![]()

1

Barriers and Their Social Meaning

Design as Evolution

Much of life is about overcoming barriers. Every organism, from lowly one-celled animals to human beings, exists by interacting with its environment. This interaction includes moving from one place to another, creating a space for the self, lifting a load, or learning how to use a tool. Our ability to interact with the environment is, to a great degree, determined by our characteristics and abilities, such as height, strength, and intelligence, but also by the degree of resistance and its corollary, the support the environment provides in reaching our goals. The relationships humans have with the environment are much more complex than those of other organisms. We have reasoning abilities and tools that give us more freedom of interaction and a wider range of adaptive responses. Ants, for example, use instinctual foraging behaviors to find food and bring it back to their nests. If an ant encounters an obstacle in its path back to its nest, it may climb over or around it. If an observer drops more obstacles in its path, the ant continues to use the same limited set of behaviors to overcome the barrier. Humans, however, have a much larger range of adaptive behaviors. Faced with a situation similar to that of an ant, a person might remove the obstacle, use a map to find an alternative route, or find another source of food. People also can psychologically adapt to the presence of a barrier. A good example is the prisoner who overcomes physical confinement by exploring an interior intellectual world.

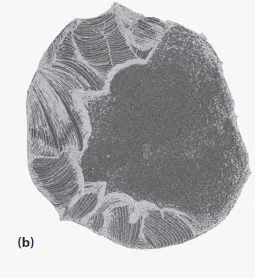

Human social groups have developed sophisticated methods of adaptation to overcome the resistance of environments. Design is an active, purposeful adaptation method that people use to adjust their world to their needs. Through design, humans both remove barriers and develop supportive environments, products, and systems to facilitate achievement of their goals. Design interventions have evolved with human experience and the development of technology. For example, one of the first tools early humans learned to use was a sharp-edged rock. Over time, some people discovered that such a rock could be enhanced by fashioning a sharper edge. Later humans discovered that fashioning a handle on part of the rock increased the comfort of using such a tool. To hunt larger game that would provide more food to support a growing community, others discovered that adding a long handle to the rock added leverage and reduced effort. This was the first prototype of the modern ax (Williams 1981). Figure 1–1 shows this evolution.

Technology can be a barrier as well as a facilitator for usability. For example, the flat-bottomed skiff is a traditional boat design that is ideally suited for use by shell fishers in shallow tidal water. The invention of the outboard engine offered opportunities for fishermen to be more productive, but mounting outboard engines on flat-bottomed skiffs made them unstable (Williams 1981). A new type of boat needed to be designed to overcome this problem. The Boston Whaler is an example of a modern design that works well in shallow water with an engine.

Adaptation is not always successful from an individual and/or community perspective. It can put an individual at risk, lead to maladaptive behavior, or put other people at risk. For example, if residents of a neighborhood adapt to violence by isolating themselves in their homes, afraid to go out in public, both the residents’ quality of life and the health of the community suffer. Design interventions can also lead to negative consequences. Large residential institutions, such as poor houses, mental hospitals, and penitentiaries, were a late nineteenth-century adaptation to urbanization and the resulting increase in crime, poverty, and disability concentrated in cities. But these facilities created enormous barriers to independence and mental health, stigmatized their residents, and corrupted their caretakers (Foucault 1973; Rothman 1971; Sommer 1969). As knowledge about these problems developed in Europe and North America, most of these institutions were dismantled, and new policies of community living and short-term treatment emerged.

Within the context of human evolution, the purpose of design is to help the species increase its survival potential. Design is more than aesthetics, which is primarily a surface effect. Its fundamental purpose is to change the form and organization of our material world and even change how we interact with it. For example, changing the size of schools or developing a gestural language to control computers are both design decisions, even more important than the decision about what color, material, or shape to make the building or computer enclosure. Design is a “soft” tool that extends the effectiveness of human adaptive behaviors.

An environment can provide different degrees of support. Often people are satisfied with lower levels of performance than what could be achieved. Sometimes they accept barriers for some people but not for others. They may even intentionally create barriers to separate certain people from the larger community or one group from another, as in the case of the residential institution. Other goals, such as aesthetics or cost, sometimes may take precedence over the degree of enablement a built environment, product, or system provides.

Universal design, at its most elemental level, seeks to make our built environment, products, and systems as enabling as possible; in other words, it seeks both to avoid creating barriers in the first place and, through intelligent use of resources, to provide as much facilitation as possible to reach human goals. Social and technological trends have converged to put more value on enabling design. We discuss the underlying reasons for these trends in Chapter 3.

Barriers as a Universal Experience

Because the elimination of barriers is so central to the universal design philosophy, it is important to begin this book with an examination of barriers as an experiential and intellectual phenomenon. Doing this will help the reader to understand the potential scope of universal design and the reasons why it is so important in contemporary design thinking.

Any obstacle we encounter can be a barrier to reaching our goals. Barriers may not be complete obstacles but simply resistance of some sort. For example, although a narrow doorway may not entirely prohibit a crowd of people from exiting, it could increase the total time it takes to exit. In an emergency, this can be fatal for some occupants. Other types of barriers are less severe; nevertheless, if many, many minor barriers are encountered in a relatively short period of time, they can be annoying, deter people from reaching goals, and result in the behavioral adaptation of avoidance. For example, driving a car in a congested area for a business appointment may result in many small inconveniences that add up to missing the appointment. A few experiences like that in the same area could result in a decision to seek opportunities elsewhere.

