![]()

PART 1

Fundamental concepts of atrial fibrillation

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Anatomy of the left atrium relevant to atrial fibrillation ablation

José Angel Cabrera, Jerónimo Farré, Siew Yen Ho, Damián Sánchez-Quintana Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an arrhythmia most likely due to multiple etiopathogenic mechanisms. In spite of a still incomplete understanding of the anatomo-functional basis for the initiation and maintenance of AF, various radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) techniques have been shown to modify the substrate of the arrhythmia and/or its neurovegetative modulators, achieving in a high proportion of cases a sustained restoration of a stable sinus rhythm [1–26]. Catheter ablation techniques in patients with AF have evolved from an initial approach focused on the pulmonary veins (PVs) and their junctions with the left atrium (LA), to a more extensive intervention mainly, but not exclusively, on the left atrial myocardium and its neurovegetative innervation [27–32]. We firmly believe that progress is still required to refine the currently accepted catheter ablation approaches to AF. Because the LA is the main target of catheter ablation in patients with AF, in this chapter we review the gross morphological and architectural features of this chamber and its relations with extracardiac structures. The latter have also become relevant because of some extracardiac complications of AF ablation, such as injuries of the phrenic and vagal plexus nerves, or the devastating left atrioesophageal fistula formation [33–40].

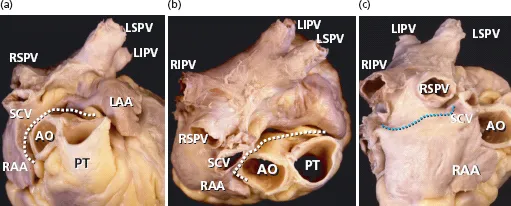

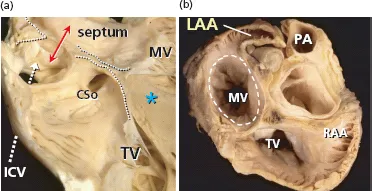

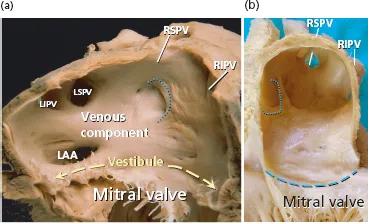

Components of the left atrium

From a gross anatomical viewpoint the LA has four components: (1) a venous part that receives the PVs; (2) a vestibule that conducts to the mitral valve; (3) the left atrial appendage (LAA); and (4) the so-called interatrial septum. We want to emphasize that the true interatrial septum is the oval fossa, a depression in the right atrial aspect of the area traditionally considered to be the interatrial septum [41–46] (Figures 1.1–1.4). At the left atrial level, a membranous valve covers this region and conceptually represents the only true interatrial septum in the sense that it can be crossed without exiting the heart. The rest of the “muscular interatrial septum” is formed by the apposition of the right and left atrial myocardia that are separated by vascularized fibro-fatty tissues extending from the extracardiac fat. This is why we prefer to use the term interatrial groove rather than muscular interatrial septum, a concept that is not only of academic interest because trans-septal punctures to access the LA should be performed through the oval fossa (Figure 1.2). Thus, a puncture throughout the interatrial groove (the muscular interatrial septum) may result in hemopericardium in a highly antico-agulated patient because blood will dissect the vascularized fibro-fatty tissue that is sandwiched between the right and left atrial myocardium at this level [47–49].

The major part of the endocardial LA including the septal and interatrial groove component is relatively smooth walled. The left aspect of the interatrial groove, apart from a small crescent-like edge, is almost indistinguishable from the parietal atrial wall. The smoothest parts are the superior and posterior walls, which make up the pulmonary venous component, and the vestibule surrounding the mitral orifice. Behind the posterior portion of the vestibular component of the LA is the anterior wall of the coronary sinus [41] (Figures 1.3 and 1.4).

