- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dermatology

About this book

Lecture Notes: Dermatology provides all the necessary information, within one short volume, to achieve a thorough understanding of skin structure and function, and the practical aspects of disease management.

Presented in a user-friendly format, combining readability with high quality illustrations, this tenth edition has been revised to reflect recent advances in knowledge of skin diseases and developments in therapy, and features a brand new chapter on Dermatological Emergencies.

Key features include:

- Numerous figures and tables help distil the information you need for revision purposes

- MCQs and 15 new clinical case studies for self assessment

- Glossary of dermatological terms

Whether you need to develop or refresh your knowledge of dermatology, Lecture Notes: Dermatology presents 'need to know' information for all those involved in treating skin disorders.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Structure and function of the skin, hair and nails

Skin, skin is a wonderful thing,

Keeps the outside out and the inside in.

Keeps the outside out and the inside in.

It is essential to have some background knowledge of the normal structure and function of any organ before you can hope to understand the abnormal. Skin is the icing on the anatomical cake, it is the decorative wrapping paper, and without it not only would we all look rather unappealing, but also a variety of unpleasant physiological phenomena would bring about our demise. You have probably never contemplated your skin a great deal, except in the throes of narcissistic admiration, or when it has been blemished by some disorder, but hopefully by the end of this first chapter you will have been persuaded that it is quite a remarkable organ, and that you are lucky to be on such intimate terms with it.

Skin structure

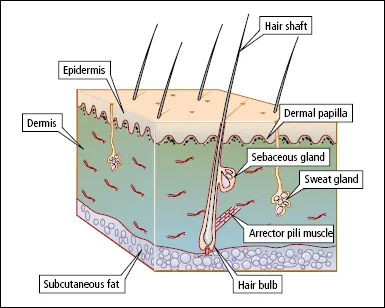

The skin is composed of two layers, the epidermis and the dermis (Figure 1.1). The epidermis, which is the outer layer, and its appendages (hair, nails, sebaceous glands and sweat glands), are derived from the embryonic ectoderm. The dermis is of mesodermal origin.

The epidermis

The epidermis is a stratified squamous epithelium, with several well-defined layers. The principal cell type is known as a keratinocyte. Keratinocytes, produced by cell division in the deepest layer of the epidermis (basal layer), are carried towards the skin surface, undergoing in transit a complex series of morphological and biochemical changes known as terminal differentiation (keratinization) to produce the surface layer of tightly packed dead cells (stratum corneum or horny layer) which are eventually shed. In health the rate of production of cells matches the rate of loss so that epidermal thickness is constant. Epidermal kinetics are controlled by a number of growth stimulators and inhibitors.

The components of this differentiation process are under genetic control and mutations in the controlling genes are responsible for a variety of diseases.

So-called intermediate filaments, present in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells, are a major component of the cytoskeleton. They contain a group of fibrous proteins known as keratins, each of which is the product of a separate gene. Pairs of keratins are characteristic of certain cell types and tissues. The mitotically active keratinocytes in the basal layer express the keratin pair K5/K14, but during the differentiation process expression of K5/K14 is down-regulated and that of K1/K10 is induced.

Figure 1.1 The structure of the skin.

As cells reach the higher layers of the epidermis, keratin filaments aggregate into keratin fibrils under the influence of a protein known as filag-grin (filament-aggregating protein)—this is derived from its precursor profilaggrin, present in keratohyalin granules which constitute the granules in the granular layer. Derivatives of the proteolysis of filaggrin are major components of natural moisturizing factor (NMF) which is important in the maintenance of epidermal hydration. Loss-of function mutations in FLG, the gene encoding filaggrin, underlie ichthyosis vulgaris and strongly predispose to atopic eczema; carriers of these mutations have reduced levels of NMF in the stratum corneum.

In the final stages of terminal differentiation, the plasma membrane is replaced by the cornified cell envelope, composed of several proteins the production of which is also under genetic control. Cells that have developed this envelope and have lost their nucleus and organelles constitute the corneocytes of the stratum corneum.