In everything we do, there are barriers: barriers to movement, barriers to space and time, barriers to access, barriers to communication, to perception, or to expression. Although blockades such as walls or locked gates that totally preclude access are obvious, other barriers are not always that easy to perceive. Less obvious examples are steep slopes and inclines, channeling that forces choices and limits spontaneity, discontinuity in flows, distances separating people or things, shortages of space that require people to take turns, noisy places that limit conversation, and cultural markers with little physical substance but high prohibitions on entry. In the world of products, we encounter such barriers as complex operating procedures, excessive forces of operation, ill-fitting equipment and furniture, and things that make us look awkward and out of place in the eyes of others.

A barrier does not always totally exclude use. It can make use difficult, or it can also be a selective barrier that allows use by one group of people and not another or that regulates access by schedule. Moreover, a barrier may be supportive in one sense and restrictive in another. Crime scene tape is an interesting example. It is a very flimsy barrier but one that is very powerful because of its cultural significance and legal implications that force people to avoid an area without significant physical means. Some law enforcement authorities can pass through the marked-off scene while others can enter only with permission. Cubicle farms are another, less obvious type of barrier. They support increased communication among workers on one hand because there are no full-height walls or doors, but they limit our ability to communicate our unique personality, thus creating fodder for a genre of humor about cubicle culture.

If we reflect about encounters with barriers as a general class of experiences faced in daily life, we can conclude that they all impede or restrict the flow of action, information, and communication. Barriers are significant to us in many ways. They can block us out, slow us down, divert us from our goals, cause fatigue, limit our opportunities, or restrict our ability to express ourselves. Barriers can even be used to control people to make them follow a predetermined course of action determined by others, reducing their ability to make choices. Consider, for example, a voicemail menu system or a security checkpoint that forces us to complete a series of meaningless or even degrading tasks to obtain services or benefits.

Barriers in Intellectual Life

While we normally think about barriers as part of our everyday life, they play an important role in our intellectual life as well. The sculptures of Richard Serra are some of the most powerful examples of barriers in art. He constructs huge planes of steel to divide space. When experiencing these sculptures in person, the walls of crude steel are overwhelming. They heighten our perception of barriers and demonstrate the power to separate and divide. Serra’s Tilted Arc was originally installed as a site-specific work in Federal Plaza, New York City (Figure 1–2).

The office workers who regularly used the space complained that the work ruined the plaza, cut off views, created an obstacle to pedestrians, and was a hiding place for criminals. After a long, protracted legal battle, eventually Tilted Arc was removed, even though the public had paid for it through a percent-for-the-arts program (Senie 2002). The reaction that this sculpture provoked illustrates the power that barriers have to affect our lives and the anger that people can feel when restrictions are imposed on them. Even though Serra’s work was critically acclaimed, the regular users of the space experienced its direct impact, which overshadowed any value it had to them as art. New Yorkers put a high value on accessibility to public places. It is possible that Tilted Arc would not have provoked such a reaction in other locations. The story of Tilted Arc demonstrates the interpretive component of barriers. One person’s art can be another person’s symbol of government interference in his or her life.

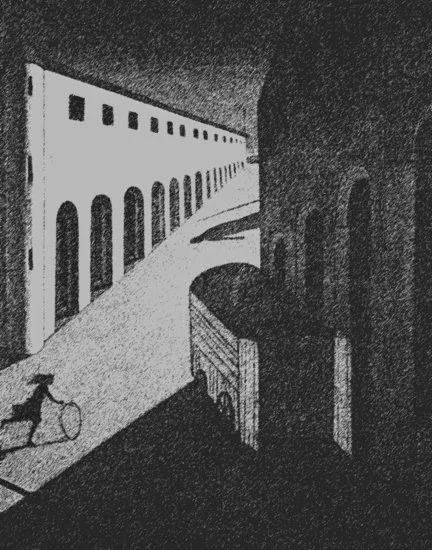

By its very nature, two-dimensional art creates barriers to perception. That is the source of its power. A two-dimensional image cannot be explored; the artist presents only one perspective to us, and it communicates only a specific intent. The frame of a painting and the bounded edge of a photograph limit the viewer’s access to information. We cannot see what is happening outside the frame. Moreover, the static image prevents us from seeing, exploring, and knowing what is beyond the forms within the frame of the art piece. A good example is Melancholy and Mystery of a Street by Giorgio de Chirico (Figure 1–3). In this painting, the shadow on the ground is a strong clue to the presence of something outside the frame, something quite foreboding. So much detail is left out of the representation of buildings and space that the painting creates the feeling of the city as an enigma, an unknown place where potentially dangerous events may occur. The fragile image of the child projects a sense of vulnerability that we often feel in some urban streetscapes.

Physical restrictions are often used as metaphors in literature. One of the most interesting examples is the metaphor of overcoming resistance as a transformation in understanding. In the novel Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson, a relentless snowstorm serves as a metaphor for the gradual shift in the perception of history and fact surrounding a murder trial. As the snowstorm advances, the world of the island on which the story takes place presents more and more resistance to the activities of daily life. The chief protagonist, Ishmael (...