- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ecological Aspects of Nitrogen Metabolism in Plants

About this book

Ecological Aspects of Nitrogen Acquisition covers how plants compete for nitrogen in complex ecological communities and the associations plants recruit with other organisms, ranging from soil microbes to arthropods. The book is divided into four sections, each addressing an important set of relationships of plants with the environment and how this impacts the plant's ability to compete successfully for nitrogen, often the most growth-limiting nutrient. Ecological Aspects of Nitrogen Acquisition provides thorough coverage of this important topic, and is a vitally important resource for plant scientists, agronomists, and ecologists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section 1

The Nitrogen Cycle

The Nitrogen Cycle

Chapter 1

The New Global Nitrogen Cycle

The New Global Nitrogen Cycle

Introduction

Almost 80% of the atmosphere is N2. And nitrogen, in reactive forms is essential for life on earth and is crucial for sustainable development.* Nitrogen in our environment has both benefits as well as negative consequences. The primary benefit of nitrogen is the stimulation of plant growth in agriculture for food, feed, and fuel, whereas the negative aspects include almost all environmental impacts. Compared to elements such as carbon, sulfur, or phosphorus, nitrogen contributes to a variety of negative impacts, most interrelated, such as climate change, eutrophication, soil acidification, degraded human health, loss of biodiversity, etc. In 2008 we celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of the invention of the production of ammonia by Fritz Haber in 1908. Ammonia is the basis for fertilizer production, and Carl Bosch was able to turn that ammonia production into an industrial process (Smil, 2001; Erisman et al., 2008). Bosch and Haber were awarded the Nobel Prize for their achievements. Ammonia is not only the basis for fertilizer, but also for many industrial chemicals, including explosives. So, overall, the Haber-Bosch process was beyond doubt one of the most important inventions of the twentieth century (Erisman et al., 2008). Over the past decades the production of fertilizer has become very energy and economically efficient (Kongshaug, 1998) and on a large scale has increased agricultural productivity. Without fertilizer input, the biosphere would produce 48% less food (Erisman et al., 2008). Therefore, at present, we cannot live without fertilizer. At the same time, industrialization increased the use of fossil fuels. To use the energy from fossil fuels, they are burned, resulting in a large release of oxidized nitrogen (NOx) into the atmosphere. Vehicular traffic, energy use, and industry are the principal sources of oxidized forms of Nr. The dispersion of NOx has affected human health and increased nitrogen deposition in remote areas leading to eutrophication (Erisman and Fowler, 2003).

This book is dedicated to plant “strategies” to acquire, assimilate, and conserve N. Much emphasis is given to plant interactions with microorganisms (Frankia, rhizobia, mycorrhizae). Biological N-fixation is prominently covered and is an important part of the nitrogen cycle. However, in order to establish the need for knowledge in the area of biological N fixation (and the N “conduits” that mycorrhizae provide for delivering soil N to plant), we have to address the “big picture” first, providing background on the major components of the nitrogen cycle on different scales, emphasizing the human contribution to the increased cycling of nitrogen in the biosphere and the resulting impacts on ecosystems and humans. This introductory chapter addresses these issues as a global overview of the human influence on the nitrogen cycle.

The Preindustrial Nitrogen Cycle

Nitrogen is an important element—the most abundant constituent of the atmosphere, hydrosphere, as well as the biosphere. It is also one of the essential elements for the growth of plants and animals and has a crucial role in ecology and in the environment. It is useful to look at the reactions of elements in the form of a closed cycle. Such a cycle is often termed a biogeochemical cycle because chemistry, biology, and geology all provide important inputs. Cycling of elements is often governed by kinetics and may involve the input of energy, so that chemical equilibrium states are not attained. The ultimate source of energy for driving energetically uphill reactions is the sun. The earth’s surface receives an average radiation input of 100–300 W/m2 % day, depending on latitude. Some of this is captured by photosynthesis, and is used to produce high-energy content molecules, such as oxygen. Because of the inherently low efficiency of the photosynthetic process and the production of phytomass, energy supply from this source has low power densities and hence high land demands. Recent estimates of the global terrestrial net primary productivity (NPP) average approximately 120 gigaton (Gton) of dry biomass produced annually, and that contains some 1,800 × 1018 joules (1,800 exajoule [EJ]) of energy (Smil, 2004). In principle, there is globally enough possible annual crop growth to produce the food needed to feed the population currently and for the coming decades. Furthermore, there is enough annual production of new biomass to cover up to four times current human annual energy use. However, in order to grow, collect, and use biomass in a sustainable way to satisfy human food and energy needs, a well-regulated and optimized process is needed.

