![]()

Part One

Spatial and Temporal Variability of Canada's Cold Environments

![]()

Chapter 1

Cold Canada and the Changing Cryosphere

Hugh French1 and Olav Slaymaker2

1University of Ottawa

2University of British Columbia, Vancouver

1.1 Introduction

In a series of major reports, first initiated in 1990, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has been assessing the nature, impact and implications of current global climate change. The latest report (IPCC, 2007) concluded that warming of the climate system is unequivocal. A global temperature increase of about 0.2 °C per decade is projected for the coming two decades. It has also become clear that the cryospheric components of the climate system are closely linked to this global warming. Moreover, Canada, along with Russia and Greenland, shares the majority of the northern cryosphere.

The general thrust of the 2007 IPCC report, namely, that the Earth's climate is changing with negative consequences, has led to publication of a counter-document by the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change (NIPCC), a non-profit research and educational organization based in the USA. This report (Singer and Idso, 2009) challenges the scientific basis behind the concerns that global warming is either man-made or would have harmful effects. It is argued that twentieth century warming has been moderate and, in fact, is not unprecedented.

We do not wish to enter this global minefield; we leave that to others. Instead, the aim of this book is to simply document the changing nature of Canada's cold environments and, by implication, outline the possible global impacts. We restrict the broader discussion to the northern hemisphere.

1.2 The Cryosphere

The main components of the cryosphere are snow, river and lake ice, sea ice, glaciers and ice caps, ice shelves and ice sheets, and frozen ground (Figure 1.1). Their relevance to climate change lies in: (i) their high surface reflectivity (albedo), (ii) the fact that all three phases of water (solid, liquid and vapour) coexist over the range of the Earth's temperatures and pressures, and (iii) the large amount of latent heat associated with the phase changes between water and ice. It follows that the cryosphere has a strong impact upon the surface energy balance. The presence or absence of snow or ice at the global scale is linked to temperature differences that affect global winds and the thermohaline circulation of the oceans. The latter is initiated by the outpouring of cold arctic waters through Fram Strait in the deep channel between Greenland and the Svalbard archipelago and goes on to circulate throughout the world's oceans.

Some cryospheric components invoke positive feedback mechanisms that act to amplify change and variability. For example, a decrease in snow and sea ice extent reduces albedo and increases heat absorption. The resulting temperature increase leads to further reduction in snow and ice extent and consequently accelerated temperature rise. By contrast, other components like glaciers and permafrost act to average out short term variability and may be regarded as sensitive medium term indicators of climate change.

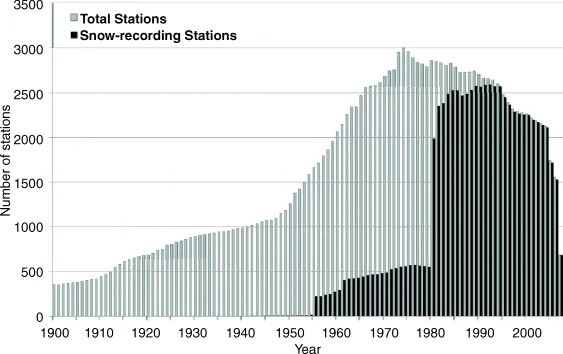

The spatial extent and global volume of the different cryospheric components are summarized in Table 1.1. Collectively, seasonally frozen ground and permafrost have the largest areal extent. As an approximation, the maximum extent of seasonally frozen ground (which includes the active layer over permafrost) is about 51% of the land area of the northern hemisphere. Snowcovers approximately 49% of the northern hemisphere land surface in mid-winter. By contrast, permanent ice in the form of glaciers and ice caps covers less than 1% of the land surface. In terms of global ice volume in the northern hemisphere, the Greenland ice sheet dominates and only a tiny fraction of ice is contained within the ice caps and glaciers of Canada, Alaska, Svalbard, Scandinavia and Russia.

Table 1.1 Area, volume and sea level equivalents of the cryospheric components.

