![]()

Part I

Guiding Principles

![]()

Chapter 1

Pride

Observing New China’s 60th anniversary in 2009, Westerners marveled at the country’s momentous changes. The obvious improvement in the standard of living of most Chinese, and the economic strength of the country, is evidenced in virtually every city and town. The diversity in dress and entertainment, the new flexibility in sexual behaviors—even the increase in divorce and legions of lawyers—all speak to the uncontestable fact that China is no longer the drab, monolithic society so ingrained in Western consciousness.

But even more fundamental is the change in outlook and spirit. One need only speak with Chinese people in the major cities to sense their newfound self-confidence and enthusiasm. They tell you plainly what they think—whether how to make money, or their dislike of government bureaucracy, or of the omnipresent air pollution. They give you their opinions bluntly—you don’t have to ask twice—and they don’t look over their shoulder before they speak out.

The change in the economic lives of the Chinese people has been staggering: Since 1978, China’s GDP per capita has increased more than 40 fold. Arguably, the Chinese economy is now the second largest in the world,1 and in another 30 years it may well be the largest. Average salaries are low by Western standards, but prices are also low, so that most people, even rural farmers, are living far better than the income statistics indicate. Over a billion people have access to television; three decades ago only 10 million did. In 1978 there were 200 foreign companies doing business in China; today there are hundreds of thousands. In fact, China absorbs more foreign investment than any country in the world except the United States. Chinese corporations are selling internet routers and refrigerators competitively around the world and Chinese entrepreneurs are building strong private businesses on the Internet. The old communist ideal of the glorious masses in class struggle is dead and buried. It has been replaced by something new and dynamic, an economic engine fueled by personal dreams and national pride.

Although economic improvement—higher standard of living, financial success, luxuries of life—are goals in every country, there is extra energy to achieve these goals in China. The motivation goes beyond material benefits: the Chinese want to show the world that they are in every way a modern nation and in every sense a great power. If this demonstration requires material wealth, technological prowess, military strength, a world-class aerospace program, then these are what they must and will achieve. In every sphere of human endeavor, from business to culture, Olympic athletes to space taikonauts, music and art to modern science and ancient philosophy, China seeks its fair share of world leaders. For example, in every industry of importance, China’s leaders expect its corporations to become among the largest and most successful in the world. When Zhang Ruimin, CEO of household electronics giant Haier, stated in the middle 1990s that Haier’s goal was to become a leading global company, foreign analysts yawned or smirked. Today, Haier is the world’s second largest manufacturer of refrigerators (after Whirlpool), among the top 1000 manufacturers in the world, and its brand name has joined the prestigious list of the World’s 100 Most Recognizable Brands. China is proud that the stock market capitalizations of its companies in energy, telecommunications and banking are among the largest in the world.

The roots of this pride go deep, to the visceral feelings of a people whose civilization of culture and technology led the world for centuries, only to be humiliated and oppressed by foreign invaders and then stymied and scourged by domestic tyrants.

“To understand our dedication to revitalize the country, one has to appreciate the pride that Chinese people take in our glorious ancient civilization,” says China Vice President Xi Jinping. “This is the historical driving force inspiring people today to build the nation. The Chinese people made great contributions to world civilization and enjoyed long-term prosperity,” he explains. “Then we suffered over a century of national weakness, oppression and humiliation. So we have a deep self-motivation to build our country. Our commitment and determination is rooted in our historic and national pride.”2

Xi is at pains to stress that pride in China’s recent achievements should not engender complacency: “Compared with our long history, our speed of development is not so impressive, because it took thousands of years for us to reach where we are now. We need to assess ourselves objectively,” he emphasizes. “But no matter what, China’s development, at least in part, is driven by patriotism and pride.”

Li Yuanchao, head of the Party Organization Department, which is responsible for all high-level personnel appointments in the Party, government and large state-owned enterprises, emphasizes that it’s China’s national spirit that has motivated people to keep looking ahead and seeking further progress.

“Although the Chinese people are not as wealthy as Westerners, and China lags behind developed countries in many areas such as technology, social systems, and environmental protection,” Li says, “I am confident that the Chinese people as a whole are very positive about their country’s development and have confidence in their future. We have a sense of adventure and pride and we are ambitious to build our society.”3

My first lesson in how deep such pride runs came in 1992. I had arrived in China for the first time three years earlier, in February of 1989, about six weeks before students began gathering in Tiananmen Square, but it would be years before I would begin to understand what was really going on here. After the tragic events of June 4, I determined not to return to China. About 15 months later, however, my mind was changed by appeals for support from reform-minded friends. When I did come back, I came to know Professor Bi Dachuan, an academic (mathematician) and defense analyst with quick wit and trenchant criticism. It was a time of repressed freedoms: the post-Tiananmen conservatism was in its ascendancy; if anyone in Beijing wanted to talk politics—when confiding to foreign friends, for example—they would insist on leaving their offices or homes and walk around in the open air or drive around in moving cars.

That’s what made Bi stand out. Even then, he remained cavalier in his criticism of the government, the planned economy, classical communism. His comments were slyly comical, delivered with a mischievous glint of impolitic cynicism. Bi was certainly not alone among the Chinese intelligentsia in disparaging the government, but I was nonplussed when he offered these barbed witticisms in much-too-public situations, such as when addressing a dozen of his professional colleagues. How could he get away with such an unbridled tongue, I wondered?