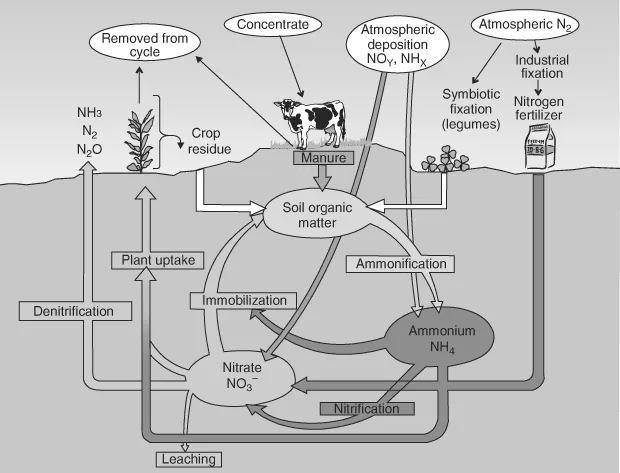

The atmosphere contains mostly elemental di-nitrogen, along with other nitrogen containing trace gases (ammonia, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and nitrous oxide). Aquatic systems primarily contain soluble forms of nitrogen, such as nitrate and ammonia/ammonium, as well as biological nitrogen found in proteins, DNA, RNA, and other compounds that make up living systems. Since lone pairs of electrons on nitrogen are usually basic, ammonia coexists in both the protonated and de-protonated forms near neutral pH. The most important aspect of the environmental nitrogen cycle is the dynamic exchange of chemical species that occurs between the atmosphere and the surface landmasses and oceans. Figure 1.1 illustrates the nitrogen cycle.

Figure 1.1. Illustration of the nitrogen cycle.

From Figure 1.1, it is obvious that living systems are the main players in the interconversions of the reduced and oxidized forms of nitrogen. They play an important role in providing reduced nitrogen compounds for the global cycle, by denitrification processes (the conversion of nitrate to N2 and N2O), biosynthesis (making amino acids, DNA, and RNA), and nitrogen fixation (reduction of N2 to NH2 by both free-living bacteria and bacteria associated with plants, usually in root nodules, the so-called biological nitrogen fixation [BNF]) (Marschner, 1997). Nearly all organisms can use ammonia for biosynthesis (ammonia assimilation). Ammonia is also a major metabolic end product, as in the bacterial decomposition of dead organisms (ammonification). Mammals eliminate ammonia; however, the liver transforms it into the less toxic compound urea before excreting it.

Although reduced nitrogen is preferred for biosynthetic reactions, plants have also learned to capture needed nitrogen by assimilatory nitrate reduction (Marschner, 1997). This evolutionary consequence came about because nitrate is the dominant soluble form of nitrogen in aerated soils. Formation of reduced nitrogen compounds is energetically uphill. Besides plant use of nitrate, its reduction also occurs by bacterial action in oxygen-free soil and sediments. Reduced nitrogen can however be formed in a different way in the soil, where bacteria and plants work together. Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria in aerated soils provide an oxygen-free environment for their oxygen-sensitive nitrogenase within nodules induced on the roots of legumes, such as clover and alfalfa (Marschner, 1997). BNF symbioses also occur in many trees associated with gram-positive Frankia.

The preindustrial nitrogen cycle could be characterized as a careful preservation of the very low amount of Nr available in nature. Nr is created and distributed by natural processes such as forest fires, lightning, volcanic eruptions, and biological nitrogen fixation (Smil, 2001; Reid et. al., 2005). The natural production of Nr is estimated by many authors to be around 125 (Tg) N per year, with 5 Tg from lightning and 120 Tg from biological nitrogen fixation (Galloway et al., 2003, 2008; Schlesinger, 2009).

