![]()

1

Introduction

R.P.C. MORGAN

National Soil Resources Institute, Cranfield University, Cranfield, Bedfordshire, UK

The movement of sediment and associated pollutants over the landscape and into water bodies is of increasing concern with respect to pollution control, prevention of muddy floods and general environmental protection. This concern exists whether the sediment is derived from farmland, road banks, construction sites, recreation areas or other sources. In today’s environment it is often considered of equal or even greater importance than the effects of loss of soil on-site, with its implications for declining agricultural productivity, loss of biodiversity and decreased amenity and landscape values. With the expected changes in climate over coming decades, there is a need to predict how environmental problems associated with sediment are likely to be affected so that appropriate management systems can be put in place.

Whilst it is possible to instrument a few individual farms and catchments in order to obtain the data to evaluate the current situation and propose best management practices, it is not feasible to study every location on the Earth’s surface in detail. Instead, evaluation and predictive tools need to be applied to assess current problems, predict future trends and provide a scientific base for policy and management decisions. Erosion models can fulfil this function provided that they are robust and used correctly. Despite, or maybe even because of, the vast amount of research over the last 30 years or more on erosion modelling, potential model-users are confronted with a multiplicity of models from which to choose, often with little guidance on which might be the best for particular circumstances or the steps required to apply a selected model to a given situation. Many models have been tested for only a limited range of conditions of climate, soils and land use, and little information is available to enable a user to assess in advance how well a model might perform under different conditions. Models range from empirical to physically- or process-based, and vary considerably in their complexity and the amount of data input required. Very little guidance is available on how accurate that data input has to be, or what effect different levels of accuracy can have on the accuracy of the model output. Further, sediment problems can exist at scales that range from a farmer’s field or a small construction site to the effects of sediment transport and deposition in small and large catchments. Somewhat limited information exists on the range of scales over which different models can operate successfully, leaving the user uncertain on whether a particular model is the most appropriate for a given scale. In the worst case, as a result of a lack of clear guidance, the user may choose a totally inappropriate model.

Users can obtain a list of the leading soil erosion models from the Internet site http://soilerosion.net/doc/models_menu.html. Links are provided to other sites associated specifically with each model from which the software can be downloaded along with the user manual. Whilst the majority of the links are valid and the site is a useful starting point for finding out what models exist, there are some links which are out-of-date and either do not work or are no longer the most appropriate. Clearly no such site can be fully comprehensive, and there will inevitably be some models which are not included. Table 1.1 lists the models which are used in this Handbook together with details of published sources and, where they exist, relevant Internet sites. Knowing which models are available is only a starting point. As indicated above, the user needs advice on how well the models perform and the conditions to which they can be applied. Previous experience with the models is extremely valuable, particularly where the output of several models is compared for the same conditions. Boardman and Favis-Mortlock (1998) discussed the performance of various models when applied to common sets of data at a hillslope scale, and De Roo (1999) presented the results of a similar exercise carried out at a small catchment scale. More recently, Harmon and Doe (2001) provided details of a range of models, physically-based and empirical, which can be used over various spatial and temporal scales to assess the short- and long-term effects of different land management strategies. These publications, however, describe erosion models more from a research than a user perspective. Although they are a source of useful information, they do little to help potential model users to answer the questions raised earlier, or to guide them in the selection of the most appropriate model for a specific application, taking account of the objectives, the environmental conditions and the availability of data. Also, since their publication, there has been an increasing use of geographical information system (GIS) techniques in analysing data for planning and decision-making, and erosion models have been increasingly integrated into geospatial systems, particularly at large catchment and regional scales.

|

EUROSEM

|

Morgan et al. (1998) http://www.es.lancs.ac.uk/people/johnq/EUROSEM.html

|

Chapter 5

|

|

GUEST

|

Misra and Rose (1996)

|

Chapter 11

|

|

LISEM

|

Jetten and de Roo (2001) http://www.itc.nl/lisei

|

Chapter 12

|

|

Modified MMF

|

Morgan and Duzant (2008)

|

Chapter 13

|

|

RUSLE

|

Renard et al. (1997) http://fargo.nserl.purdue.edu/rusle2_dataweb/RUSLE2Jndex.htm

|

Chapter 8

|

|

SHETRAN

|

Ewen et al. (2000) http://www.ceg.ncl.ac.uk/shetran

|

Chapter 14

|

|

SIBERIA

|

Willgoose et al. (1991) http://www.telluricresearch.com/siberia_8.30_manual.pdf

|

Chapter 18

|

|

WEPP

|

Flanagan and Nearing (1995) http://topsoil.nserl.purdue.edu/nserlweb/weppmain/wepp.html

|

Chapters 9, 10, 15, 16

|

The Handbook of Erosion Modelling seeks to address these issues and provide the model user with the tools to evaluate different erosion models and select the most appropriate for a specific purpose, compatible with the type of input data that are available. The book is aimed at model users within government, non-governmental organisations, academic institutions and consultancies involved in environmental assessment, planning, policy and research. The intention is to give existing and potential model users working in the erosion control industry greater confidence in selecting and using models by providing an insight into what users can expect of models in terms of robustness, accuracy and data requirements, and by raising the questions that users need to ask when selecting a model that is appropriate to the type and scale of their problem. It is important that users understand both the advantages and limitations of erosion models.