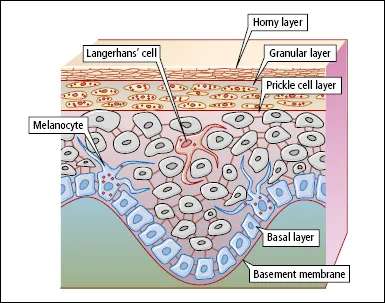

Look at the layers more closely (Figure 1.2). The basal layer, which is one to three cells thick, is anchored to a basement membrane (see below) that lies between the epidermis and dermis. Interspersed among the basal cells are melanocytes—large dendritic cells derived from the neural crest—that are responsible for melanin pigment production. Melanocytes contain cytoplasmic organelles called melanosomes, in which melanin is synthesized from tyrosine. The melanosomes migrate along the dendrites of the melanocytes and are transferred to the keratinocytes in the prickle cell layer. In white people the melanosomes are grouped together in membrane-bound melanosome complexes, and they gradually degenerate as the keratinocytes move towards the surface of the skin. The skin of black people contains the same number of melanocytes as that of white people, but the melanosomes are larger, remain separate and persist through the full thickness of the epidermis. The main stimulus to melanin production is ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Melanin protects the cell nuclei in the epidermis from the harmful effects of UV radiation. A suntan is a natural protective mechanism, not some God-given cosmetic boon created so that you can impress the neighbours on your return from an exotic foreign trip! Unfortunately, this does not appear to be appreciated by the pale, pimply, lager-swilling advert for British manhood who dashes onto the beach in Ibiza and flash fries himself to lobster thermidor on day one of his annual holiday.

Skin neoplasia is extremely uncommon in dark-skinned races because their skin is protected from UV damage by the large amounts of melanin that it contains. However, individuals with albinism are predisposed to skin cancer because their production of melanin is impaired and they are therefore without its protective influence.

Above the basal layer is the prickle cell/spinous layer. This acquires its name from the spiky appearance produced by the intercellular bridges (desmosomes) that connect adjacent cells. Important in cell–cell adhesion are several protein components of desmosomes (including cadherins [desmogleins and desmocollins] and plakins). Production of these is genetically controlled, and abnormalities have been detected in some human diseases.

Figure 1.2 The epidermis.

Scattered throughout the prickle cell layer are Langerhans’ cells. These dendritic cells contain characteristic racquet-shaped ‘Birbeck’ granules. Langerhans’ cells are probably modified macrophages, which originate in the bone marrow and migrate to the epidermis. They are the first line of immunological defence against environmental antigens (see below).

Above the prickle cell layer is the granular layer, which is composed of flattened cells containing the darkly staining keratohyalin granules. Also present in the cytoplasm of cells in the granular layer are organelles known as lamellar granules (Odland bodies). These contain lipids and enzymes, and they discharge their contents into the intercellular spaces between the cells of the granular layer and stratum corneum—providing the equivalent of ‘mortar’ between the cellular ‘bricks’, and contributing to the barrier function of the epidermis.

The cells of the stratum corneum are flattened, keratinized cells that are devoid of nuclei and cytoplasmic organelles. Adjacent cells overlap at their margins, and this locking together of cells, together with intercellular lipid, forms a very effective barrier. The stratum corneum varies in thickness according to the region of the body. It is thickest on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. The stratum corneum cells are gradually abraded by daily wear and tear. If you bathe after a period of several days’ avoidance of water (a house without central heating, in mid-winter, somewhere in the Northern Hemisphere, is ideal for this experiment), you will note that as you towel yourself you are rubbing off small balls of keratin—which has built up because of your unsanitary habits. When a plaster cast is removed from a fractured limb after several weeks in situ there is usually a thick layer of surface keratin, the removal of which provides hours of absorbing occupational therapy.

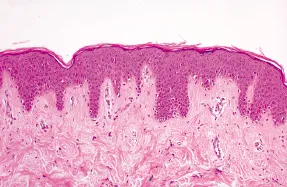

Figure 1.3 shows the histological appearance of normal epidermis.

