- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Adult Congenital Heart Disease

About this book

- Guides practicing physicians in the practical aspects of how to diagnose and treat patients with congenital heart disease

- Reviews the most common congenital cardiac anomalies seen in practice

- Focuses on both clinical evaluation and diagnostic imaging modalities as well as practical management issues, as well as when to refer patients to tertiary care centres

- Each chapter is preceded by a case study to exemplify the issues which may be challenging in practical management

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adult Congenital Heart Disease by Carole A. Warnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Cardiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Secundum atrial septal defect

A 20-year-old woman presented for evaluation of palpitations and one episode of near syncope after exertion. Her past medical history was remarkable only for a diagnosis of exercise-induced asthma. She was involved in competitive sports at her University, participating on the track team. She denied any chest discomfort, dyspnea at rest, or perceived exercise limitation. She had never had lower extremity edema, orthopnea, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. There was no history of cardiac or pulmonary disease in her family. Physical exam revealed a normal jugular venous pressure. The carotid upstroke was normal. The lungs were clear to auscultation and percussion bilaterally. The cardiac exam was notable for a 1+ right ventricular impulse with a normal left ventricular impulse. The first heart sound (S1) was normal, but the second heart sound (S2) was persistently split, with no variation with respiration. The pulmonary component of S2 was mildly accentuated. A systolic crescendo–decrescendo murmur, grade I/VI, was heard at the upper left sternal margin. No diastolic murmur or added heart sounds were heard. There was no evidence of cyanosis, clubbing, or edema of the extremities.

Evaluation included a chest x-ray (Fig. 1.1) that demonstrated increased pulmonary vascular markings, enlarged central pulmonary arteries, and cardiac enlargement involving the right heart chambers. An electrocardiogram revealed normal sinus rhythm with right axis deviation and right bundle branch block. The P-R interval was normal. Two-dimensional (2-D) echocardiogram was notable for moderate–severe right heart enlargement, mild tricuspid valve regurgitation, and a secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) measuring 22 mm. The estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 40 mm Hg. The pulmonary valve was normal. A Holter monitor revealed no atrial or ventricular arrhythmias.

Fig. 1.1 Chest x-ray demonstrating enlarged cardiac silhouette, enlarged central pulmonary arteries, and increased pulmonary vascularity.

Embryology and anatomy

Atrial septation is a complex embryological event that occurs in the first 60 days after conception. Throughout the septation process, a channel for blood flow must be maintained between the left and right atria so that placental blood (oxygenated) that is entering the right atrium can be shunted to the left atrium and into the systemic circulation. As endocardial cushion tissue closes the ostium primum, the ostium secundum forms via fenestrations in the anterosuperior position of the septum primum. The septum secundum then develops and eventually provides partial closure of the ostium secundum. At the completion of atrial septation, the limbus of the fossa ovalis is the septum secundum and the septum primum is the valve of the fossa ovalis. Secundum ASDs occur when there is inadequate septum primum. The underlying cause of this malformation is usually multifactorial, although there are a few recognized genetic defects that result in secundum ASD, such as Holt-Oram syndrome.

Pathophysiology

A secundum ASD allows blood to cross the atrial septum. The amount of shunt is determined by the end-diastolic pressures of the ventricles, the size of the defect, and the status of the atrioventricular valves. Usually, the right ventricular end-diastolic pressure is lower than the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, creating a left-to-right shunt. Right-to-left shunting can occur when there is significant tricuspid valve disease or when the right ventricular end-diastolic pressure is elevated by pulmonary valve disease, abnormal compliance of the right ventricle, or pulmonary hypertension.

A left-to-right shunt at the atrial level results in volume overload of the right atrium and right ventricle. Volume overload leads to dilatation of these chambers, which can eventually result in right ventricular systolic dysfunction. Tricuspid valve regurgitation can also progress as a result of right ventricular enlargement and subsequent annular dilatation. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure is proportional to the pulmonary vascular resistance multiplied by the pulmonary arterial flow (PAP ≈ PVR × Qp). Therefore, mildly elevated pulmonary artery pressures are not unexpected, even when the pulmonary vascular resistance is normal, since the pulmonary arterial blood flow is increased secondary to the left-to-right shunt. However, increased blood flow through the pulmonary arteries increases shear stress on the arterial wall and can lead to changes in the pulmonary vasculature that result in increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension. In the setting of severe pulmonary hypertension, a right-to-left shunt at the atrial level results in systemic desaturation that is unresponsive to supplemental oxygen. This right-to-left shunt in the setting of pulmonary vascular disease is called Eisenmenger Complex and occurs in approximately 5% of secundum ASDs, most commonly in women. Left atrial enlargement will occur, but left ventricular enlargement is unusual given the compliance characteristics of the left ventricular myocardium.

