eBook - ePub

Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics

Examining and Interpreting Forensic Evidence

Brian J. Heard

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics

Examining and Interpreting Forensic Evidence

Brian J. Heard

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The updated second edition of Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics includes recent developed analytical techniques and methodologies with a more comprehensive glossary, additional material, and new case studies. With a new chapter on the determination of bullet caliber via x-ray photography, this edition includes revised material on muzzle attachments, proof marks, non-toxic bullets, and gunshot residues. Essential reading for forensic scientists, firearms examiners, defense and prosecution practitioners, the judiciary, and police force, this book is also a helpful reference guide for undergraduate and graduate forensic science students.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics by Brian J. Heard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Forensic Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Firearms

1.1 A Brief History of Firearms

1.1.1 Early hand cannons

The earliest type of handgun was simply a small cannon of wrought iron or bronze, fitted to a frame or stock with metal bands or leather thongs. These weapons were loaded from the muzzle end of the barrel with powder, wad and ball. A small hole at the breech end of the barrel, the touch hole, was provided with a pan into which a priming charge of powder was placed. On igniting this priming charge, either with a hot iron or lighted match, fire flashed through the touch hole and into the main powder charge to discharge the weapon.

These early weapons could have been little more than psychological deterrents being clumsy, slow to fire and difficult to aim. In addition, rain or damp weather had an adverse effect on the priming charge making it impossible to ignite.

Their first reported use is difficult to ascertain with any degree of certainty, but a number of instances are reported in Spain between 1247 and 1311. In the records for the Belgian city of Ghent, there are confirmed sightings of the use of hand cannons in Germany in 1313. One of the earliest illustrations concerning the use of hand cannons appears in the fifteenth century fresco in the Palazzo Publico, Sienna, Italy.

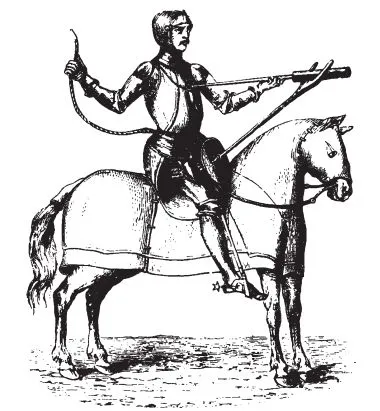

The first recorded use of the hand cannon as a cavalry weapon appeared in 1449 in the manuscripts of Marianus Jacobus. This shows a mounted soldier with such a weapon resting on a fork attached to the pommel of the saddle. It is interesting to note that the use of the saddle pommel to either carry or aim the hand guns could be the origin of the word ‘pistol’, the early cavalry word for the pommel of the saddle being ‘pistallo’.

Figure 1.1 Early hand cannon.

Combinations of the battle axe and hand cannon were used in the sixteenth century, and a number of these can be found in the Tower of London. One English development of this consisted of a large mace, the head of which had a number of separate barrels. At the rear of the barrels, a concealed chamber containing priming powder led to all the barrels. When the priming compound was ignited, all the barrels discharged at once.

1.1.2 The matchlock

This was really the first major advance in pistols as it enabled the weapon to be fired in one hand and also gave some opportunity to aim it as well.

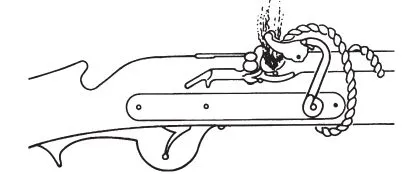

The construction of the matchlock was exactly the same as the hand cannon in that it was muzzle loaded and had a touch hole covered with a priming charge. The only difference was that the match, a slow-burning piece of cord used to ignite the priming charge, was held in a curved hook screwed to the side of the frame. To fire the gun, the hook was merely pushed forward to drop the burning end of the match into the priming charge. As these weapons became more sophisticated, the curved hook was embellished and took on the form of a snake and became known as the weapon’s serpentine.

Figure 1.2 Matchlock (by courtesy of the Association of Firearms and Toolmark Examiners).

Eventually, the tail of the serpentine was lengthened and became the forerunner of the modern trigger. Further refinements included the use of a spring to hold the head back into a safety position. The final refinement consisted of a system whereby when the tail of the serpentine was pulled, the match rapidly fell into the priming compound under spring pressure. This refinement, a true trigger mechanism, provided better ignition and assisted aiming considerably (Figure 1.2).