Human-induced Changes of the Nitrogen Cycle

In addition to the natural formation of Nr, there are also significant geophysical and anthropogenic sources. The Haber-Bosch process is the first high-pressure industrial process that fixes nitrogen to ammonia on a large scale and “helps” nature increase plant growth (Smil, 2001). The second largest bulk industrial nitrogen feedstock, nitric acid, lies at the other extreme of the redox series. Ammonia is oxidized to produce nitric acid in the Oswald process, named after its discoverer Wilhelm Oswald. It makes good chemical sense that the principal industrial nitrogen compounds lie at opposite ends of the redox series (valencies of −3 for ammonia to +5 for nitrate). With these two reagents, it is ultimately possible to synthesize any desired compound with an intermediate oxidation state for nitrogen. The major use for nitrogen compounds is as fertilizers. Industrial nitrogen fixation is estimated to be 125 Tg/yr, of which 82% is for fertilizer production, and the remaining is for industrial use and explosives (Galloway et al., 2008).Fertilizer application to cultivated plants is more than double the natural amount of BNF. Cultivation of arable land has increased BNF by about 40 million metric tons per year (Tg/yr) (Galloway et al., 2008). Fossil fuel combustion adds another 25 Tg/yr of oxidized nitrogen, released to the atmosphere (Galloway et al., 2008; Schlesinger, 2009). For 2005 the total human-induced Nr added up to 170 (Schlesinger, 2009) to 187 Tg/yr (Galloway et al., 2008). Adding the naturally produced Nr results in about 300 Tg/yr generated globally.

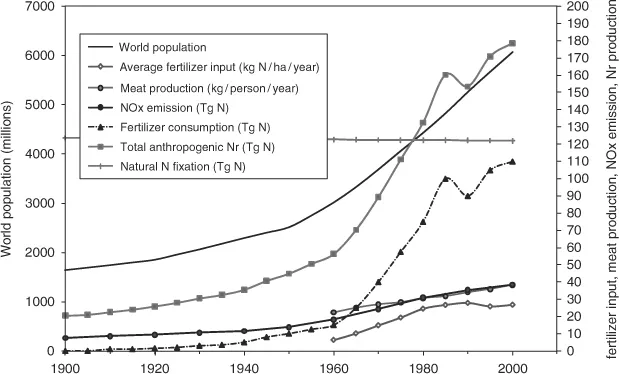

Figure 1.2 shows the increase in human-induced Nr production since the beginning of the last century. By 1980 human Nr production became larger than natural production and, until 1980, the production increase was higher than the population increase. This changed after the 1990s when the economic situation in Eastern Europe affected agricultural production in that area. Since then the increase in fertilizer use matches the population growth. One can conclude that there is room for improvement in the fertilizer use efficiency and at the same time, that as world population grows, fertilizer use will grow at least at the same rate if no measures are taken.

Figure 1.2. Changes in global Nr production (modified from Reid et al., 2005; Erisman et al., 2008; Van Aardenne, 2001).

Too Much or Too Little of a Good Thing

There are two major problems with Nr: some regions of the world have too little and others too much. In the latter case burning of fossil fuel and inefficient incorporation of nitrogen into food has resulted in a large number of major human health and ecological problems. In the N-deficient areas, too little food, especially proteins, will cause more malnutrition eventually leading to increased mortality. The rate of change in N distribution is enormous and probably greater than that for other ecological problems. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), currently more than 1 billion people, especially in the south of the world, suffer from malnutrition. In those regions of the world where there is not enough food, nitrogen availability through fertilizers might be the limiting factor, apart from availability of water and other nutrients. Obviously, fertilizer distribution depends on infrastructure and social and/or economic factors.

In Europe, the US, and more recently in China, food production is stimulated by government support (e.g., by subsidizing fertilizers). This has created a shift from good nutrient management to industrialized food production with appreciable waste of inexpensive nitrogen and its release to the environment. Global nitrogen fertilizer production occurs in a limited part of the globe, but nitrogen is transported to other regions in the form of food and feed and through the air (NOx). Human creation and use of Nr (see Figure 1.2) has created a new nitrogen cycle, especially because the efficiency of N use has decreased along with its increased, but less efficient, production. The energy efficiency of nitrogen in fossil fuel is, in essence, zero, because the NOx formed during combustion is an unwanted by-product and has no function in the production of energy. In agriculture Nr is added in the form of fertilizer to increase crop yield. However, only 5–10% of fertilizer N ends up in our food depending on the type of food (meat or vegetables), the agricultural system, and management (Smil, 2001; UNEP, 2007). Meat production is an additional inefficient step in the food N chain with further Nr losses to the environment (Steinfeld et al., 2006). Most of the nitrogen lost to the environment is through air emissions (ammonia, nitrogen oxides, nitrous oxide) and water (NO3 run-off and/or leaching), in addition to that returned to the atmosphere as N2 (Galloway et al., 2003). These losses cascade through the different environment compartments, exchanging forms and contributing to many different effects in time and space. This is called the “cascade effect of nitrogen” (Galloway et al., 2003).

