![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1

Developmental Systems, Nature-Nurture, and the Role of Genes in Behavior and Development

On the legacy of Gilbert Gottlieb

Kathryn E. Hood, Carolyn Tucker Halpern, Gary Greenberg and Richard M. Lerner

The histories of both developmental and comparative science during the 20th century attest unequivocally to the fact that the theory and research of Gilbert Gottlieb – along with the work of such eminent colleagues as T. C. Schneirla (1956, 1957), Zing-Yang Kuo (1967; Greenberg & Partridge, 2000), Jay Rosenblatt (e.g., this volume), Ethel Tobach (1971, 1981), Daniel Lehrman (1953, 1970), Howard Moltz (1965), and George Michel (e.g., this volume) – may be seen as the most creative, integrative, generative, and important scholarship in the field (cf. Gariépy, 1995). For more than a third of a century Gilbert Gottlieb (e.g., 1970, 1997; Gottlieb, Wahlsten, & Lickliter, 2006) provided an insightful theoretical frame, and an ingenious empirical voice, to the view that:

an understanding of heredity and individual development will allow not only a clear picture of how an adult animal is formed but that such an understanding is indispensable for an appreciation of the processes of evolution as well [and that] the persistence of the nature-nurture dichotomy reflects an inadequate understanding of the relations among heredity, development, and evolution, or, more specifically, the relationship of genetics to embryology. (Gottlieb, 1992, p. 137)

Gottlieb attempted to heal the Cartesian nature-nurture split between biological and social science (Overton, 2006) by developing an ingenious – and what would come to be seen as the cutting-edge – theoretical conception of the dynamic and mutually influential relations, or “coactions,” among the levels of organization comprising the developmental system, that is, levels ranging from the genetic through the sociocultural and historical. In devising a developmental systems theoretical perspective about the sources of development, and bringing rigorous comparative developmental data to bear on the integrative concepts involved in his model of mutually influential, organism ↔ context relations, Gottlieb’s theory and research (e.g., Gottlieb, 1991, 1992, 1997, 1998, 2004; Gottlieb et al., 2006) became the exemplar in the last decades of the 20th century and into the first portion of the initial decade of the 21st century of the postmodern, relational metatheory of developmental science (Overton, 1998, 2006).

Gottlieb presents an integrative, developmental systems theory of evolution, ontogenetic development, and – ultimately – causality. Gottlieb argued that “The cause of development – what makes development happen – is the relationship of the components, not the components themselves. Genes in themselves cannot cause development any more than stimulation in itself can cause development” (Gottlieb, 1997, p. 91). Similarly, he noted that “Because of the emergent nature of epigenetic development, another important feature of developmental systems is that causality is often not ‘linear’ or straightforward” (Gottlieb, 1997, p. 96).

Gottlieb offered, then, a probabilistic conception of epigenesis, one that constitutes a compelling alternative to views of development that rest on what he convincingly argued was a counterfactual, split, and reductionist nature-nurture conception (see Overton, 2006). His theory, and the elegant data he generated in support of it, integrate dynamically the developmental character of the links among genes, behavior, and the multiple levels of the extra-organism context – the social and physical ecology – of an individual’s development (see too Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 2005; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Ford & Lerner, 1992; Lerner, 2002). In sum, Gottlieb’s work has influenced several generations of comparative and developmental scientists to eschew simplistic, conceptually reductionist, and split (i.e., nature as separate from nurture) conceptions of developmental process and to think, instead, systemically and, within the context of rigorous experimental and/or longitudinal studies, to attend to the dynamics of mutually influential organism ↔ context relations. His work has had and continues to have a profound impact on theory and research in diverse domains of science pertinent to the development of organisms.

Gottlieb’s career was dedicated to providing rigorous experimental evidence to bear on this integrative approach to understanding these dynamics of organism and context relations. His work constitutes a major scientific basis for rejecting the reductionism and counterfactual approach to understanding the links among genes, behavior, and development, for example, as found in behavioral genetics, sociobiology or evolutionary psychology, and other reductionist approaches.

Gottlieb was a preeminent developmental scientist and theoretician who, throughout his career, battled against scientific reductionism and advocated an open, holistic, multilevel systems approach for understanding development. His developmental systems theory grew from decades of his research, which covered the range of emerging and continuing issues in understanding the dynamic fusion of biology and ecology that constitutes the fundamental feature of the developmental process (e.g., Gottlieb, 1997, 1998). In particular, he challenged the deterministic concept of an innate instinct, and offered instead his generative conception of probabilistic epigenesis as a basis for shaping behavioral development as well as evolutionary change.