It was during the era of the matchlock that reliable English records appeared, and it is recorded that Henry VIII, who reigned from 1509 until 1547, armed many of his cavalry with matchlocks. The first true revolving weapon is also attributed to the period of Henry VIII and is on show in the Tower of London. This weapon consists of a single barrel and four revolving chambers. Each chamber is provided with its own touch hole and priming chamber which has a sliding cover. Although the actual lock is missing from the Tower of London weapon, its construction strongly suggests a single matchlock was used.

The major defect with the matchlock design was that it required a slowburning ‘match’ for ignition. As a result, it was of little use for surprise attack or in damp or rainy conditions.

1.1.3 The wheel lock

With the advent of the wheel lock the lighted match used in the matchlock was no longer necessary. This important innovation in the field of firearms design made ambush possible as well as making the firearm a practical weapon for hunting.

When fired from the shoulder, the wheel lock was often referred to as an arquebus from the shape of the butt which was often curved to fit the shoulder. Another name, strictly only for much heavier calibre weapons, was the hacquebut, which literally means ‘gun with a hook’. This referred to a hook projecting from the bottom of the barrel. This hook was placed over a wall, or some other object, to help take up the recoil of firing.

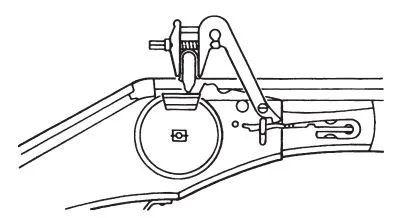

In its simplest form, the wheel lock consisted of a serrated steel wheel, mounted on the side of the weapon at the rear of the barrel. The wheel was spring-loaded via a chain round its axle with a small key or spanner similar to a watch drum (Figure 1.3). When the wheel was turned with a spanner, the chain wound round the axle and the spring was tensioned. A simple bar inside the lockwork kept the wheel from unwinding until released with the trigger. Part of the wheel protruded into a small pan, the flash pan or priming pan, which contained the priming charge for the touch hole. The serpentine, instead of containing a slow-burning match, had a piece of iron pyrite fixed in its jaws. This was kept in tight contact with the serrated wheel by means of a strong spring. On pressing the trigger, the bar was withdrawn from the grooved wheel which then turned on its axle. Sparks produced from the friction of the pyrite on the serrated wheel ignited the priming charge which in turn ignited the main powder charge and fired the weapon.

The wheel lock was a tremendous advance over the slow and cumbersome matchlock. It could be carried ready to fire and with a small cover over the flash pan, it was relatively impervious to all but the heaviest rain. The mechanism was, however, complicated and expensive, and if the spanner to tension the spring was lost, the gun was useless.

There is some dispute as to who originally invented the wheel lock, but it has been ascribed to Johann Kiefuss of Nuremberg, Germany in 1517.

Whilst the wheel lock reached an advanced stage of development in Germany, France, Belgium and Italy towards the close of the sixteenth century, England showed little interest in this type of weapon.

Figure 1.3 Wheel lock (by courtesy of the Association of Firearms and Toolmark Examiners).

Records show that the wheel lock was still being widely manufactured in Europe as late as 1640, but by the turn of the century, it was making way for its successor.

1.1.4 The snaphaunce

The snaphaunce first appeared around 1570, and was really an early form of the flintlock. This mechanism worked by attaching the flint to a spring-loaded arm. When the trigger is pressed, the cover slides off the flash pan, then the arm snaps forward striking the flint against a metal plate over the flash pan producing sparks to ignite the powder.

Whilst this mechanism was much simpler and less expensive than the wheel lock, the German gunsmiths, who tended to ignore the technical advances of other nationalities, continued to produce and improve upon the wheel lock up until the early eighteenth century.

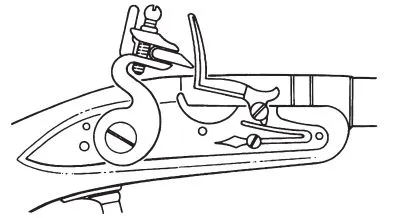

1.1.5 The flintlock

The ignition system which superseded that of the wheel lock was a simple mechanism which provided a spark by striking a piece of flint against a steel plate. The flint was held in the jaws of a small vice on a pivoted arm, called the cock. This was where the term to ‘cock the hammer’ originated.

