KD is the primary experimental observable measured in binding reactions.

KD is sometimes obtained indirectly by inhibition of binding of a different ligand as a

Ki. From a thermodynamic perspective, the information content from

K,

KD, and

Ki is the same.

1.2 The Binding Constant and Free Energy

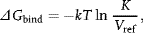

To connect the experimental observable K to thermodynamics, one often finds in the literature the relationship

where k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, and ΔGbind is the “absolute” or “standard” binding free energy. Several comments are given to avoid misuse of this expression. First, one cannot properly take the logarithm of a quantity with units such as K, so Eq. (1.1) is implicitly

where Vref is the reference volume in units consistent with the units of concentration in K, that is, 1 l/mol or about 1660 Å3/molecule for molarity units. The choice of Vref is often referred to as the “standard state” problem. Equivalently, one says that ΔGbind is the free energy change when reactants A and B and the product AB are all at the reference concentration. Second, although the units of concentration used in K are almost always moles/liter, this is entirely a convention, so the actual numerical value for ΔGbind obtained from Eq. (1.2) is arbitrary. Put another way, any method for calculating the free energy of binding must explicitly account for a particular choice of Vref before it can meaningfully be compared with experimental values of ΔGbind obtained using Eq. (1.2). Furthermore, ligand efficiency-type measures, such as ΔGbind/n where n is the number of heavy atoms in a ligand or the molecular weight of a ligand [1], can change radically with (arbitrary) choice of concentration units. Of course, differences in ΔGbind can be sensibly compared provided the same reference state concentration is used. Finally, in Eq. (1.2), the free energy actually depends on the ratio of activities of reactants and products, not on concentrations. For neutral ligands and molecules of low charge density at less than micromolar concentrations, the activity and concentration are nearly equal and little error is introduced. However, this is not true for high charge density molecules such as nucleic acids and many of the ligands and proteins that bind to nucleic acids. Here, the activity coefficient can be substantially different from unity even at infinitely low concentration. Indeed, much of the salt dependence of ligand–DNA binding can be treated as an activity coefficient effect [2–4]. The issue of standard state concentrations, the formal relationship between the binding constant and the free energy, and the effect of activity coefficients are all treatable by a consistent statistical mechanical treatment of binding, as described in Section 1.3.

1.3 A Statistical Mechanical Treatment of Binding

Derivation of a general expression for the binding constant follows closely the approach of Luo and Sharp [5], although somewhat different treatments using chemical potentials, which provide the same final result, are given elsewhere [6–8]. It is a statistical mechanical principle that any equilibrium observable can be obtained as an ensemble, or Boltzmann weighted average, of the appropriate quantity. Here, the binding constant K = [AB]/[A][B] is the required observable. Consider a single molecule each of A and B in some volume V (Figure 1.1) and for convenience define a coordinate system centered on B (the target) in a fixed orientation. Over time, the ligand (A) will explore different positions and orientations (poses) relative to B, where r and Ω represent the three position and three orientation coordinates of A with respect to B. Now A and B interact with each other with an energy that depends not only on their relative position (r, Ω) but in general also on the conformations of A, B, and the surrounding solvent. If na, nb, ns are the number of atoms in A, B, and solvent, then the energy is a function of 3na + 3nb + 3ns − 6 coordinates. In principle, one could keep all these degrees of freedom explicit. From a practical standpoint, this would be a complicated and expensive function to evaluate. However, one may integrate over the solvent coordinates and the (3na − 6) +(3nb − 6) internal coordinates so that the interaction between A and B for a given (r, Ω) is described by an interaction potential of mean force (pmf) ω(r, Ω). If one defines the pmf between A and B at infinite separation in their equilibrium conformations to be 0, then ω(r, Ω) is the thermodynamic work of bringing A and B from far apart to some mutual pose (r, Ω), accounting for both solvent effects and internal degrees of free...