Natural history

The presentation of secundum ASD depends on the size of the shunt and the associated cardiac status. Defects associated with very large shunts may present in infancy with failure to thrive, but it is not uncommon for large defects to be diagnosed for the first time in adulthood. Left ventricular compliance tends to diminish with age, often in association with the onset of hypertension or coronary artery disease. The stiffer left ventricle then increases the left-to-right shunt through the ASD, causing progressive right ventricular and right atrial enlargement. Often patients present for the first time in their 40s and 50s with atrial fibrillation. Other symptoms include exercise intolerance, frequent upper respiratory tract infection, and palpitations.

Diagnosis

The physical exam may demonstrate a pronounced right ventricular impulse, but the left ventricular impulse is usually normal. The second heart sound (S2) may be widely split, with no variation with respiration. The pulmonary component of the second heart sound (P2) is variably accentuated, depending on the pulmonary artery pressures. A systolic murmur from increased flow through the pulmonary valve is heard at the upper left sternal margin. If the left-to-right shunt is significant (Qp:Qs >2.5:1), a diastolic murmur representing increased flow across the tricuspid valve can be heard.

The chest x-ray findings of secundum ASD include cardiomegaly related to right-sided cardiac enlargement, central pulmonary artery enlargement, and prominent pulmonary vascularity secondary to pulmonary overcirculation.

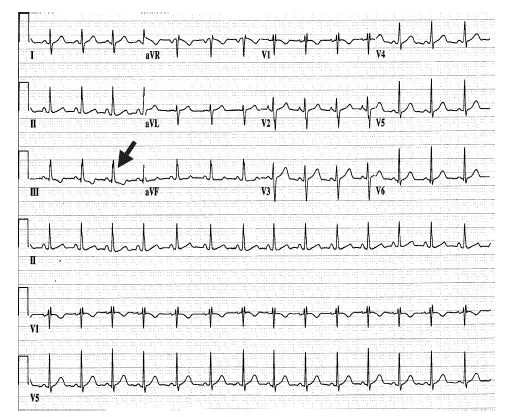

The electrocardiogram will usually demonstrate a right bundle branch block with right axis deviation. Crochetage (Fig. 1.2), a notch seen in the QRS in lead II and III, has also been reported in secundum ASD [1].

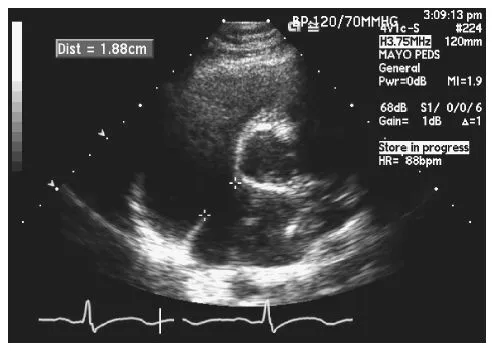

Transthoracic echocardiography is invaluable in the diagnosis of secundum ASD. Even if the defect itself cannot be visualized, the hemodynamic consequence of the shunt can be assessed by an evaluation of the right heart size and function. Identification of the defect by surface echocardiogram is influenced by the size of the defect. The subcostal window provides a good look at the atrial septum and should be used. The parasternal short axis view at the base of the heart may also demonstrate the defect (Fig. 1.3). The apical four-chamber view can be misleading; when the atrial septum is parallel to the echocardiographic signal, drop out may occur. Tilting the apical view off-axis will align the atrial septum at an angle and allow for better 2-D and color interrogation. The degree of tricuspid valve regurgitation should be assessed, as this may influence the mode of repair. The pulmonary artery pressures should be estimated via the modified Bernoulli equation (ΔP = 4v2), with the systolic pressure calculated from the tricuspid valve regurgitation velocity (assuming there is no pulmonary stenosis) and the diastolic pressure estimated from the pulmonary regurgitation end-diastolic velocity. There is very little usefulness in calculating the ratio of pulmonary blood flow to systemic blood flow (Qp:Qs) by echocardiography, as the measurements are often inaccurate.

Fig. 1.2 Crochetage. Note the notch at the peak of the QRS complex in leads II, III, and aVF.

Fig. 1.3 Transthoracic echocardiogram, parasternal short axis view. The atrial septal defect measures 1.88 cm.