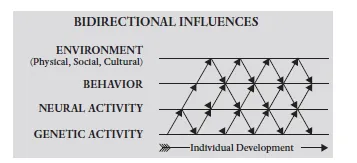

Gottlieb’s contention is that development proceeds in concert with influences from all levels of the organism and the context. “A probabilistic view of epigenesis holds that the sequence and outcomes of development are probabilistically determined by the critical operation of various endogenous and exogenous stimulative events” (Gottlieb, 2004, p. 94). The bidirectional and coactional processes occurring within and across levels of a developmental system were succinctly captured in his figurative systems framework (Gottlieb, 1992), shown in Figure 1.1.

In addition to his own empirical research, Gottlieb avidly searched across disciplines for observations and research findings that exemplified his concepts, that is, the co-actions in the model depicted in Figure 1.1.

The Goals of the Handbook

The Handbook of Developmental Science, Behavior, and Genetics commemorates the historically important and profound contributions made by Gilbert Gottlieb across a scholarly career spanning more than four decades. Gottlieb was preparing this Handbook when his untimely death in 2006 brought his work on this project to a halt. However, with the permission and support of the Gottlieb family, the editors of this work have decided to complete Gottlieb’s “last book,” which was designed to bring together in one place the cutting-edge theory, research, and methodology that provide the modern scientific understanding of the integration of levels of organization in the developmental system – ranging from genes through the most macro levels of the ecology of development. The dynamics of this integration constitute the fundamental, relational process of development.

Accordingly, the scholarship that Gottlieb arranged to have included in this Handbook will present to biological, comparative, and developmental scientists – both established and in training – the cutting-edge of contemporary theory and research underscoring the usefulness of the synthetic, developmental systems theory approach to understanding the mutually influential relations among genes, behavior, and context that propel the development of organisms across their life spans.

In sum, we hope that this Handbook will be a watershed reference for documenting the current status of comparative and developmental science and for providing the foundation from which future scientific progress will thrive. The organization and chapters of the Handbook actualize its contribution. It is useful, therefore, to explain how the structure and content of the Handbook instantiate and extend Gottlieb’s scholarship and vision.

The Plan of this Handbook

We are grateful that Evelyn Fox Keller provides a foreword to this Handbook, one that so well frames its contribution to developmental and comparative science. Keller notes the importance for science of the innovative explanatory model devised by Gottlieb, what he termed the “developmental point of view.” She explains how this conception requires a “relational” (“coactive” and “bidirectional”) view of causality; an appreciation of the continuity between prenatal and postnatal, innate and acquired; the recognition that epigenesis is ongoing, multifaceted, not predetermined but, instead, highly dependent on experience (what Gottlieb described as constituting a probabilistic process), and involving a shift in focus from population statistics to the study of individual trajectories. Given the centrality in Gottlieb’s work of refining this developmental point of view, after this opening chapter we reprint a key paper authored by Gottlieb, one that explains his conception of probabilistic epigenesis through discussing what are normally occurring environmental and behavioral influences on gene activity.

To place this view into its historical and theoretical contexts, Part II of the Handbook is devoted to discussions of the theoretical foundations for the developmental study of behavior and genetics. James Tabery and Paul E. Griffiths provide a historical overview of traditional behavior genetics. They note that historical disputes between quantitative behavioral geneticists and developmental scientists stem largely from differences in methods and conceptualizations of key constructs, and in epistemological disagreement about the relevance of variation seen in populations. In turn, Mae Wan Ho revisits the links between development and evolution by discussing developmental and genetic change over generations. She reviews recent evidence in support of the idea that evolutionary novelties arise from non-random developmental changes defined by the dynamics of the epigenetic system; and shows how the organism participates in shaping its own development and adaptation of the lineage.

Douglas Wahlsten next discusses the assumptions and pitfalls of traditional behavior genetics. He notes that the concept of additivity of genes and environment, key to heritability analysis, is in conflict with contemporary views about how genes function as a part of a complex developmental system. Molecular genetic experiments indicate that genes act at the molecular level but do not specify phenotypic outcomes of development.

Next, George F. Michel discusses the connections between environment, experience, and learning in the development of behavior. He focuses on the concept of “Umwelt” and the meaning of gen–environment interaction in behavioral development.