The walls of the left atrium and the septum

The left atrial wall and its thickness

The walls of LA, excluding the LAA, can be described as anterior, superior, left lateral, septal, and posterior. The anterior wall is located behind the ascending aorta and the transverse pericardial sinus. From epicardium to endocardium its width is 3.3 ±1.2 mm (range 1.5–4.8 mm) in unselected necropsic heart specimens, but this wall can become very thin at the area near the vestibule of the mitral annulus where it measures an average of 2 mm in thickness in our autopsy studies. The roof or superior wall of the LA is in close proximity to the right pulmonary artery and its width ranges from 3.5 to 6.5 mm (mean 4.5 ± 0.6 mm). The thickness of the lateral wall ranges between 2.5 and 4.9 mm (mean 3.9 ± 0.7 mm) [41].

As already stated, an anatomic septum is like a wall that separates adjacent chambers so that perforation of a septal wall would enable us to enter from a chamber to the opposite one without exiting the heart. Thus, the true atrial septal wall is confined to the flap valve of the oval fossa. The flap valve is hinged from the muscular rim that, deriving from the septum secundum, is seen from the right atrial aspect of the interatrial wall. At its anteroinferior portion the rim separates the foramen ovale from the coronary sinus and the vestibule of the tricuspid valve [48] (Figure 1.2). On the left atrial aspect there is no visible rim and the flap valve overlaps the oval rim quite considerably and two horns mark the usual site of fusion with the rim (Figure 1.3 and 1.4). The measurement of the mean thickness of the atrial septum in normal hearts at the level of the anteroinferior portion of the muscular rim is 5.5 ± 2.3 mm, and the mean thickness of the flap valve is 1.5 ± 0.6 mm [41]. These results agree with previously published echocardiographic studies [50]. The major portion of the rim around the fossa is an infolding of the muscular atrial wall that is filled with epicardial fat. Superiorly and posteriorly there is an interatrial groove, also known as Waterston’s groove, whose dissection permits the separation of the right and left atrial myocardial walls and to enter the LA without transgressing into the right atrium. Anteriorly and inferiorly, the rim and its continuation into the atrial vestibules overlies the myocardial masses of the ventricles from which they are separated by the fat-filled inferior pyramidal space [48,51] (Figures 1.2–1.4).

The posterior wall of the LA is a target of currently used ablation procedures in patients with AF. Early surgical interventions aimed at reducing the critical mass of atrial tissues created long transmural linear lesions incorporating the posterior LA wall. The posterior wall of the LA is related to the esophagus and its nerves (vagal nerves) and the thoracic aorta, and its inferior portion is related to the coronary sinus. In a previous study in 26 unselected human heart specimens the overall thickness of the posterior LA wall was 4.1 ± 0.7 mm (range 2.5–5.3 mm) [41]. In a subsequent study we measured the thickness of the posterior wall from the epicardium to endocardium, obtaining sagittal and transverse sections through the LA at three levels (superior, middle, and inferior close to the coronary sinus) in three different LA regions (right venoatrial junction, mid-posterior atrial wall, and left venoatrial junction) [52]. We also analyzed the myocardial content of the LA wall at all these predefined sites. The region with the thickest myocardial content was the mid-posterior LA wall (2.9 ± 0.5 mm, range 0.6–4.2 mm). The inferior level, immediately superior to the coronary sinus and between 6 and 15 mm from the mitral annulus, had the thickest posterior LA wall (6.5 ± 2.5 mm, range 2.8–12 mm). The latter thickness was due to a rather bulky myocardial layer (4.3 ± 0.8 mm) and the presence of a profuse amount of fibro-fatty tissue, both components being less developed at more superior levels of the posterior LA wall. The wall at the plane of the right or left venoatrial junction had the thinnest musculature (2.2 ± 0.3 mm, range 1.2–4.5 mm) and a very scanty content of fibro-fatty tissue [52]. In some samples of histological sections obtained at the PV and posterior atrial wall, the myocardial layer had small areas of discontinuities that were filled with fibrous tissue [42,53].

