![]()

Section 1

![]()

1

Notes on the Immune System

Tracey J. Lamb

Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, USA

This chapter provides some background to the immune system, outlining the cells involved in carrying out immune responses, the receptors mediating recognition of foreign antigens (such as those carried by parasitic organisms) and the effector mechanisms activated to destroy parasites and contain infection. This outline is not a comprehensive account of the workings of the immune system; instead, these notes focus on the aspects of the immune system that are most relevant to the chapters which follow on specific parasite infections.

Readers are encouraged to refer to the suggestions for further reading cited at the end of this chapter, or to one of the many comprehensive textbooks published, such as Janeway's Immunobiology, for a more detailed account of specific aspects of the immune system.

1.1 The immune system

The body has external physical barriers to prevent infection, such as the skin, the production of sweat containing salt, lysozyme and sebum, and the mucous membranes, which are covered in a layer of mucous that pathogens find hard to penetrate. If these barriers are breached, the body will then mount an immune response and mobilise immune cells to destroy the intruder.

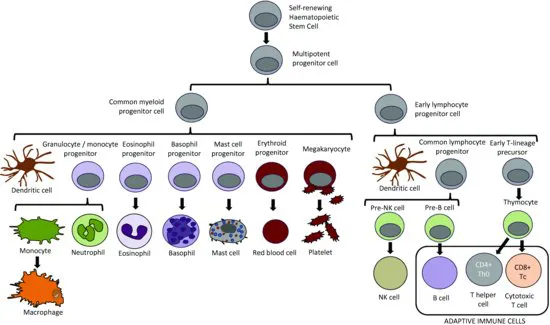

Immune responses are carried out by a variety of different immune cells, all of which initially arise from progenitor stem cells in the bone marrow (Figure 1.1). While most cells mature in the bone marrow, T cells undergo additional development in the thymus. The number of immune cells in the body (homeostasis) is regulated through tight controls on haematopoiesis in the bone marrow, an environment rich in growth factors (such as colony-stimulating factors) and cytokines that support the growth and differentiation of immune cells. The bone marrow and thymus are known as the primary lymphoid organs, because they are the primary sites of immune cell development and maturation.

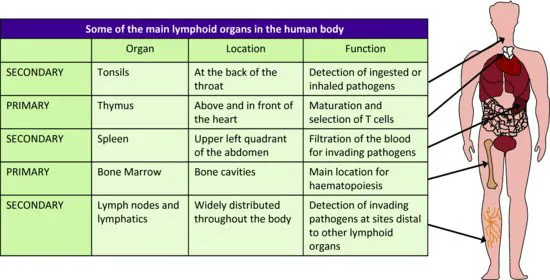

Once mature, immune cells exit the bone marrow (or the thymus, in the case of T cells) and take up residence in highly organised structures composed of both immune and non-immune cells, known as the secondary lymphoid organs (Figure 1.2). Although immune responses are initiated at the point where the body's external barrier has been breached, the establishment of an immune response – particularly the adaptive arm of the immune response – occurs in the secondary lymphoid organs draining the site of infection.

The immune system has evolved a number of effector mechanisms capable of destroying pathogenic organisms. Immune responses can be classified as innate or adaptive (see Table 1.1). The innate arm of the immune system recognises pathogens non-specifically and generates immediate generic mechanisms of pathogen clearance. The adaptive arm of the immune system is more specific for individual pathogens, and it takes a number of days to develop.

There is a high degree of ‘cross-talk’ between the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system. In general, an adequate adaptive immune response is only activated after initiation by the cells of the innate immune system; conversely, innate immune effector mechanisms become more efficient by interaction with an active adaptive immune response.

