![]()

Chapter 1

Origins

1.1 Plants—What are They?

We might simply define plants as photosynthetic eukaryotes—a description that would certainly include all the types of organisms that find their way into courses in botany or plant biology. However, as will become clear later in this chapter, such a definition brings together some very diverse groups whose common ancestor existed possibly as long ago as 1.6 billion years before the present time. These include glaucophytes (very simple unicellular aquatic organisms), all the different groups loosely known as algae and also the land plants, including the most advanced of these, the angiosperms (flowering plants), on which this book is mainly focused.

Charles Darwin, in a letter to Joseph Hooker, the Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, described the origin of flowering plants as an ‘abominable mystery’. They seemed at that time to appear in the fossil record without any obvious immediate precursors. Our understanding today, although somewhat more extensive than it was in Darwin's time, is still far from complete; the mystery is not yet completely solved. To appreciate this, it is necessary to go right back to the origin of cellular life and then of eukaryotes. It is a fascinating story.

1.2 Back to the Beginning

For much of the 20th century, our knowledge of the history of life on Earth went no further back than the dawn of the Cambrian period—‘only’ 550 million years ago. Fossils of quite sophisticated marine eukaryotes have been dated to that time and, during the Cambrian period itself, a very wide range of new lifeforms appeared. This flourishing of diversity in this period is known as the Cambrian explosion. However fascinating this is, it does not actually tell us of the earliest lifeforms.

Intense searches in pre-Cambrian rocks were conducted from the mid-1960s onward, but for many years failed to yield any fossils. However, one of those pivotal moments in science came when the American paleobiologist William Schopf identified fossil micro-organisms dating back 3.5 billion (i.e. 3.5 × 109) years. Whether or not these represent the oldest living things on Earth is still not clear. Some paleogeochemists have suggested that there is chemical evidence of life processes in rocks dating back 3.8 billion years, while others are of the opinion that the chemicals that supposedly indicate some form of metabolism at that time could equally have arisen by non-biogenic processes. Nevertheless, Schopf's discovery unlocked the ‘log-jam’ and, since then, many more fossils have been found in pre-Cambrian rocks. Furthermore, paleogeochemical analyses have given us a good idea of what conditions on Earth were like during this period. To this we can add detailed knowledge of the molecular biology and genetics of organisms living today. All this has enabled scientists to build up a picture of the main features of the evolution of living organisms during the pre-Cambrian.

So, life originated around 3.5 billion years ago (and possibly slightly earlier). The predominant, indeed probably the only, organisms then were similar to modern prokaryotes. Earth's atmosphere contained no free oxygen at that time, so these early bacteria were inevitably all anaerobic. Indeed, study of the properties of amino acids in modern anaerobic and aerobic organisms indicates strongly that the genetic code evolved under anaerobic conditions.

A good case has been made that the earliest cells were similar to today's Gram-positive bacteria and gave rise to two further lineages—the Gram-negative bacteria and the Archaea (or archaebacteria). The origin of the Archaea has thus been dated as occurring very early in the history of life. Fossil evidence indicates that photosynthetic bacteria (like modern cyanobacteria) first appeared about 2.8 billion years ago. The presence of photosynthetic organisms led to the ‘great oxidation event’ (between 2.2 and 2.45 billion years ago), which was bad news for anaerobic organisms because it generated free oxygen, which was (and still is to an extent) toxic to them. This selective pressure led to the evolution of aerobic organisms, capable of using oxygen in energy generation, probably at least two billion years ago.

1.3 Eukaryotes Emerge

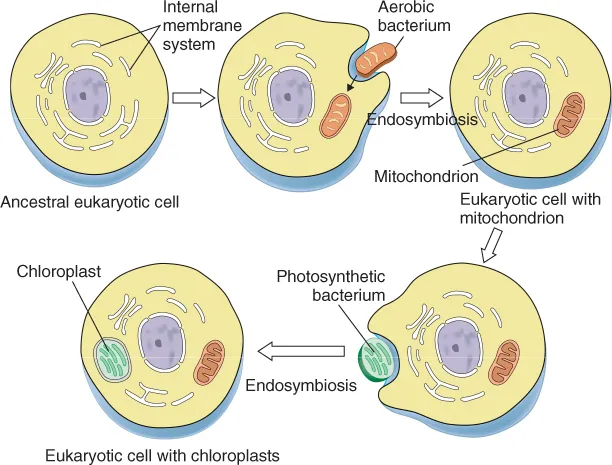

The idea that chloroplasts and mitochondria may have been derived from bacteria was first mooted in the 19th century, but it was not until the 1960s that the idea received wider attention. Based on her studies in cell biology, Lynn Margulis proposed specifically that mitochondria were derived in evolution from aerobic bacteria that had been engulfed by anaerobic bacteria, establishing the lineage that led to modern eukaryotes. According to this view, the inner membrane of the mitochondrion represents the original plasma membrane of the engulfed bacterium and the outer mitochondrial membrane represents the plasma membrane of the original host cell (see Figure 1.1). A second engulfment, this time of a photosynthetic (cyano)bacterium, led to the lineage(s) of photosynthetic eukaryotes and eventually to plants.