Source: IPCC 2007, Table 4.1., Lemke et al., 2007

1.2.1 Changes in the Cryosphere

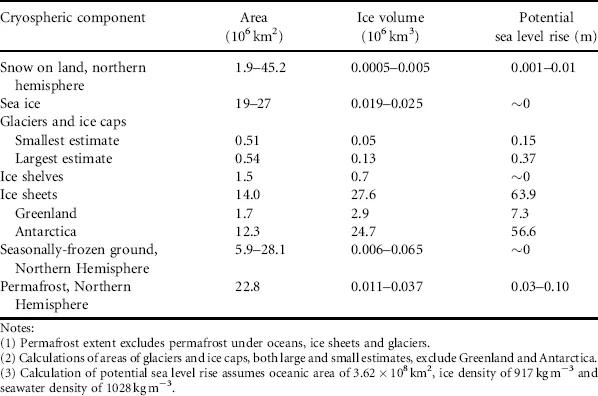

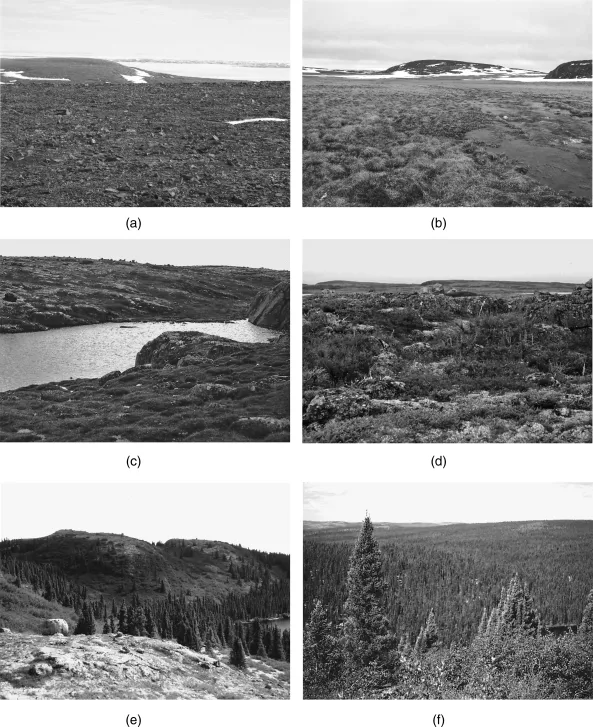

The 2007 IPCC report concluded that, since 1980, there has been a global scale decline of snow and ice, and that this decline has continued over the past decade (Figure 1.2). Satellite measurements indicate that the extent of northern hemisphere snowcover has declined by about 2% per decade since 1966 (a figure that is heavily dependent on the starting date chosen) and annual sea ice extent in the Arctic has decreased by 2.7 ± 0.6% per decade since 1978. During the same period, summer sea ice extent has decreased by 7.4 ± 2.4% per decade. There is also evidence that arctic sea ice has thinned by approximately 40% over the 1958–1977 period and in the 1990s. At the same time, field observations from many localities in the northern hemisphere suggest warming of permafrost and a decrease in its spatial extent, an increase in active layer thickness, a decrease in the depth of winter freeze in seasonally frozen areas and a decrease in duration of seasonal river and lake ice.

1.2.2 Ambiguity

These changes in Canada's cryospheric components are discussed in the following chapters. Here, we stress the ambiguity of much of the available data.

