![]()

CHAPTER 1

Transdermal Drug Delivery

1.1 Genesis of transdermal drug delivery

The administration of chemical agents to the skin surface has long been practised, whether for healing, protective or cosmetic reasons. Historically, the skin was thought to be totally impervious to exogenous chemicals [1]. Thus, topical drug therapy typically involved the localized administration of medicinal formulations to the skin, generally when the skin surface was breached by disease or infection and a route of drug absorption into the deeper cutaneous layers was consequently open. However, once it was understood that the skin was a semipermeable membrane rather than a totally impermeable barrier, new possibilities arose for the use of this route as a portal for systemic drug absorption.

In the early twentieth century it was recognized that more lipophilic agents had increased skin permeability. The barrier properties of the skin were attributed specifically to the outermost layers in 1919 [2]. Scheuplein and co-workers thoroughly investigated skin permeability to a wide range of substances in vitro [3]. They modelled skin as a three-layer laminate of stratum corneum, epidermis and dermis, with drug permeation driven by Fickian diffusion. By digesting the epidermal layer, stratum corneum was separated from the lower layers of the skin and was determined to be the principal barrier to drug absorption.

Transdermal drug delivery refers to the delivery of the drug across intact, healthy skin and into the systemic circulation. The diffusive process by which this is achieved is known as percutaneous absorption. Thus, classical topical formulations can be distinguished from those intended for transdermal drug delivery in that, whilst the former are generally applied to a broken, diseased or damaged integument, the latter are used exclusively on healthy skin where the barrier function is intact.

It is, indeed, fortuitous for all of us that the skin is a self-repairing organ. This ability, together with the barrier protective properties associated with the integument, is a direct function of skin anatomy. Therefore, in order to develop an effective approach to transdermal drug delivery, it is necessary to be aware of how skin anatomy restricts the percutaneous absorption of exogenously applied chemicals. So effective is the skin as a barrier to the external environment that, even now, the majority of licensed preparations applied to the skin are aimed at delivering the drug for a local, rather than a systemic, action.

1.2 Skin anatomy

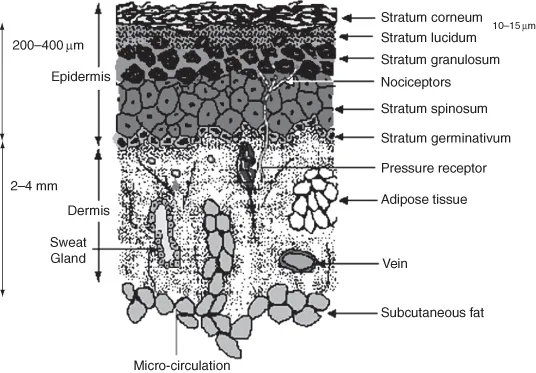

As the largest and one of the most complex organs in the human body, the skin is designed to carry out a wide range of functions [4]. Thus, the skin forms a complex membrane with a nonhomogenous structure (Figure 1.1). It contains and protects the internal body organs and fluids, and exercises environmental control over the body in respect of temperature and, to some extent, humidity. In addition, the skin is a communicating organ, relaying the sensations of heat, cold, touch, pressure and pain to the central nervous system.

1.2.1 The epidermis

The multilayered nature of human skin can be resolved into three distinct layers. These are the outermost layer, the epidermis, beneath which lies the much larger dermis and, finally, the deepest layer, the subcutis. The epidermis, which is essentially a stratified epithelium, lies directly above the dermo-epidermal junction. This provides mechanical support for the epidermis and anchors it to the underlying dermis. The junction itself is a complex glycoprotein structure about 50 nm thick [5].

Directly above the undulating ridges of the dermo-epidermal junction lies the basal layer of the epidermis, the stratum germinativum. This layer is single-cell in thickness with columnar-to-oval shaped cells, which are actively undergoing mitosis. As the name implies, the stratum germinativum generates replacement cells to counterbalance the constant shedding of dead cells from the skin surface. In certain disease states, such as psoriasis, the rate of mitosis in this layer is substantially raised in order to compensate for a diminished epidermal barrier, the epidermal turnover time being as fast as four days. As the cells of the basal layer gradually move upwards through the epidermis, they undergo rapid differentiation, becoming flattened and granular. The ability to divide by mitosis is lost. Directly above the stratum germinativum is a layer, several cells in thickness, in which the cells are irregular and polyhedral in shape. This layer is the stratum spinosum, and each cell has distinct spines or prickles protruding from the surface in all directions. Although they do not undergo mitosis, the cells of this layer are metabolically active. The prickles of adjacent cells interconnect via desmosomes or intercellular bridges. The increased structural rigidity produced by this arrangement increases the resistance of the skin to abrasion.

As the epidermal cells migrate upwards towards the skin surface they become flatter and more granular in appearance, forming the next epidermal layer, which is the stratum granulosum, consisting of a few layers of granular cells. Their appearance is due to the actively metabolizing cells producing granular protein aggregates of keratohyalin, a precursor of keratin [6]. As cells migrate through the stratum granulosum, cell organelles undergo intracellular digestion and disappear. The cells of the stratum granulosum die due to degeneration of the cell nuclei and metabolic activity ceases towards the top of this layer. A further differentiation of cells above the stratum granulosum can be seen in sections taken from thick skin, such as on the palm of the hand or the sole of the foot. This distinct layer of cells, which is now substantially removed from nutrients supplied via the dermal circulation, is the stratum lucidum. The cells of this layer are elongated, translucent and anuclear.