1.2 Innate immune processes

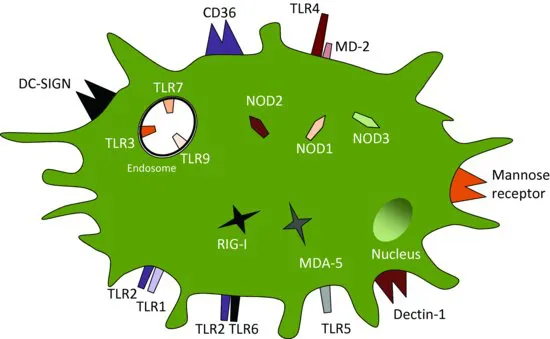

The innate immune system is able to mount an immediate immune response to a foreign pathogen, or to whatever is ‘dangerous’ to the human body as embodied by Matzinger's ‘Danger hypothesis’. Innate immune responses are generic and mounted upon recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) commonly found in molecules that are part of, or produced by, pathogenic organisms. PAMPs are recognised by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs – see Figure 1.3), primarily (but not exclusively) expressed on (and in) phagocytic antigen presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and some types of granulocytes. PRRs can also recognise host molecules containing damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) – molecules that are often released from necrotic cells damaged by invading pathogens.

Table 1.1 Functions of the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system.

| Immune recognition | |

| Immune effector mechanisms |

| Immune regulation |

| Immunological memory |

1.2.1 Inflammation

Once recognition of PAMPs or DAMPs occurs, a series of innate immune processes are activated by innate immune cells that contribute to pathogen destruction. ‘Inflammation’ is a generic term used to describe the dilation and increased permeability of the blood vessels in response to leukotrienes and prostaglandins secreted by phagocytes upon pathogen recognition. Inflammation results in increased blood flow and in the loss of fluid and serum components from capillaries into tissue, as well as the extravasation of white blood cells to the breached area. Superficially, inflammation is responsible for the visible symptoms swelling, pain and redness in infected tissue.

1.2.2 The acute phase response

The acute phase response is initiated by activation of macrophages upon ligation of PRRs with pathogen-associated molecules. This term is used to describe the production of several different proteins which enhance the containment and clearance of invading pathogens.

The production of acute phase cytokines (interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)) are collectively called endogenous pyrogens, because they stimulate the induction of prostaglandin E2, which acts on the hypothalamus to induce fever. Fever is effective in inhibiting the growth of some pathogens and can also enhance the performance of phagocytes. When uncontrolled, however, fever can be damaging to the body.

IL-6 acts on the liver to induce the production of acute phase proteins which include C-reactive protein, serum amyloid protein and mannose binding lectin (MBL). Acute phase proteins opsonise invading pathogens, promoting their phagocytosis and activating the complement pathway to induce pathogen lysis – the latter a particular feature of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) which activates the lectin-pathway of complement (see below).

1.2.3 Anti-microbial peptides

Anti-microbial peptides vary in length from between 12 and 50 amino acids, and are ionically charged molecules (anionically or cationically). In mammals, there are two large families of anti-microbial peptides: defensins and cathelicidins. These peptides can opsonise pathogens, attaching and inserting into the membrane to modify the membrane fluidity and form a pore that lyses and destroys the pathogen. It has also been suggested that some anti-microbial peptides exert their anti-microbial effects by translocating across the pathogen membrane and inhibiting essential enzymes necessary for nucleic acid and protein synthesis, effectively killing the pathogen by starvation. Anti-microbial peptides are effective against some protozoan pathogens as well as against bacteria.

1.3 The complement cascade

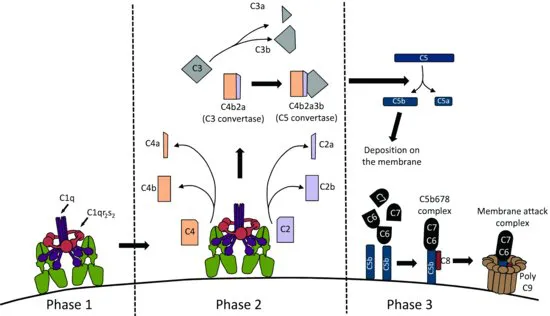

The complement cascade involves several different components activated in sequence leading to the generation of a cytopathic ‘membrane attack complex’ (MAC). The MAC is a structure that is able to form a pore in the membrane of the invading pathogen, leading to damage and lysis (Figure 1.4). Complement can be activated by three different pathways: the classical pathway, the alternative pathway and the lectin pathway: