![]()

1

The Strange World of Porous Solids

Buy a bottle of good wine and enjoy it with good friends. Then fill it up with water, seal it, put it in your freezer and . . . of course you will forget it overnight. The next morning anxiously open the freezer, and there it is . . . you knew it! The bottle has broken into pieces (see Figure 1.1). What is strange about that? ‘Nothing’ you might say. Everybody knows that water expands when freezing and the bottle broke because it could not withstand the buildup of pressure that this expansion induced. No big deal, but water is a very strange substance because of its hydrogen bonds. Benzene, for instance, unlike water contracts when solidifying and so do many other liquids. In fact, most of them do. Only bismuth, germanium, silica and gallium expand when solidifying like water. So if you fill up a bottle with liquid benzene and freeze it the bottle will not break into pieces. Once again: no big deal.

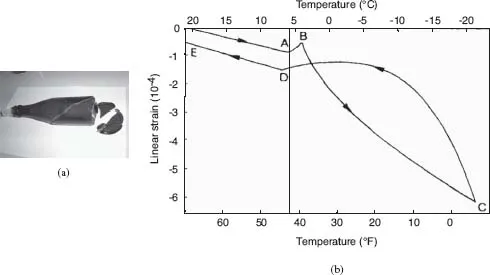

However, now consider a sample of cement paste. Cement paste is a porous solid that you can ‘fill up’, or saturate, with a liquid. So let us saturate this sample with benzene and seal it in order to prevent any benzene from escaping. Now bring it below the melting point of benzene (T = 5.5 °C = 41.9 °F). Since benzene contracts when solidifying, you may legitimately expect that the sample of cement paste will also contract. Wrong! Instead, it will slightly expand, as can be observed in Figure 1.1. Welcome to the strange world of porous solids!

What is going on there? Why does the sample of cement paste expand when benzene freezes, whereas the bottle does not? Because the porous space of the cement paste and that of the bottle are very different. The bottle is a porous solid whose porous space consists of one big pore that is almost as large as the bottle. In contrast, pores in a cement paste have sizes that range from the nanometer scale to the millimeter scale (see Figure 1.2). A pore is a confined environment, and the energy balance allowing the solid to invade a pore involves a surface energy cost because of the solid walls delimiting the pore. The smaller the pore, the more significant this surface energy cost with regard to the volume to be frozen, according to a ratio which is inverse to the pore radius. Because of the Laplace equation, the smaller the pore radius, the higher the pressure in the solid invading the pore and, therefore, the lower the temperature producing the in-pore freezing of the substance. As a result liquid-saturated pores with different sizes freeze at different temperatures, the largest pores freezing first.

However, the fact that the liquid in the largest pores freezes first does not explain the swelling of the sample when the liquid contracts as it solidifies. Basically, once formed the solid crystals have to remain in thermodynamic equilibrium with the supercooled liquid which still remains unfrozen in the smallest pores. This equilibrium is achieved when the free energy of both phases is the same. Because the molecules are more ordered in a solid than the jumble of molecules that constitute a liquid, the entropy that measures the disorder is less for the solid than for the liquid. As a result, under the same pressure the free energy of the solid increases less rapidly than that of the liquid when the temperature decreases. As the temperature decreases further below the melting point related to the pore size, in order to offset its free energy difference with the liquid due to its lower entropy, the solid becomes more pressurized than the liquid does. To produce such a pressure increase, some still unfrozen liquid is sucked into the frozen pore and freezes in its turn. The additional freezing made possible by this so-called cryosuction finally produces the observed swelling (see Figure 1.1(b)), that occurs irrespective of the change in density over the liquid−solid phase transition. In short, when pores of various sizes are put in a solid (see Figure 1.2), its behavior can become very intriguing, complex and even counter-intuitive!

We have to realize that porous solids are all around us. They can be natural (like plants, meat, rocks, stones, soils . . . ), as well as man-made (like gravels, cement, concrete, plaster, filters, gels . . . ). The human body itself, which is an assembly of bones, muscles, skin and

so on, is also a complex structure made of porous solids. Since porous solids are everywhere, they affect our day-to-day life.

If you go to the beach with your bucket and spade try building a sandcastle.Maybe something like the beautiful reproduction of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona displayed in Figure 1.3. If the sand is dry, there is no way − everything falls apart. If the sand is too wet, the same. However, if you add only a little bit of water to the sand in your bucket and turn it out your castle does not fall apart. Why? Sand is a porous material because you cannot completely fill the space with rounded grains. Capillary liquid bridges trap the little water you add within the slits between the sand grains. This water becomes strongly depressurized and sticks the grains together, giving cohesion to damp sand. If the sand is too wet the capillary bridges and the cohesion they give to the sand disappear.