Transesophageal echocardiography allows improved visualization of the atrial septum and therefore enhanced diagnostic accuracy. Transesophageal echocardiography should be employed if the diagnosis is in question or if there is a concern about the adequacy of the residual atrial septal tissue when device closure is being considered. Transesophageal echocardiography also allows improved visualization of the pulmonary venous return and can be used to rule out anomalous pulmonary venous connection, which is an important differential diagnosis if a patient is found to have right ventricular enlargement and no ASD.

Cardiac catheterization providesaccurate pressure measurements. Flow measurements can be obtained through various methods. These measurements can then be used to calculate pulmonary vascular resistance and quantitate the shunt volume. However, in the modern era, cardiac catheterization is unnecessary unless coronary angiography is being performed or the patient has important pulmonary hypertension. Cardiac catheterization should be employed when there is a question regarding pulmonary artery pressure and vascular resistance before committing to defect closure. Currently, the main role for cardiac catheterization in the patient with isolated secundum ASD is therapeutic.

A secundum ASD that is associated with right ventricular volume loading should be considered for closure. The demonstration of a Qp:Qs greater than 1.5:1 is not required. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect ASDs and can provide right ventricular volume measurements, as well as an evaluation of the pulmonary venous return [2,3].Shunt calculations can be also be determined [4].MRI is not a first-line test in the evaluation of secundum ASD because of cost, time, and availability constraints, but it should be considered as an excellent alternative in patients who cannot undergo transesophageal imaging.

Treatment

Hemodynamically significant ASDs (those that have resulted in right heart enlargement) should be closed to prevent the complications of right heart failure, atrial dysrhythmia, and pulmonary hypertension. Closure of important secundum ASDs before the age of 25 years results in an excellent long-term prognosis. Closure after the age of 40 years reduces the complications related to right heart failure, but the increased risk of atrial dysrhythmia remains [5].

Closure of a secundum ASD can be accomplished surgically or percutaneously. Surgical closure has been performed successfully since 1953 [6]. The surgical approach is via midline sternotomy or right thoracotomy. Minimally invasive technique through a right thoracotomy is currently being used in some centers. At the time of surgery, the ASD can be suture closed or patched, depending on the size. Patch closure may involve autologous material, bovine pericardium, or artificial material. The mortality for surgical closure of ASD is reported as 0.3% in the STS database [7] for procedures performed between 1998 and 2002. Complications include incomplete closure, obliteration of the inferior caval orifice, heart block, and atrial arrhythmias.

Percutaneous closure can now be accomplished. There are several devices available for use. Percutaneous closure can be considered for defects up to 38 mm in stretched diameter, but closure becomes more difficult for defects greater than 30 mm. Adequate septal tissue rims must be present to anchor the device, but patients with deficient retro-aortic rims have undergone successful percutaneous closure. The success rate of percutaneous closure is greater than 90%, with a complication rate of about 7%. Reduction in right ventricular size is seen in the majority of patients. Complications include atrial fibrillation, cardiac perforation, device migration, and access site complications [8]. Infection and thrombosis of the device have been reported after successful closure.

The mechanism of closure should be determined based on anatomic characteristics and patient preference. Patients with other cardiac anomalies that need treatment, including anomalous pulmonary venous return, should undergo surgical repair. Patients with more than moderate tricuspid valve regurgitation may need to be considered for combined surgical ASD closure and tricuspid valve repair. Patients with a history of atrial fibrillation may benefit from a surgical MAZE procedure, although catheter-based arrhythmia management can be considered in conjunction with device closure. Any catheter-based arrhythmia procedure must be performed prior to device closure, as access to the left atrium will be difficult after device implantation.

Patient follow-up

The patient elected to proceed with percutaneous closure of the defect. The closure was successful without residual shunt. On a follow-up visit, 1 year after the procedure, the patient was asymptomatic and had improved her 200-meter race times dramatically. Echocardiogram was notable for normal right ventricular size and function, mild tricuspid valve regurgitation, and an estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 28 mm Hg.

References

1. Heller J, Hagege AA, Besse B, et al. “Crochetage” (notch) on R wave in inferior limb leads: a new independent electrocardiographic sign of atrial septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:877–82.

2. Chin SP, Kiam OT, Rapaee A, et al. Use of non-invasive phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging for estimation of atrial septal defect size and morphology: a comparison with transesophageal echo. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2006;29:230–4.

3. Greil GF, Powell AJ, Gildein HP, Geva T. Gadolinium-enhanced three dimensional magnetic resonance angiography of pulmonary and systemic venous anomalies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:335–41.

