![]()

Part 1

Hematopoiesis

![]()

Chapter 1

Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis

Bijal D. Shah1 and Kenneth S. Zuckerman1,2

1University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA

2H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA

Introduction

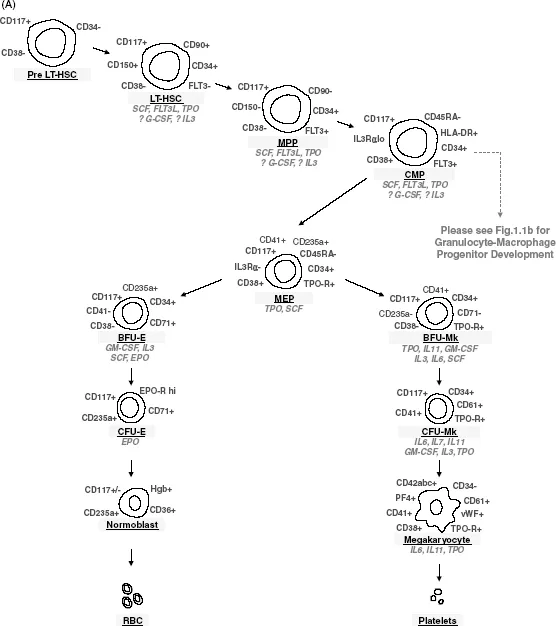

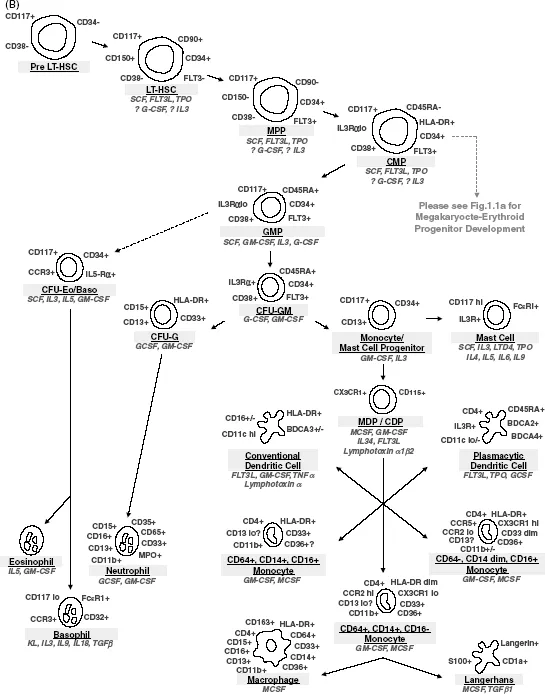

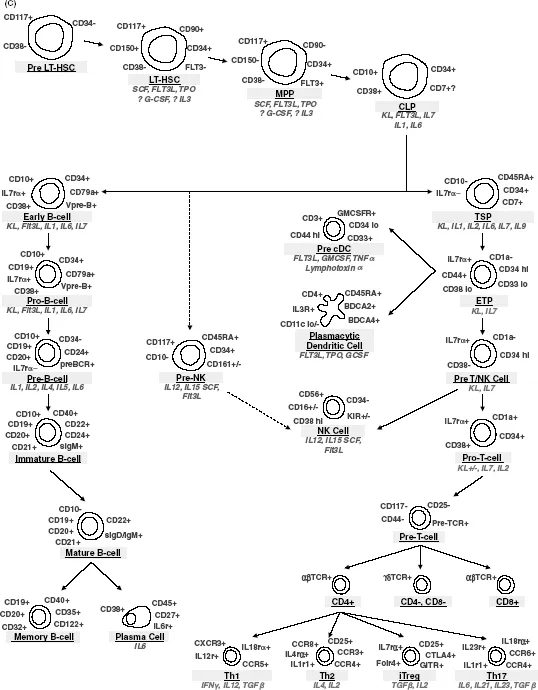

Hematopoiesis, simply stated, describes the regulated process of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal and differentiation into lineage committed progeny. Pluripotent HSC are rare cells (<1 of 10 000 bone marrow cells) specifically characterized by their proliferative capacity (though under steady state conditions >95% of HSC are quiescent, non-dividing cells at any one time), pluripotency (they can regenerate the entire spectrum of mature blood derived cells), and self-renewal. The hierarchy of hematopoietic cell differentiation is depicted in Figure 1.1. HSC reside in close association with hematopoietic stromal cells within specific microenvironmental niches that function in concert with a variety of both multilineage and single lineage-specific hematopoietic growth factors, stromal cells, and extracellular matrix molecules to regulate their survival, cell cycle progression, proliferation, and differentiation. These processes of self-renewal, proliferation, differentiation, and cell death are tightly regulated under normal conditions throughout life. A normal individual maintains steady state numbers of blood cells within a very tight range with no more than a few percent variation from day-to-day, with constant production of the number of new cells required to replace the number of senescent cells that die. On average erythrocytes survive in the circulation for about 120 days, platelets for about 10 days, and neutrophils for about 6–12 hours. In order to replace senescent blood cells, the bone marrow of normal adult humans must produce about 180–250 billion erythrocytes, 60–100 billion neutrophils, and 80–150 billion platelets every day, or about 1016 (10 quadrillion) blood cells in a lifetime, with only minimal reduction in the bone marrow cell production capacity as a result of aging. The bone marrow can respond rapidly, in lineage-specific manner, to increase production of new blood cells by 6- to 8-fold over baseline under conditions of demand for each specific type of blood cells, such as in vivo destruction of erythrocytes, platelets, or neutrophils, infections requiring increased neutrophil production, and hemorrhage requiring increased erythrocyte production. Regulation of lymphocyte numbers is much less clearly understood, although it is known that some types of T and B lymphocytes may survive for many years. An understanding of these normal regulatory components in normal hematopoiesis is essential to unraveling the mechanisms that drive malignancy.

Isolation of Hematopoietic Progenitors

In 1961, Till and McCulloch isolated single cell-derived colonies of myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic cells (CFU-S) from the spleens of lethally irradiated mice 1–2 weeks after rescue by bone marrow transplantation [1]. These colonies were capable of extensive proliferation in vivo, exhibited some potential for self-renewal and, for the first time, conclusively demonstrated the presence of a multipotent hematopoietic progenitor cell. However, the lack of lymphoid colony development, as well as experiments in which 5-fluoruracil killed CFU-S without killing cells capable of replenishing CFU-S suggested that a more primitive “pre-CFU-S” must exist [2].