Before leaving the beach, have a walk on the wet sand beside the sea. With each step you take you might expect liquid water to be squirted around your footprint in the sand. Surprise! As shown in Figure 1.4, instead of observing this squirt flow, it is exactly the opposite − each step dries out the sand around your footprint. What is this new trick of granular porous solids? Under your foot the sand does not experience only a compression but also a significant shear, particularly on the border of your footprint. Under shear the solid grains become less tangled

up and the sand becomes more porous. The enlargement of the pore space under your foot causes a liquid depression there which sucks the water from the wet sand around your foot. At the next step the water sucked towards your foot flows into the footprint you leave behind you.

The weather report you consulted before going to the beach predicted hot weather interrupted by rain, so you decided to take your leather jacket with you. If the weather is hot you know

that you will not be bothered by sweating, but if it rains your leather jacket will be the perfect raincoat. Why is this? Because your leather jacket is a porous solid that has been treated with oil: its wettability properties are such that liquid water is nonwetting and can thus not easily go through the layer of leather while water vapor is wetting and can thus easily escape.

Being near the sea, you may also see a statue that looks like the one displayed in Figure 1.5–a statue that has been badly damaged by years and years of weathering. Why does weathering happen? Because stone is a porous solid. Saline solutions are sprayed by the wind onto the surface of the statue and penetrate into the stone by capillarity. Subsequent drying increases the concentration of salt in the residual liquid until sea-salt crystallizes within the stone. Weathering is the result of the endless repetition of imbibition−drying cycles and the subsequent buildup of pressure that the crystals of sea-salt induce.

When you return home you might clean the dishes. Your sponge is hard when you pick it up, but immerse it and it becomes soft. Why? Because the sponge also is a porous solid. This time, rather than its strength, capillary bridges which drying induces within the sponge were increasing its stiffness. Saturating the sponge by immersing it causes those bridges to disappear and thus the increase in stiffness too. Letting the sponge dry again makes the capillary bridges and the increase in stiffness reappear.

The weekend is now over so you go to your laboratory and test a few samples. A material cannot withstand stresses that are arbitrarily high. When the stresses reach a critical value, the internal cohesion of the material is destroyed and the material fails. The maximum stress that the material can withstand characterizes its strength. This strength is a property that is intrinsic to the material and should therefore not depend on the rate of loading. However, if the material that you are testing is a porous solid that contains some fluid, you find out that its strength does depend on the rate of loading. Isn’t it strange? If you now extract a gassy sediment (again a porous solid) from the deep seabed and unload it gradually you will observe that failure occurs at some time during the unloading process. Again, isn’t it strange?

We are surrounded by porous solids. Since porous solids through which fluids can seep or flow are ubiquitous, they are of interest to a wide range of fields: food engineering, geosciences, civil engineering, building physics, petroleum geophysics, chemical industry, biomechanics and so on. Even though materials and fields are very diverse, all porous solids for all applications have one thing in common: they are subject to the same coupled processes such as freezing and swelling, drying and shrinkage, diffusion of liquids and creep, osmosis and expansion. Such coupled processes occur at the interface between physical chemistry and mechanics.

Since environmental engineering, petroleum geophysics, civil engineering, geotechnical engineering, biomechanics, the food industry and so on, involve processes that pertain to both physical chemistry and solid mechanics, experts in each of those two fields interact regularly. However, the interface between those two fields is not often explored, be it in textbooks or in more advanced books. This may partly explain why the dialog between experts in applied mechanics and in physical chemistry remains difficult. Experts in applied mechanics often think that experts in physical chemistry focus almost exclusively on the physical explanation of the phenomena so that the results are unsuited for quantitative engineering applications. In a similar way physical chemists think that applied mechanics experts focus almost exclusively on the mathematical modeling and thus provide no actual physical explanation for the observed phenomena. In short, an explanation before any equation can provide great help in carrying out a sound modeling. Indeed, would you be blindly confident in your numerical results if they did mimic the experimental results of Figure 1.1, but without having identified the cryosuction process that sucks liquid water towards the already frozen sites? The computer may understand but not you! Albeit the opposite is also true. When two equally attractive explanations of the same phenomenon compete, assembling equations to model the phenomenon can settle the dilemma. For instance, does a wet porous solid dry like a water pond, through vapor molecular diffusion with no significant motion of the liquid water as illustrated in Figure 1.6(a), or does the liquid water move towards the surface of the porous solid where it finally evaporates as illustrated in Figure 1.6(b)?

This book is entitled Mechanics and Physics of Porous Solids because the author believes that there is room for more physics in engineering questions that are raised by the mechanics of porous solids. The ambition here is to provide a unique and consistent framework in order to address the large variety of physical phenomena that produce a mechanical effect on porous solids. This book aims to bridge the gap between physical chemistry, which governs what happens at the level of the pore, and solid mechanics, which is the natural frame in which deformations, stresses and fluid transport are addressed and quantified at the macroscopic level of the porous material.