4. Beerbaum P, Korperich H, Barth P, et al. Noninvasive quantification of left-to-right shunt in pediatric patients: phase-contrast cine magnetic resonance imaging compared with invasive oximetry. Circulation 2001;103:2476–82.

5. Murphy JG, Gersh BJ, McGoon MD, et al. Long term outcome after surgical repair of isolated atrial septal defect. Follow-up at 27 to 32 years. N Engl J Med 1990;323(24):1645–50.

6. Lewis FJ, Roufle M. Closure of atrial septal defects with aid of hypothermia: experimental a accomplishments and the report of one successful case. Surgery 1953;33:52–9.

7. STS Congenital Heart Surgery Data Summary. Available at: http://www.sts.org.

8. Butera G, Carminati M, Chessa M, et al. Percutaneous versus surgical closure of secundum atrial septal defect: comparison of early results and complications. Am Heart J 2006;151:228–34.

Chapter 2

Atrioventricular septal defects

Case #1

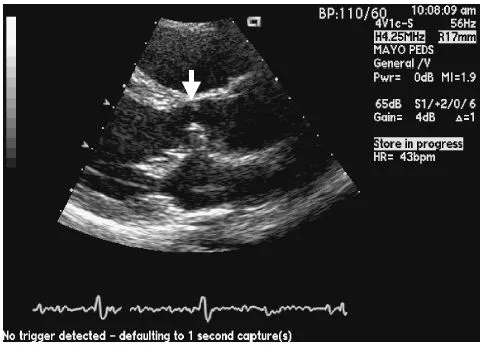

A 17-year-old girl born with partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) had closure of the primum atrial septal defect (ASD) and repair of a cleft in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve when she was 18 months of age. She did well and her growth and development were normal. She participated in high school sports and had no limitations. It was noted several years prior to the current presentation that she had developed a systolic ejection murmur. Echocardiography demonstrated the images shown in Fig. 2.1. That echocardiogram also demonstrated trivial mitral valve regurgitation and mild aortic valve regurgitation.

The echocardiograph in Fig. 2.1 demonstrates tissue in the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) that represents accessory connections from the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve to the septum.

Case #2

A 58-year-old woman originally presented at age 45 years with progressive dyspnea on exertion. She was an aerobics instructor at the time and noticed that her workout routine had become progressively more difficult over the previous 3–4 years. She denied any chest pains, palpitations, or other symptoms. She had never had cardiac rhythm issues. Her work-up 13 years before included a chest x-ray that demonstrated cardiomegaly. This prompted an echocardiogram that showed a large primum ASD and moderate mitral valve regurgitation. At that time, she underwent repair of a primum ASD and closure of a cleft in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve. It was noted immediately postoperatively that there was mild narrowing of the LVOT. A soft systolic ejection murmur was present, and Doppler echocardiography demonstrated a mean gradient of 12 mm Hg across the LVOT. She had mild residual mitral valve regurgitation.

Fig. 2.1 Parasternal long axis projection demonstrating a subaortic membrane (arrow) that developed in a teenager, 15 years after repair of partial AVSD.

Now, at age 58 years, she has not seen a cardiologist for 5 years. Her primary care physician noted a loud systolic ejection murmur during a routine physical exam. This prompted re-evaluation in an adult congenital heart disease clinic. She has two systolic murmurs. The first is a harsh 3/6 ejection murmur best at the mid left sternal border radiating toward the right upper sternal border. There is no ejection click. The second heart sound is physiologically split. The second murmur is a 2/6 harsh holosysto...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface

- Foreword

- Chapter 1: Secundum atrial septal defect

- Chapter 2: Atrioventricular septal defects

- Chapter 3: Pulmonary stenosis/right ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- Chapter 4: Ventricular septal defect

- Chapter 5: Pulmonary arterial hypertension in Eisenmenger Syndrome

- Chapter 6: Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries

- Chapter 7: Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- Chapter 8: Coarctation of the aorta and aortic disease

- Chapter 9: Transposition of the great arteries after a Mustard atrial switch procedure

- Chapter 10: Tetralogy of Fallot

- Chapter 11: Single ventricle physiology

- Chapter 12: Ebstein’s anomaly

- Chapter 13: Imaging in adult congenital heart disease

- Chapter 14: The chest x-ray in congenital heart disease

- Chapter 15: Arrhythmias in congenital heart disease

- Chapter 16: Pregnancy and contraception

- Index

- Author Disclosure Table