These data were further refined with the advent of flow cytometry, fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS), in vitro hematopoietic progenitor cell systems, and xenotransplantation models, which revealed that long-term bone marrow repopulating HSCs were distinct from CFU cells, or multipotent progenitors (MPPs), and could be further subdivided into cells with short-term (ST-HSC) and long-term (LT-HSC) hematopoietic stem cell repopulation capacity. Specifically, LT-HSCs are defined by their extensive self-renewal capacity, allowing for full reconstitution of an irradiated host following transplantation of these cells. ST-HSCs, alternatively, have less capacity for self-renewal and instead more avidly differentiate into more committed MPPs. As such, ST-HSCs provide short-term hematopoietic cell reconstitution, but are incapable of permanently rescuing humans or other mammals with an aplastic bone marrow after lethal ionizing radiation.

Although some controversy exists, the most widely accepted model suggests that hematopoietic lineage commitment is both a stochastic and instructive process that occurs at specific branchpoints, manifested at the time of cell division. During cell division, HSCs can either divide asymmetrically (a maintenance event with the production of one identical immature daughter cell and one differentiating daughter cell), symmetrically (an expansion/self-renewal event which serves to generate two identically immature daughter cells (self-renewal)), or terminally differentiate (an extinction event, in which both daughter cells are committed to terminal differentiation). The hierarchy of differentiation from HSC to mature end-stage hematopoietic cells is shown in Figure 1.1. As cells progressively differentiate into functional components of the hematopoietic system, they lose proliferative and multilineage differentiation capacity. Regulation of self-renewal, cell cycling, terminal differentiation, and apoptosis is therefore critically important to maintaining the production of hematopoietic elements over a lifetime. It is now clear that extrinsic and intrinsic systems act in concert to generate a network of events that govern HSC fate.

Cytokine Regulation

Cytokines/growth factors include interleukins, lymphokines, monokines, interferons, chemokines, colony-stimulating factors (CSFs), and other hematopoietic hormones. These secreted factors interact with receptors on both pluripotent stem cells and committed hematopoietic progenitor cells to affect their survival, proliferation, and differentiation. The stages of differentiation from pluripotent HSC to fully mature hematopoietic cells of all lineages and the growth factors that play roles in these differentiation events are shown in Figure 1.1. Kit-ligand (also known as stem cell factor (SCF), and Steel factor (SF)) and Flt3 ligand, which function to drive proliferation by binding to the Kit and Flt3 tyrosine kinase receptors, respectively, on CD34+CD38− progenitors are important regulators of the early stages of hematopoietic differentiation from HSC. SCF, in particular, cooperates with multiple cytokines and cytokine receptors to influence differentiation, as well as upregulating BCL-2, BCL-XL, and perhaps other antiapoptotic molecules to promote target cell survival. These receptors are downregulated during normal differentiation. Colony-stimulating factors, including erythropoietin (EPO), thrombopoietin (TPO), granulocyte-macrophage-CSF (GM-CSF), granulocyte-CSF (G-CSF), and macrophage-CSF (M-CSF; CSF-1), induce the differentiation and function of specific hematopoietic cell lineages. These factors accordingly are named for the lineages that they predominantly stimulate, although several also have effects on multipotent hematopoietic progenitors and perhaps even on pluripotent HSC. Alternatively, TGFβ (tumor growth factor-β), TNFα (tumor necrosis factor-α), and IFNs (interferons) all tend to negatively influence hematopoiesis.