Intended as a first introduction, this book focuses on both the mechanics and the physics of porous solids. It also presents updated developments both in the field of unsaturated deformable porous media and in the field of the mechanics of porous media subject to phase transitions.

In order to facilitate the aforementioned interdisciplinary dialog, between experts in physical chemistry and experts in the mechanics of solids, the energy approach is chosen, which provides the common language of thermodynamics. Energy considerations will therefore be favored throughout the book.

Master students, Ph.D. students and scientists in various fields should easily be able to tackle the parts of the topics that pertain to their educational background. The expectation is that this book will generate an increasing interest in the parts that do not pertain to this background and enable the readers to expand their knowledge. As a result, various readerships are possible, and people with different backgrounds will hopefully find an interest in consulting this book.

Mechanics and Physics of Porous Solids addresses the mechanics and the physics of deformable porous materials, whose porous space is filled up with one or several fluid mixtures which interact with the solid matrix. Including neither this introductory chapter nor the concluding chapter, the book is made up of nine chapters some of which are introduced by historical comments which relate directly to the focus of the chapter. The book progressively combines basic physical and mechanical concepts that apply to fluid mixtures and to solids, in order to provide a comprehensive energy approach of their complex physical interactions. The basic concepts are reintroduced in order for the book to be self-contained. In addition, rather than writing ‘as can be easily derived’, intermediate calculations are often given, resulting in a substantial number of equations. Depending on their background readers may therefore browse or even skip some basic parts, calculations or chapters. Each chapter ends with indications for further reading. The list of proposed references is in no way exhaustive and priority has been given to books.

Chapter 2, ‘Fluid Mixtures’, is an invitation to revisit the basic concepts of thermodynamics. This is a basic chapter, and part of it may be skipped by readers having an undergraduate background in thermodynamics and fluid mixtures. After defining the chemical potential, it introduces the fundamental equality of physical chemistry, namely, the Gibbs−Duhem equation, and browses the principal results associated with ideal mixtures. The chapter revisits the electric double-layer theory. It looks into how the swelling of a porous material, filled with an electrolytic solution, originates from the excess of osmotic pressure caused by the presence of electric charges on its internal solid walls. The chapter ends with the analysis of the stability of regular fluid mixtures. These two situations are looked at in detail because they offer archetypal approaches developed throughout the book to address a variety of effects caused by nonlocal intermolecular forces and the associated stability analyses.

Chapter 3, ‘The Deformable Porous Solid’, is the natural companion of Chapter 2. It provides the relevant thermodynamic framework to elaborate the constitutive equations of a porous solid whose porous space is filled with a fluid mixture. The chapter starts by revisiting the basic concepts of continuum mechanics of solids. The two pillars of the mechanics of solids, strain and stress, are defined and related mechanical energy balances are stated. This part can be skipped by readers having the appropriate background. The second part of the chapter progressively extends these concepts to porous solids. The link between porosity variations and deformation is given first. The chapter then goes on by looking at the stress partition theorem, which splits the stress into two parts, namely, the stress sustained by the solid matrix and the part devoted to the pore pressure. The thermodynamics of a saturated porous solid is then investigated by extending the thermodynamics of fluid mixtures to solid−fluid mixtures. The porous solid itself is the material loaded by the external stress and by the pore pressure applying to its internal solid walls, irrespective of the actual cause producing the pressure. The porous solid defined in such a way is a closed system, whose thermodynamics can be carried out by extracting its energy balance from that related to the previous solid−fluid mixture. This extraction is achieved by fictitiously removing the bulk fluid mixture saturating the porous space, and whose own energy balance is independently captured by its related Gibbs−Duhem equation.

Chapter 4, ‘The Saturated Poroelastic Solid’, explores in detail the constitutive equations of both linear and nonlinear poroelastic solids. Particular attention is given to the presence of the same substance in the form of both gas bubbles and solute. The chapter gives some insights into microporoelasticity, which provides a mean field assessment of the macroscopic poroelastic properties from the porosity and the properties of the solid and fluid components. The chapter ends up by accounting for thermal effects and by considering delayed behaviors that the viscoelasticity of the solid matrix induces.

Chapter 5, ‘Fluid transport and Deformation’, analyzes how the transport of a fluid within a porous solid, and the deformation of the latter upon both the external stress and the pore pressure, are coupled phenomena. The chapter first replaces the derivation of transport laws in the context of continuum thermodynamics, and it shows how they can be derived by combining thermodynamic restrictions and an up-scaling dimensional analysis. Both molecular diffusion and advective transport laws in a porous solid are examined. When considering the gas transport, the chapter includes the possible sliding of the molecules on the internal walls of the porous network. The coupling of the deformation of the porous solid with the viscous flow of the fluid saturating the porous space is looked at later on in detail. The approach reveals that the diffusion equation governing the flow of a poorly compressible fluid i...