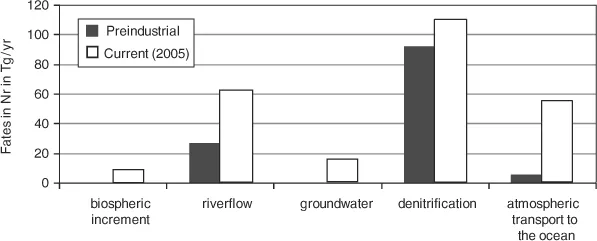

Schlesinger (2009) estimated that the fates of natural Nr were mainly conversion to N2 via denitrification (92 of the 125 Tg/yr), the other major flux being river flow. Figure 1.3 shows the increase in the fates of Nr from the preindustrial era to the current situation. For anthropogenic nitrogen, the biospheric increment amounts to 9 Tg, river flow increment amounts to 35 Tg, groundwater leaching to 15 Tg, denitrification to 17 Tg, and atmospheric transport to the ocean to 48 Tg per year. The fate of anthropogenic nitrogen is therefore much less as N2 than the fate of natural nitrogen. These data are, however, highly uncertain as discussed in Galloway and others (2008). What is clear, though, is that the losses of Nr to the environment have increased substantially, especially in the areas of intensive fossil fuel use and agriculture.

Figure 1.3. Increase in the fates of Nr currently (2005) compared to preindustrial (Tg/y).

Anthropogenic disruptions in the nitrogen cycle have led to an 1,100% increase in the flux of nonreactive atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to Nr compounds. Once converted to a reactive state, nitrogen persists in the environment, “cascading” through various compounds (NH3, N2O, NOx, NO3), resulting in impacts such as the production of ground-level ozone, acidification, eutrophication, hypoxia, stratospheric ozone depletion, and climate change (Vitousek and Melillo 1997; Mansfield et al., 1998; Langan, 1999; Cowling et al., 2002; Galloway et al., 2003, 2008).

N-limitation and Biodiversity

In the natural environment nitrogen is a limiting factor for growth, leading to a rich biodiversity of strategies for N acquisition, N “management,” and N “preservation.” Trees, for example, retreat their leaf nitrogen before senescence. If Nr becomes increasingly available, the fast growing species, no longer growth limited (provided other nutrients and water are sufficiently available), will overgrow slow-growing species resulting in serious loss of biodiversity, algal blooms, hypoxic zones, etc. (e.g., Goulding et al., 1998; Bobbink, 2004; Stevens et al., 2004; Dise and Stevens, 2005; Phoenix et al., 2006; Klimek et al., 2007). The effects due to high N deposition extend to fauna, a notable example of which is the disappearance of the red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio) in coastal dunes of the Netherlands and in other parts of Western Europe. The red-backed shrike is a good indicator of fauna diversity, since its breeding success depends highly on the availability of large insects and small vertebrates (Beusink et al., 2003). Evidence for serious adverse effects on faunal species diversity and marine systems exists, but the level of scientific understanding is rather low.

The negative impacts of Nr emissions include eutrophication of seminatural ecosystems and surface waters, soil acidification, nitrate pollution of groundwater, particulate formation leading to impacts on human health, and alterations of the earth’s radiation balance, such as ozone formation leading to effects on humans and vegetation, and to climate change when N is transformed into nitrous oxide, one of the most important greenhouse gases (e.g., Galloway, 1998; Galloway and Cowling, 2002; Matson et al., 2002; Galloway et al., 2003). Although the effects ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Halftitle page

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Section 1 The Nitrogen Cycle

- Section 2 Plant-Soil Microbe Interactions

- Section 3 Epi- and Endo-Phytic Microbes

- Section 4 Arthropods

- Section 5 Environmental Signalling in N Acquisition

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ecological Aspects of Nitrogen Metabolism in Plants by Joe C. Polacco,Christopher D. Todd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.