Although I didn’t at the time know him well, I couldn’t recall Bi having said anything complimentary about China’s political or economic system—and so, one fine day on a remote hilltop outside Beijing, I felt secure in applauding the American action in preventing the 2000 Olympics from being held in Beijing. This was how the U.S. government intended to punish the Chinese government for its armed response in Tiananmen Square. Bi and I were alone, and I was fully expecting his hearty support of America’s blackball.

His response left me speechless.

“You stupid Americans,” he scolded me sharply. “You insult China and you offend me!” He continued, unsmiling. “How stupid and insulting,” he said again, glaring at me as though I myself had cast the blackballing vote. “How stupid of your country and how insulting to mine!”

It was a verbal stinging I shall not forget, and a searing tutorial of what really counts in China. Don’t allow the internal disputes to cloud your vision. Don’t assume that derogations of the government, or of communist ideology, indicate a diminished patriotism. The pride of the Chinese people—pride in their country, heritage, history; pride in their economic power, personal freedoms, and international importance; and, yes, pride in their growing military strength—is a fundamental characteristic that one encounters over and over and over again. As I see it, Pride is the first of the guiding principles that energizes a great deal of what is happening in China today.

Chinese pride invites itself into diverse policy debates. Rarely does it determine decisions, but often it influences them. “It involves the pride of the nation,” is how former Information Minister Zhao Qizheng characterizes Chinese advances in science and technology. Consider China’s spaceflight programs, including the Shenzhou manned spacecraft and lunar missions, an apparent luxury in a country still grappling with widespread poverty, but enthusiastically supported by an overwhelming majority of the people. Why? Pride.

Although President Hu Jintao stresses how science and technology drives China’s development, he also radiates pride in China’s renewed contributions to humanity. Speaking just after the successful return of China’s first manned space voyage, Shenzhou V, in 2003, Hu said, “Our science-based civilization is due to the efforts of all nations and is a sterling demonstration of human creativity . . . spurred by the interaction and integration of the world’s diverse wisdom and cultures.” Hu asserted that, over time, each great civilization has contributed to the global advancement of science and technology, and that history shows that the active, free-flowing exchange of information among civilizations promotes such advancement.4 Hu attends ceremonies for each of China’s manned space flights.

Zhao Qizheng also points with pride to the fact that, during World War II, China was the only country in the world that gave shelter for Jews seeking to escape the Nazi Holocaust in Europe. While even America and Britain refused entry for Jewish refugees, China, though enduring severe tribulation at the hands of the Japanese, opened its doors so that more than 20,000 Jews could come to safety in Shanghai, where they became known to history as the “Shanghai Jews.”

Moreover, consider the long-standing internal debate over whether China should enter the World Trade Organization (WTO). Although the contesting views pitted the economic benefits of foreign investment against the heightened competitive pressure from foreign companies, an underlying motivation was that China belongs in the WTO because China is a great nation and must be counted as such.

This quest for pride is woven into the fabric of much of China’s modern history. In the West, for example, the Korean War is remembered as a wretched, miserable conflict, which epitomized the bleak years of the Cold War. For many in China, however, the same conflict is viewed as a crucible of national resuscitation and revival. After three years of hurling wave after wave of human sacrifices, China managed to end the war in a stalemate. It was an exceptional achievement. The United States, the greatest military power in the world, which less than ten years earlier had vanquished both Germany and Japan, was battled to a draw – grit and determination, in the Chinese view, having thwarted far superior military technology.

Though “victory” came at a tremendous cost—700,000 to one million Chinese lives were lost,5 including that of Mao Zedong’s own son—for many Chinese citizens, the war seemed a turning point. The war was all about national sovereignty and national pride. The treaty ending the Korean War was the first in over a century which was not “unequal.” Chinese credited the Communists, particularly Mao, with the country’s reemergence as a world power. After interminable years of subjugation and humiliation, China finally had a unified and independent government, not beholden to foreigners. Though Sino-American relations had hit an all-time low, China had stood up with pride.

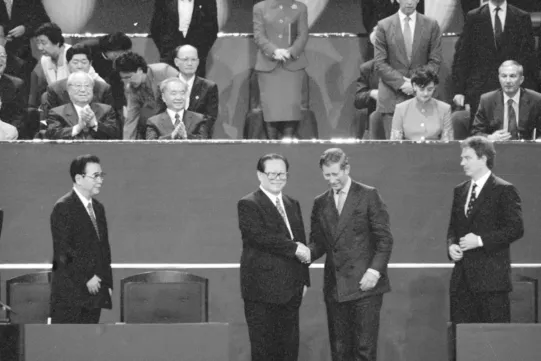

Such pride was in evidence again 45 years later, as China celebrated the end of British rule in Hong Kong, and its return to Chinese sovereignty. For 925 days before July 1, 1997, a huge “countdown board” in Tiananmen Square ticked off the seconds to the historic event. As the Chinese flag reached the top of the flagpole eight seconds after midnight, the precise time determined in painstaking negotiations, joyous pandemonium broke out across China as huge crowds screamed, jumped and danced, waving Chinese and Hong Kong flags. Colonial humiliation of 155 years had come to an end.

In 2006, Hong Kong’s stock market surpassed New York as the world’s second most active board (after London) to float initial public offerings. The largest new stock listings were companies from China.

If the stock exchange in Hong Kong, with its legions of investment bankers wearing elegant tailored suits, seem from a different planet than the killing fields of Korea, with its legions of exhausted soldiers wearing filthy military fatigues, they draw together under the rubric of Chinese pride.

Sovereignty exemplifies Chinese pride. Even the Soviet Union, China’s fraternal-socialist-communist big b...