Although cytokine-receptor interactions would appear to generate a level of specificity with regards to transcriptional and genomic regulation and, hence, lineage-specific cell differentiation, the convergence of similar molecular pathways upon genomic targets makes it difficult to delineate this. What can be said, however, is that cytokine receptors appear to fall into specific families based upon their signal transducing subunits (see Table 1.1), and that these signaling subunits rely on three major pathways to ultimately influence transcription. These pathways include the JAK-STAT pathway, the MAPK pathway, and the PI3/AKT pathways, although other pathways involving NF-κB, TGF/SMAD, and protein kinase C pathways also play roles in the regulation of hematopoiesis. Importantly, mutations that affect these pathways are well described in lymphomas, myeloproliferative neoplasms, and leukemias [3–6].

Table 1.1 Cytokine receptor families.

| Homodimerizing receptors | G-CSF-R, EPO-R, TPO-R |

| Heterodimerizing receptors | |

| gp130 receptor family | IL6-Rα, LIF-Rβ, IL11-Rα, Oncostatin M-Rα, CNTF-Rα, CLCF-R |

| βC (Common β receptor) receptor family | GM-CSFRα, IL3-Rα, IL5-Rα |

| IL2-R family (γ chain) receptor family | IL4-Rα, IL7-Rα, IL9-Rα, IL13-Rα, IL15-Rα, IL21-Rα |

| Type II Cytokine receptors (interferon family) | IFNα-R, IFNγ-R1/2, IL10-R1/2 |

| Receptors with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity | Flt3, c-Kit |

Mechanistically, growth factors and cytokines act as ligands for transmembrane receptors that are located on the surface of hematopoietic cells, with differing receptor expression on HSC, multipotent progenitors, single lineage precursors and mature hematopoietic cells of different lineages. Dimerization (or conformational change) of receptors occurs following ligand binding. This receptor dimerization and conformational change leads to autophosphorylation of the intracellular portion of the receptors and recruitment of signaling molecules to docking sites on the activated receptors. This leads, in turn, to recruitment, phosphorylation, and activation of a broad range of cytoplasmic effector signaling molecules, such as STATs, Src-kinases, protein phosphatases, Shc, Grb2, IRS1/2 and PI3K via binding at the conserved SH2 domains and phosphorylation sites on the receptors themselves. For example, phosphorylation of STATs leads to the generation of STAT homo- and hetero-dimers, which are then translocated to the nucleus, where they can bind specific nucleotide sequences in the regulatory regions of specific genes to influence transcription of those genes, which determines the proliferation, survival, differentiation, and function of those cells. Similarly, phosphorylation of Grb2 facilitates the activation of SOS, which in turn, influences transcription via activation of the Ras/Raf/Mek/Erk, and the Rho/Mlk-Mekk/Mek/p38-JNK pathways. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K), either directly or indirectly via RAS or IRS 1 and 2, generates PIP3, which in turn activates PKC, SGK, RAC1/CDC42 and AKT. Activation of AKT is particularly relevant to both normal and malignant hematopoiesis, as it can phosphorylate multiple transcription factors, leading to activation of mTOR, MDM2, and NFκB and inhibition GSK3β, FKHR, and BAD. Notably, multiple related proteins and isoforms of many of the signal transduction molecules exist (including JAK, STAT, Mek, Mlk, Mekk, Erk, p38, JNK, PI3K, PIP3, and AKT), and appear to have different nuclear targets depending on the cell type in which activation occurs [3–5].

Transcriptional Regulation

Transcription factors are proteins that interact with the regulatory region of genes, either alone or in protein complexes, to increase or decrease expression of genes that contain specific sequences of nucleotides in these regulatory regions, which are recognized by the specific transcription factors. Transcriptional networks play a central role in the intrinsic regulation of HSC and lineage-committed progenitor cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. Accordingly, these pathways are commonly perturbed in hematopoietic malignancies. Unfortunately, o...