The Handbook is arranged in two main parts. The first part introduces the user to some important generic issues associated with erosion models. Chapter 2 sets out the various stages that a user should go through when selecting and applying an erosion model, and shows that these are much the same as erosion scientists adopt when developing their models. There is much common ground between model developers and model users, probably more so than most users are aware of. The next four chapters take key issues and discuss them in detail, along with solutions which model users might adopt. Chapter 3 looks at the question of calibration. This is a controversial topic with opinions ranging from those who consider that it is impossible to calibrate the more complex, physically-based models and those who believe that calibration is essential. This chapter is broadly in favour of calibration, showing how it can improve the quality of predictions both in terms of erosion rates and the spatial distribution of erosion. Chapter 4 raises the issue of uncertainty in model predictions. After discussing why we should worry about uncertainty, various approaches are described which can be used to reduce the level of uncertainty. How successful these are depends on the causes of the uncertainty, and model users need to be encouraged to appreciate and understand these. Uncertainty is taken further in Chapter 5, which shows how one approach is used in practice with reference to the application of one specific erosion model. Chapter 6 reviews the issues posed by scale. Many problems faced by users relate to a single scale, be it field, hillslope, small catchment or large catchment, but others need to be addressed at a range of scales. This chapter looks at the problems involved when moving from one scale to another with the difficulty of modelling interconnectivity between hillslope and river systems. At present there are few solutions to the problems that arise when modelling across a range of scales, but several ideas for further research are presented whereby model development and data collection need to become more fully integrated. Chapter 7 shows the importance of choosing the right model for a specific problem and scale, and the implications of using inappropriate models. A frequent occurrence is the misunderstanding by the user of either the problem being addressed or what specific models are able to achieve. Although a dynamic process-based model is often the best choice, there are many situations in which it will not perform better than a simpler statistical model.

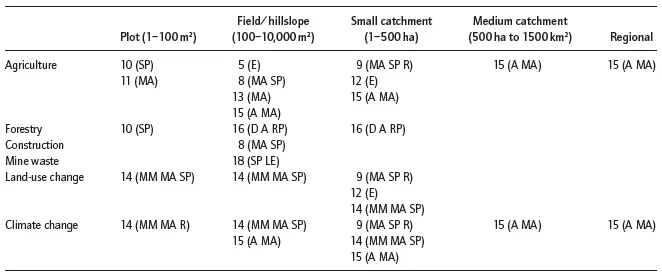

Part 2 of the Handbook looks at specific applications and shows how models are used in practice. Each chapter is really a case study in which a problem commonly faced by environmental planners, consultants and managers is presented. An appropriate model is then chosen and the user is taken through the various steps involved in setting-up and applying the model and interpreting its output. Table 1.2 lists the applications under broad subject headings and for each one identifies the relevant chapter and the spatial scale (erosion plot, field, catchment, region) of the problem being considered. Additional information is provided on the temporal scale, which ranges from individual events to mean annual conditions and long-term landform evolution.

Taking each chapter in turn, Chapter 8 reviews the issues typically faced by field officers of the Natural Resources Conservation Service of the US when predicting erosion from agricultural land and planning soil protection measures. Chapter 9 takes a specific example of a small watershed in southwest Missouri and shows how modelling can assist in designing a strategy for sustainable management under both present land use and climatic change. In Chapter 10, modelling is used to predict rates of soil loss in Brazil from hillslopes on forest roads in Sao Paulo State and from agricultural land under different management systems in Minas Gerais State. Chapter 11 examines how a physically-based erosion model can be used to assess soil erodibility and evaluate different soil conservation practices at four different locations on tropical steeplands, one in China, one in Malaysia and two in Thailand.