1.2.2 The stratum corneum

The stratum corneum, or horny layer, is the outermost layer of the epidermis, and thus the skin. It is now well accepted that this layer constitutes the principal barrier for penetration of most drugs [7]. The horny layer represents the final stage of epidermal cell differentiation. The thickness of this layer is typically 10 μm, but a number of factors, including the degree of hydration and skin location, influence this. For example, the stratum corneum on the palms and soles can be, on average, 400–600 μm thick [7] whilst hydration can result in a 4-fold increase in thickness [8].

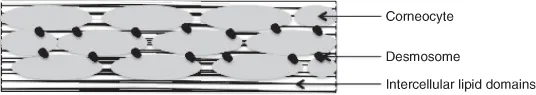

The stratum corneum consists of 10–25 rows of dead keratinocytes, now called corneocytes, embedded in the secreted lipids from lamellar bodies [7]. The corneocytes are flattened, elongated, dead cells, lacking nuclei and other organelles [9]. The cells are joined together by desmosomes, maintaining the cohesiveness of this layer [10]. The heterogeneous structure of the stratum corneum is composed of approximately 75–80% protein, 5–15% lipid and 5–10% other substances on a dry weight basis [11].

The majority of protein present in the stratum corneum is keratin and is located within the corneocytes [11]. The keratins are a family of α-helical polypeptides. Individual molecules aggregate to form filaments (7–10 nm diameter and many microns in length) that are stabilized by insoluble disulphide bridges. These filaments are thought to be responsible for the hexagonal shape of the corneocyte and provide mechanical strength for the stratum corneum [12]. Corneocytes possess a protein rich envelope around the periphery of the cell, formed from precursors, such as involucrin, loricrin and cornifin. Transglutaminases catalyze the formation of γ-glutamyl cross-links between the envelope proteins that render the envelope resistant and highly insoluble. The protein envelope links the corneocyte to the surrounding lipid enriched matrix [10].

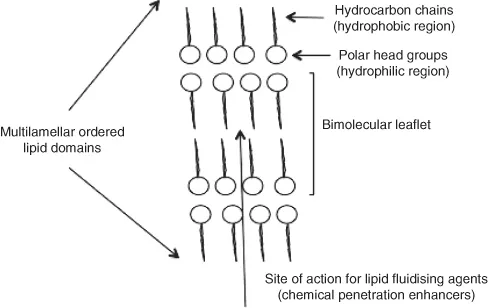

The main lipids located in the stratum corneum are ceramides, fatty acids, cholesterol, cholesterol sulphate and sterol/wax esters [11,12]. These lipids are arranged in multiple bilayers called lamellae (Figure 1.2). Phospholipids are largely absent, a unique feature for a mammalian membrane. The ceramides are the largest group of lipids in the stratum corneum, accounting for approximately half of the total lipid mass [13], and are crucial to the lipid organization of the stratum corneum [10].

The bricks and mortar model of the stratum corneum (Figure 1.3) is a common representation of this layer [8]. The bricks correspond to parallel plates of dead keratinized corneocytes, and the mortar represents the continuous interstitial lipid matrix. It is important to note that the corneocytes are not actually brick-shaped, but rather are polygonal, elongated and flat (0.2–1.5 μm thick and 34.0–46.0 μm in diameter) [9]. The ‘mortar’ is not a homogenous matrix. Rather, lipids are arranged in the lamellar phase (alternating layers of water and lipid bilayers), with some of the lipid bilayers in the gel or crystalline state [14]. The extracellular matrix is further complicated by the presence of intrinsic and extrinsic proteins, such as enzymes. The barrier properties of the stratum corneum have been assigned to the multiple lipid bilayers residing in the intercellular space. These bilayers prevent desiccation of the underlying tissues by inhibiting water loss and limit the penetration of substances from the external environment [14].

1.2.3 The dermis

This region, also known as the corium, underlies the dermo-epidermal junction and varies in thickness from 2 to 4 mm. Collagen, a fibrous protein, is the main component of the dermis and is responsible for the tensile strength of this layer. Elastin, also a fibrous protein, forms a network between the collagen bundles and is responsible for the elasticity of the skin and its resistance to external deforming forces. These protein components are embedded in a gel composed largely of mucopolysaccharides. The skin appendages such as the sebaceous and sweat glands, together with hair follicles, penetrate this region. Since these open to the external environment they present a possible entry point into the skin.

The dermis has a rich blood supply extending to within 0.2 mm of the skin surface and derived from the arterial and venous systems in the subcutaneous tissue. This blood supply consists of microscopic vessels and does not extend into the epidermis. Thus, a drug reaching the dermis through the epidermal barrier will be rapidly absorbed into the systemic circulation, a key advantage in the use of microneedles to by-pass the barrier to drug penetration offered by the stratum corneum.

1.2.4 Skin appendages

The skin appendages comprise the hair follicles and associated sebaceous glands, tog...