The basement membrane zone

This is composed of a number of layers, and it is important to have some knowledge of these because certain diseases are related to abnormalities in the layers. The basic structure is shown in Figure 1.4. Basal keratinocytes are attached by hemidesmosomes to the epidermal side of the membrane, and these have an important role in maintaining adhesion between the epidermis and dermis. The basement membrane is composed of three layers: lamina lucida (uppermost), lamina densa and lamina fibroreticularis. A system of anchoring filamentsconnects hemidesmosomes to the lamina densa, and anchoring fibrils, which are closely associated with collagen in the upper dermis, connect the lamina densa to the dermis beneath.

The hemidesmosome/anchoring filament region contains autoantigens targeted by autoantibodies in immunobullous disorders (including bullous pemphigoid, pemphigoid gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid and linear IgA bullous dermatosis—see Chapter 14), hence the subepidermal location of blistering in these disorders.

Figure 1.3 Section of skin stained with haematoxylin and eosin, showing the appearance of a normal epidermis. ‘Rete ridges’ (downward projections of the epidermis) interdigitate with ‘dermal papillae’ (upward projections of the dermis).

The inherited blistering diseases (see Chapter 14) occur as a consequence of mutations in genes responsible for components of the basement membrane zone, e.g. epidermolysis bullosa simplex, in which splits occur in the basal keratinocytes, is related to mutations in genes coding for keratins 5 and 14, and dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, in which blistering occurs immediately below the lamina densa, is related to mutations in a gene coding for type VII collagen, the major component of anchoring fibrils.

Epidermal appendages

The eccrine and apocrine sweat glands, the hair and sebaceous glands, and the nails, constitute the epidermal appendages.

Eccrine sweat glands

Eccrine sweat glands are important in body temperature regulation. A human has between two and three million eccrine sweat glands covering almost all the body surface. They are particularly numerous on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Each consists of a secretory coil deep in the dermis, and a duct that conveys the sweat to the surface. Eccrine glands secrete water, electrolytes, lactate, urea and ammonia. The secretory coil produces isotonic sweat, but sodium chloride is reabsorbed in the duct so that sweat reaching the surface is hypotonic. Patients with cystic fibrosis have defective reabsorption of sodium chloride, and rapidly become salt depleted in a hot environment. Eccrine sweat glands are innervated by the sympathetic nervous system, but the neurotransmitter is acetylcholine.

Figure 1.4 Structure of the basement membrane zone.

Apocrine sweat glands

Apocrine sweat glands are found principally in the axillae and anogenital region. Specialized apocrine glands include the wax glands of the ear and the milk glands of the breast. Apocrine glands are also composed of a secretory coil and a duct, but the duct opens into a hair follicle, not directly on to the surface of the skin. Apocrine glands produce an oily secretion containing protein, carbohydrate, ammonia and lipid. These glands become active at puberty, and secretion is controlled by adrenergic nerve fibres. Pungent axillary body odour (axillary bromhidrosis) is the result of the action of bacteria on apocrine secretions. In some animals apocrine secretions are important sexual attractants, but the average human armpit provides a different type of overwhelming olfactory experience.

Hair

Hairs grow out of tubular invaginations of the epidermis known as follicles, and a hair follicle and its associated sebaceous glands are referred to as a ‘pilosebaceous unit’. There are three types of hair: fine, soft lanugo hair is present in utero and is shed by the eighth month of fetal life; vellus hair is the fine downy hair that covers most of the body except those areas occupied by terminal hair; and thick and pigmented terminal hair occurs on the scalp, eyebrows and eyelashes before puberty—after puberty, under the influence of androgens, secondary sexual terminal hair develops from vellus hair in the axillae and pubic region, and on the trunk and limbs in men. On the scalp, the reverse occurs in male-pattern balding—terminal hair becomes vellus hair under the influence of androgens. In men, terminal hair on the body usually increases in amount as middle age arrives, and hairy ears and nostrils, and bushy eyebrows, are puzzling accompaniments of advancing years. One struggles to think of any biological advantage conferred by exuberant growth of hair in these sites.

Hair follicles extend into the dermis at an angle (see Figure 1.1). A small bundle of smooth muscle fibres, the arrector pili muscle, is attached to the side of the follicle. Arrector pili muscles are supplied by adrenergic nerves, and are responsible for the erection of hairs in the cold or during emotional stress (‘goose flesh’, ‘goose pimples’, horripilation). The duct of the sebaceous gland enters the follicle just above the point of attachment of the arrector pili muscle. At the lower end of the follicle is the hair bulb, part of which, the hair matrix, is a zone of rapidly dividing cells that is responsible for the formation of the hair shaft. Hair pigment is produced by melanocytes in the hair bulb. Cells produced in the hair bulb become densely packed, elongated and arranged parallel to the long axis of the hair shaft. They gradually become keratinized as they ascend in the hair follicle.