The steel, which was called the frizzen, was placed on another pivoting arm opposite the cock, and the pan containing the priming compound was placed directly below the frizzen. When the trigger was pulled, a strong spring swung the cock in an arc so that the flint struck the steel a glancing blow. The glancing blow produced a shower of sparks which dropped into the priming pan igniting the priming powder. The flash produced by the ignited priming powder travelled through the touch hole, thus igniting the main charge and discharging the weapon.

The flintlock represented a great advance in weapon design. It was cheap, reliable and not overly susceptible to damp or rainy conditions. Unlike the complicated and expensive wheel lock, this was a weapon which could be issued in large numbers to foot soldiers and cavalry alike.

As is the case with most weapon systems, it is very difficult to pinpoint an exact date for the introduction of the flintlock ignition system. There are indications of it being used in the middle of the sixteenth century, although its first wide use cannot be established with acceptable proof until the beginning of the seventeenth century (Figure 1.4).

Three basic types of flintlock were made:

- Snaphaunce – a weapon with the mainspring inside the lock plate and a priming pan cover which had to be manually pushed back before firing.

- Miquelet – a weapon with the mainspring outside the lockplate, but with a frizzen and priming pan cover all in one piece. In this lock type, the pan cover was automatically pushed out of the way as the flint struck the frizzen.

- True flintlock – a weapon with a mainspring inside the lock plate and with the frizzen and priming pan cover in one piece. This also had a half-cock safety position enabling the weapon to be carried safely with the barrel loaded and the priming pan primed with powder. This system was probably invented by Mann Le Bourgeoys, a gunmaker for Louis XIII of France, in about 1615.

Figure 1.4 Flintlock (b y courtesy of the Association of Firearms and Toolmark Examiners).

Flintlock pistols, muskets (long-barrelled weapons with a smooth bore) and shotguns were produced with the flintlock mechanism. There was even a patent for flintlock revolvers issued in 1661.

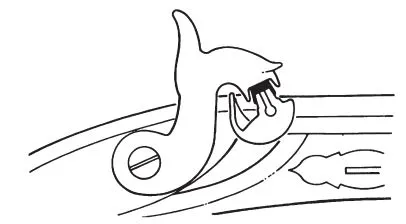

1.1.6 The percussion system

The flintlock continued to be used for almost 200 years and it was not until 1807 that a Scottish minister, Alexander John Forsyth, revolutionized the ignition of gunpowder by using a highly sensitive compound which exploded on being struck. This compound, mercury fulminate, when struck by a hammer, produced a flash strong enough to ignite the main charge of powder in the barrel. A separate priming powder and sparking system was now no longer required (Figure 1.5). With this invention, the basis for the self-contained cartridge was laid and a whole new field of possibilities was opened up.

Once this type of ignition, known as percussion priming, had been invented, it still took some time to perfect ways of applying it. From 1807 until 1814, a wide range of systems were invented for the application of the percussion priming system including the Forsyth scent bottle, pill locks, tube locks and the Pauly paper cap.

Figure 1.5 Percussion cap system (by courtesy of the Association of Firearms and Toolmark Examiners).

The final form, the percussion cup, was claimed by a large number of inventors. It is probably attributable to Joshua Shaw, an Anglo-American living in Philadelphia in 1814. Shaw employed a small iron cup into which was placed a small quantity of mercury fulminate. This was placed over a small tube, called a nip ple, projecting from the rear of the barrel. The hammer striking the mercury fulminate in the cup caused it to detonate and so send a flame down the nipple tube igniting the main charge in the barrel.

1.1.7 The pinfire system

Introduced to the United Kingdom at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 by Lefaucheux, the pinfire weapon was one of the earliest true breech-loading weapons using a self-...

Table of contents

Citation styles for Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics

APA 6 Citation

Heard, B. (2011). Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics (2nd ed.). Wiley. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1011746/handbook-of-firearms-and-ballistics-examining-and-interpreting-forensic-evidence-pdf (Original work published 2011)

Chicago Citation

Heard, Brian. (2011) 2011. Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics. 2nd ed. Wiley. https://www.perlego.com/book/1011746/handbook-of-firearms-and-ballistics-examining-and-interpreting-forensic-evidence-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Heard, B. (2011) Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics. 2nd edn. Wiley. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1011746/handbook-of-firearms-and-ballistics-examining-and-interpreting-forensic-evidence-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Heard, Brian. Handbook of Firearms and Ballistics. 2nd ed. Wiley, 2011. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.