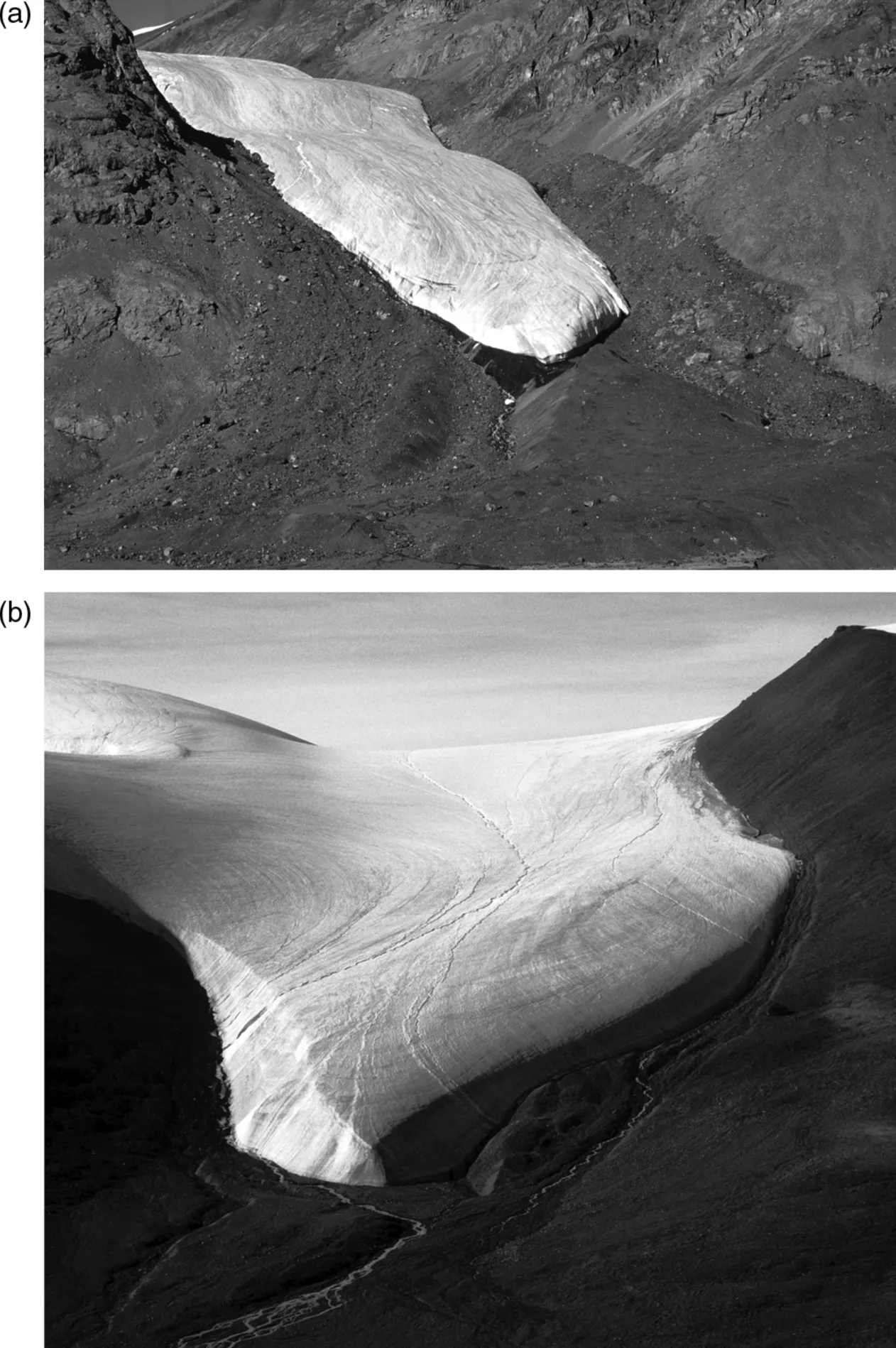

To the lay person, possibly the most visible changes that are occurring relate to the worldwide shrinkage of glaciers and ice sheets. Observations of glacier length go far back in time, with written reports from travellers and explorers as early as AD 1600. In Canada, the recent shrinkage of the Athabasca Glacier in the Canadian Rockies (see Figure 15.2) in the last 30 years is highly visible to every tourist who travels the Icefields Highway from Banff to Jasper. When global data from numerous locations in both northern and southern hemispheres are compiled, there is general agreement that glaciers started to seriously retreat after AD 1850. This trend has continued well into the second half of the twentieth century, but with significant local, regional and high-frequency variability. For example, there was a slight slow-down in glacier retreat between 1970 and 1990. However, precipitation-driven growth and advances of glaciers in western Scandinavia and New Zealand occurred during the late 1990s (Chinn et al., 2005).

A different way of looking at the retreat of glaciers and ice sheets is to examine the mass balance at the surface of a glacier (i.e. the gain or loss of snow and ice over the annual hydrological cycle). This is determined largely by climate. Therefore, climate change will affect not only the magnitude of snow accumulation and ablation, but also the length of the mass balance seasons. Unfortunately, records are biased towards logistically and morphologically accessible glaciers. Nevertheless, data from over 300 individual glaciers clearly suggest that glacier wastage in the late twentieth century is essentially a response to post-1970 global warming (Greene, 2005).

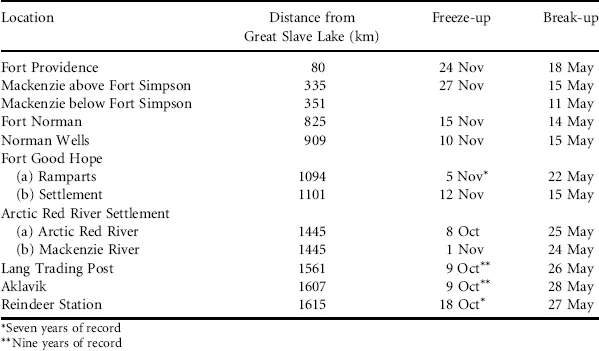

Another set of relatively long data records is provided by the freeze-up and break-up dates of river and lake ice. Such dates are of obvious importance to many human activities. In the northern hemisphere, these records extend back 150 years. A recent compilation of such records indicates that 11 out of 15 records show a significant trend towards later freeze-up, while 17 out of 25 records show a significant trend towards earlier break-up (Magnuson et al., 2000). Some of these time series data sets are shown in Figure 1.3. On balance, the average rate of change in dates for both freeze-up and break-up is approximately 5–7 days per century. On the other hand, data from some eastern Canadian rivers over the last 30 years suggest a trend towards earlier freeze-up leading to a significant decrease in open water duration (Zhang et al., 2001). In essence, it is not clear to what extent local observations on lakes and rivers reflect conditions elsewhere in the basin and it is unfortunate that there are no high elevation data included in the analysis. To further illustrate this point, Table 1.2 shows the mean freeze-up and break-up dates on the Mackenzie River, NWT, between 1946 and 1955. Naturally, there is both temporal and spatial variability in the freeze-up and break-up dates over the 1600 km distance from Great Slave Lake to the Arctic Ocean at the Beaufort Sea. This variability reflects not only latitude and climate, but also the influence of tributaries and the large water bodies at either end of the system. Russian arctic river data are equally complex; recent analyses indicate earlier freeze-up of western Russian rivers, but later freeze-up of rivers in eastern Siberia over the last 50–70 years (Smith, 2000).

Table 1.2 Mean freeze-up and break-up of the Mackenzie River, NWT, Canada, 1946–1955.

Source: Mackay, 1963

The same ambiguity characterizes recent trends in Canadian and global permafrost temperatures, as summarized by both Smith et al. (2005) and the 2007 IPCC Report (Table 1.3). For example, data from the northern Mackenzie Valley, in the continuous permafrost zone, i...