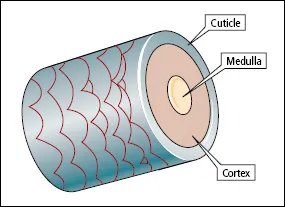

The main part of each hair fibre is the cortex, which is composed of keratinized spindle-shaped cells (Figure 1.5). Terminal hairs have a central core known as the medulla, consisting of specialized cells that contain air spaces. Covering the cortex is the cuticle, a thin layer of cells that overlap like the tiles on a roof, with the free margins of the cells pointing towards the tip of the hair. The cross-sectional shape of hair varies with body site and race. Negroid hair is distinctly oval in cross-section, and pubic, beard and eyelash hairs have an oval cross-section in all racial types. Caucasoid hair is moderately elliptical in cross section and mongoloid hair is circular.

The growth of each hair is cyclical—periods of active growth alternate with resting phases. After each period of active growth (anagen) there is a short transitional phase (catagen), followed by a resting phase (telogen), after which the follicle reactivates, a new hair is produced and the old hair is shed. The duration of these cyclical phases depends on the age of the individual and the location of the follicle on the body. The duration of anagen in a scalp follicle is genetically determined, and ranges from 2 to more than 5 years. This is why some women can grow hair down to their ankles, whereas most have a much shorter maximum length. Scalp hair catagen lasts about 2 weeks and telogen from 3 months to 4 months. The daily growth rate of scalp hair is approximately 0.45 mm. The activity of each follicle is independent of that of its neighbours, which is fortunate, because, if follicular activity were synchronized, as it is in some animals, we would be subject to periodic moults, thus adding another dimension to life’s rich tapestry. At any one time approximately 85% of scalp hairs are in anagen, 1% in catagen and 14% in telogen. The average number of hairs shed daily is 100. In areas other than the scalp anagen is relatively short—this is also fortunate, because, if it were not so, we would all be kept busy clipping eyebrows, eyelashes and nether regions.

Figure 1.5 The structure of hair.

It is a myth that shaving increases the rate of growth of hair and that it encourages the development of ‘thicker’ hair; nor does hair continue growing after death—shrinkage of soft tissues around the hair produces this illusion.

Human hair colour is principally dependent on two types of melanin: eumelanins in black and brown hair, and phaeomelanins in red, auburn and blond hair.

Greying of hair (canities) is the result of a decrease in tyrosinase activity in the melanocytes of the hair bulb. The age of onset of greying is genetically determined, but other factors may be involved such as autoimmunity—premature greying of the hair is a recognized association of pernicious anaemia. The phenomenon of ‘going white overnight’ has been attributed to severe psychological stress—it is said that the hair of Thomas Moore and Marie Antoinette turned whi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributor

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Structure and function of the skin, hair and nails

- 2: Approach to the diagnosis of dermatological disease

- 3: Bacterial and viral infections

- 4: Fungal infections

- 5: Ectoparasite infections

- 6: Acne, acneiform eruptions and rosacea

- 7: Eczema

- 8: Psoriasis

- 9: Benign and malignant skin tumours

- 10: Naevi

- 11: Inherited disorders

- 12: Pigmentary disorders

- 13: Disorders of the hair and nails

- 14: Bullous disorders

- 15: Miscellaneous erythematous and papulosquamous disorders, and light-induced skin diseases

- 16: Vascular disorders

- 17: Connective tissue diseases

- 18: Pruritus

- 19: Systemic disease and the skin

- 20: Skin and the psyche

- 21: Cutaneous drug reactions

- 22: Treatment of skin disease

- 23: Emergency dermatologys

- Case study questions

- Multiple choice questions

- Answers to case study questions

- Answers to multiple choice questions

- Glossary of dermatological terms

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dermatology by Robin Graham-Brown,Tony Burns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Dermatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.