The final chapter in this section of the book, by Ty Partridge and Gary Greenberg, discusses contemporary ideas in physics and biology in Gottlieb’s psychology. The chapter reviews current ideas in biology, physiology, and physics and shows how they fit into Gottlieb’s developmental systems perspective. The concepts of increasing complexity with evolution and that of emergence are discussed in detail and offer an alternative to reductionist genetic explanations of behavioral origins.

Framed by these discussions of the theoretical foundations of Gottlieb’s view of how genes are part of the fused processes of organism ↔ context interactions that comprise the developmental system, Part III of the Handbook presents several empirical studies of behavioral development and genetics. Jay S. Rosenblatt discusses the mother as the developmental environment of the newborn among mammals and describes direct and indirect effects on newborn learning. His chapter provides a thorough, up-to-date discussion of maternal–young behavior among placental animals. The discussion is presented from both evolutionary and developmental perspectives. In the next chapter, Scott R. Robinson and Valerie Méndez-Gallardo provide data on fetal activity, amniotic fluid, and the epigenesis of behavior that, together, enable one to blur the “boundaries” of the organism.

Susan A. Brunelli, Betty Zimmerberg, and Myron A. Hofer discuss how family effects may be assessed through animal models of developmental systems. They provide data about the selective breeding of rats for differences in infant ultrasound vocalization related to separation stress. They find that later behaviors in each line reflect active and passive coping styles. Similarly, Kathryn E. Hood demonstrates how early and later experience alters alcohol preference in selectively bred mice. She reports that the developmental emergence of behavior often shows increasing complexity over time. Philosophical and empirical sources suggest that emergent complexity entails specific internal developmental sources as well as external constraints and opportunities.

In turn, Allyson Bennett and Peter J. Pierre discuss the contribution of genetic, neural, behavioral, and environmental influences to phenotypic outcomes of development. They report that nonhuman primate studies model the interplay between genetic and environmental factors that contribute to complex disorders. Such translational research incorporating genetic, neurobiological, behavioral, and environmental factors allows insight into developmental risk pathways and ultimately contributes to the prevention and treatment of complex disorders.

Expanding on the discussion of gene-environment interactions, Lesley J. Rogers discusses the social and broader ecological context of the interactive contributions of genes, hormones, and early experience to behavioral development. Her presentation expands upon her earlier critical discussions of issues of genetic determinism in the treatment of neural lateralization. She offers empirical support for an experiential, developmental interpretation of lateralization in vertebrates.

Lawrence V. Harper discusses the idea of epigenetic inheritance by noting that multiple sources of change in environment and organism collaborate to provide coordinated changes in physiology and behavior over the course of development. Many of these factors are not obvious, but may be effective in producing a fit of organism and environment. Carolyn Tucker Halpern discusses the significance of non-replication of gene-phenotype associations. She notes that the failure to replicate gene-phenotype associations continues to be a problem in newer work testing gene-environment interactions, and may be exacerbated in genome-wide association studies. She argues that, given the many layers of regulation between the genome and phenotypes, and the probabilistic nature of development, criteria for replication merit renewed attention.

The next chapter, by Robert Lickliter and Christopher Harshaw, explains how the ideas of canalization and malleability enable elucidation of the regulatory and generative roles of development in evolution. They review evidence from birds and mammals demonstrating that the developmental processes involved in producing the reliable reoccurrence (canalization) of phenotypes under species-typical conditions are the same as those involved in producing novel phenotypic outcomes (malleability) under species-atypical circumstances. In other words, canalization and malleability are not distinct developmental phenomena – both are products of the organism’s developmental system. As Gottlieb recognized, understanding the dynamics of canalization and malleability can contribute to a fuller understanding of phenotypic development and advance both developmental and evolutionary theory.

To document the breadth of the use of Gottlieb’s ideas to developmental and comparative science, Part IV of the Handbook presents chapters that illustrate applications of his theory and research to human development. For instance, extending to humans the ideas discussed in Part III about gene-environment interactions within the developmental system, Cathi B. Propper, Ginger A. Moore, and W. Roger Mills-Koonce discuss child development, temperament, and changes in individual physiological functioning. They use a developmental systems approach to explore the reciprocal influences of parent-infant interactions and candidate genes on the development of infant physiological and behavioral reactivity and regulation. They emphasize that appreciat...