It is fair to say that, although some scientists embraced it enthusiastically, the endosymbiotic theory was not widely accepted when Margulis originally proposed it. Nevertheless, there was interest in what was called the ‘autonomy’ of chloroplasts and mitochondria. DNA from these organelles was unequivocally identified, as was the whole range of protein synthesis ‘machinery’. To all intents and purposes, these organelles appeared to be organisms within organisms—except that they had only a fraction of the number of genes needed to support independent life. If the endosymbiont hypothesis was correct, then transfer of genes from the endosymbiont to the host genome must have occurred during subsequent evolution.

Further analysis showed that a wide range of molecular biological features—including gene promoters, ribosome structure, sizes of particular types of RNA and the initiation of protein synthesis in plastids and mitochondria—resembled much more the equivalent features in bacteria than those of the major genetic system in the eukaryotic cells that contain the organelles. Further, the plastids of glaucophytes have a peptidoglycan wall, similar to the cell walls of cyanobacteria. All this is, of course, consistent with the endosymbiotic hypothesis and, by the time Margulis published her book Symbiosis in Cell Evolution in 1981, the hypothesis was accepted by the majority of biologists.

Further research during the past three decades has further confirmed the validity of the hypothesis, and it is now firmly stated that eukaryotes arose by the engulfment of an aerobic α-proteobacterium. Whether the ‘host’ cell was an archaean or a eubacterium is a matter for discussion. However, comparisons of biochemical mechanisms involved in DNA, RNA and protein synthesis, and of the sequences of genes and proteins, suggest a close relationship between the eukaryotic and archaebacterial clades. The authors of this book thus favour an archaebacterial origin for the eukaryotes, as shown in Figure 1.1, but there are some who believe that eukaryotes and archaebacteria are sister clades, having diverged from a common ancestor. Whichever of these two views one holds, there are still further problems to consider, of which we highlight three:

- First, there are some 60 clear differences between the organization, activity and structure of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. One of these differences is that prokaryotes are incapable of phagocytosis. However, the engulfment of a proteobacterial cell by an archaebacterial cell, a key part of the endosymbiont theory, would have been achieved by phagocytosis. So, either we envisage that a sub-group of ancient archaebacteria had already acquired some eukaryote-like features, such as phagocytosis, or that merger of two cells occurred by an unknown process.

- The second problem concerns another of these major differences, namely the sequestration of the main genome inside a complex organelle—the nucleus. With this came specific mechanisms for the division and segregation of the genome in the processes of mitosis and meiosis (the latter arising as part of the evolution of sexual reproduction). There has been much speculation on the evolution of the nucleus, but to date no really convincing hypothesis has emerged. The origin of this major feature of all eukaryotic cells remains totally mysterious.

- The third problem is that of the age of the eukaryotic lineage. The ‘molecular clock’ approach uses comparisons of sequences of genes and proteins in diverging lineages. Assumptions about rates of mutation, based on rates in living organisms, give an estimate of when lineages diverged from each other. This method places the origin of the eukaryotes at between 1.9 and 2.0 billion years ago, and there is some support for this dating from the fossil record. Most paleobiologists accept this dating, but there is a small group who contest it vigorously, suggesting that the eukaryotic lineage is much younger, dating back ‘only’ 800–900 million years. The authors of this book accept the majority view.

1.4 Photosynthetic Eukaryotes—The First ‘Plants’

The emergence of photosynthetic organisms and the resulting ‘great oxidation event’ provided the selective pressure for the emergence of aerobic organisms and the establishment of the eukaryotic lineage. However, we can say with some justification that the arrival of photosynthetic eukaryotes was even more significant. This large and now diverse array of autotrophic organisms, ranging from simple single-celled organisms to huge forest trees, has had a greater effect on the world's ecosystems than any other, and thus the engulfment of a photosynthetic cyanobacterium by an early aerobic eukaryote was a key step in the development of life on Earth.

Eukaryotes had split relatively rapidly into two groups: the unikonts (with one flagellumi), which gave rise to animals and fungi; and the bikonts (with two flagella). It was among the latter that photosynthetic ability was acquired, approximately 1.6 billion years ago. The Australian cell biologists Geoffrey McFadden and Giel van Dooren leave us in no doubt about the significance of this event:

‘This fusion of two cell lineages … brought the power of autotrophy to eukaryotes and descendants of this partnership have populated the oceans with algae and the land with plants, providing the world with most of its biomass’.

From this foundational step, there arose several of the groups that we included in our earlier loose definition of plants, including the green plants (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 : Abundance of green plants

The role of plants in contributing to biomass is c...