The evaluation of sediment yield from a small catchment in a highly erodible area is the focus of Chapter 12, based on a case study on the loess plateau of China. Chapter 13 addresses a problem at a very different scale, namely the transfer of sediment from individual fields to watercourses in southwest England. Chapter 14 returns to the catchment scale, using a model to examine the impacts of land use and climate change on erosion and sediment yield in small river basins where hillslope erosion, river channel and bank erosion and landslides are all important components of sediment production. Chapter 15 is also concerned with assessing the impacts of climate change, but this time over a range of spatial and temporal scales from hillslope to regional and continental. There is no single model that can apply to all situations, and several models are reviewed. Chapter 16 looks at the risk of erosion in forested areas in Montana, US, following disturbance either by timber harvesting or wildfire. Chapter 17 discusses the potential of the Internet as both a source of data and a vehicle for operating erosion models to address problems of environmental management. Chapter 18 examines the role of longer-term landscape evolution models (LEMs) for designing hillslope landscapes to encapsulate and contain mining waste. Chapter 19 reviews the question of modelling gully erosion. Although there is no specific gully erosion model that can be recommended, various approaches that a user can adopt are described.

The Handbook ends with a review of the state-of-art of erosion modelling, as illustrated by the case studies, and discusses the developments that users can expect in the near future. These include the inclusion of more models within geospatial frameworks, associated improvements to modelling across different scales, and the increasing use of web-based approaches and risk-based applications. It is hoped that, by combining a general review of the principles of erosion modelling with examples of model applications across a range of management issues, the Handbook will enable potential users to employ models in a more informed way. Hopefully, managers, decision-makers and policy-makers within the erosion control industry will be encouraged to make more use of models to evaluate present situations, the impacts of control measures and future policies. In addition, model developers may be encouraged to provide better information to model users about the suitability and limitations of their models and what levels of accuracy in prediction they are likely to achieve.

References

Boardman, J. & Davis-Mortlock, D. (1998) Modelling Soil Erosion by Water. NATO ASI Series: Series 1, Global Environmental Change, Vol. 55. SpringerVerlag, Berlin.

De Roo, A.P.J. (1999) Soil erosion modelling at the catchment scale. Catena 37 (3–4).

Ewen, J., Parkin, G. & O’Connell, P.E. (2000) SHETRAN: distributed river basin flow and transport modeling system. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering ASCE 5: 250–258.

Flanagan, D.C. & Nearing, M.A. (1995) USDA Water Erosion Prediction Project: Hillslope Profile and Watershed Model Documentation. USDA-ARS National Soil Erosion Laboratory Report No. 10.

Harman, R.S. & Doe III, W.W. (2001) Landscape Erosion and Evolution Modeling. Kluwer, New York.

Jetten, V. & de Roo, A.P.J. (2001) Spatial analysis of erosion conservation measures with LISEM. In Harmon, R.S. & Doe III, W.W. (eds), Landscape Erosion and Evolution Modeling. Kluwer, New York: 429–45.

Misra, R. & Rose, C.W. (1996) Application and sensitivity analysis of process-based erosion model GUEST. European Journal of Soil Science 47: 593–604.

Morgan, R.P.C. & Duzant, J.H. (2008) Modified MMF (Morgan-Morgan-Finney) model for evaluating effects of crops and vegetation cover on soil erosion. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 33: 90–106.

Morgan, R.P.C., Quinton, J.N., Smith, R.E., et al. (1998) The European Soil Erosion Model (EUROSEM): a dynamic approach for predicting sediment transport from fields and small catchments. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 23: 527–44.

Renard, K.G., Foster, G.R., Weesies, G.A., et al. (1997) Predicting soil erosion by water. A guide to conservation planning with the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE). USDA Agricultural Handbook No. 703.

Willgoose, G., Bras, R.L. & Rodriguez-I turbe, I. (1991) A physically based coupled network growth and hillslope evolution model: 1. Theory. Water Resources Research 27: 1671–84.

![]()

Part 1

Model Development

![]()

2

Model Development: A User’s Perspective

R.P.C. MORGAN

National Soil Resources Institute, Cranfield University, Cranfield, Bedfordshire, UK

2.1 Introduction

The last 40 years or so have witnessed the development of a very large number of erosion models operating at different scales and different levels of complexity, with huge variations in the quantity and type of input data required and, at least according to the model developers, covering a wide range of applications. A potential user of erosion models is therefore faced with a bewildering choice when attempting to select the best model for a particular purpose. All too often, the choice of a model is made more difficult because the user is unable to define the problem precisely enough to state what output is required; for example, whether knowledge of erosion rates is needed as a mean annual value or for a specific year, season, month, day or storm, and if the latter, whether it is a storm total or a value at the storm peak which is wanted. The user is sometimes uncertain whether this information is needed for a field, a particular hillslope or a catchment. Perhaps knowledge of actual erosion rates is not needed at all, and all that is required is an idea of the location of erosion within the landscape or an indication of the time of year that it is most likely to occur. Even when the requirements are clearly defined, the user is still confronted with the difficulty that most models are not accompanied by clear statements of the purposes and conditions for which they were designed, their limitations or indicators of the accuracy of their output.

This chapter discusses how the user might deal with these issues. It does so by proposing that users should adopt the same procedures in analysing their problem as model developers adopt in constructing their models. By understanding how m...