The myoarchitecture of the left atrial wall

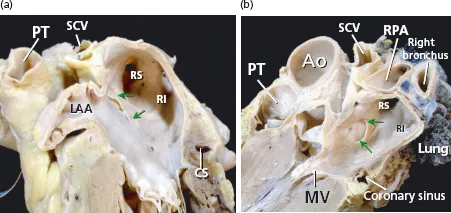

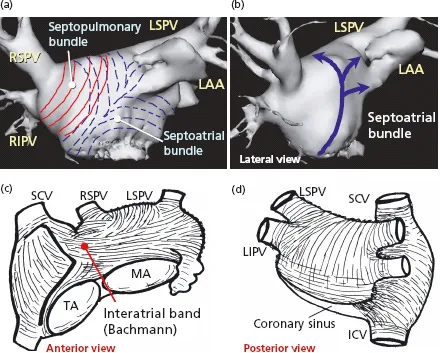

Detailed dissections of the subendocardial and subepicardial myofibers along the entire thickness of the LA walls have shown a complex architecture of overlapping bands of aligned myocardial bundles [41,51] (Figures 1.5 and 1.6). The term “fibers” describes the macroscopic appearance of strands of cardiomyocytes. These fibers are circumferential when they run parallel to the mitral annulus and longitudinal when they are approximately perpendicular to the mitral orifice. Although there are some individual variations, our epicardial dissections of the LA have shown a predominant pattern of arrangement of the myocardial fibers [41]. On the subepicardial aspect of the LA, the fibers in the anterior wall consisted of a main bundle that was parallel to the atrioventricular groove. This was the continuation of the interatrial bundle (Bachmann’s bundle) [54], which could be traced rightward to the junction between the right atrium and the superior caval vein. In the LA, the interatrial bundle was joined inferiorly at the septal raphe (the portion that is buried in the atrial septum) by fibers arising from the anterior rim of the oval foramen. Superiorly, it blended with a broad band of circumferential fibers that arose from the anterosuperior part of the septal raphe to sweep leftward into the lateral wall. Reinforced superficially by the interatrial bundle, these circumferential fibers passed to either side of the neck of the atrial appendage to encircle the appendage, and reunited as a broad circumferential band around the inferior part of the posterior wall to enter the posterior septal raphe (Figures 1.5 and 1.6). The epicardial fibers of the superior wall are composed of longitudinal or oblique fibers, (named by Papez as the “septopulmonary bundle” in 1920) [55] that arise from the anterosuperior septal raphe, beneath the circumferential fibers of the Bachmann’s bundle. As they ascend the roof, they fan out to pass in front, between, and behind the insertions of the pulmonary veins and the myocardial sleeves that surround the venous orifices. On the posterior wall, the septopulmonary bundle often bifurcates to become two oblique branches. The leftward branch fused with, and was indistinguishable from, the circumferential fibers of the anterior and lateral walls, whereas the rightward branch turned into the posterior septal raphe. Often, extensions from the rightward branch passed over the septal raphe to blend with right atrial fibers and others toward the septal mitral valve annulus, forming a line that marked an abrupt change in subendocardial fiber orientation.

On the subendocardial aspect of the LA, most specimens showed a common pattern of general architecture. The dominant fibers in the anterior wall were those orginating from a bundle described by Papez as the septoatrial bundle [55]. The fibers of this bundle ascended obliquely from the anterior interatrial raphe and combined with longitudinal fibers arising from the vestibule. They passed the posterior aspect of the LA between the left and right pulmonary veins, blending with longitudinal or oblique fibers of the septopulmonary bundle from the subepicardial layer. The septoatrial bundle also passed leftward, superior and inferior to the mouth of the atrial appendage to reach the lateral and posterior walls. Some of these fibers encircled the mouth of the LA appendage and continued into the pectinate muscles within the appendage (Figures 1.5 and 1.6). The subendocardial fibers at the orifices of the PVs were usually loop-like extensions from the longitudinal fibers. These fibers became circular at varying distances into the venous walls and were continuous with the subepicardial fibers. In ...