![]()

Chapter 1

Molecular Rings Studded With Jewels

Fortune Goddess, in your glory, in your honor, stern Kama,

Bangles, finger-rings and bracelets I will lay before your Temple.

V. Bryusov

Readers of this book, whether or not they are students of organic chemistry, will all be aware of the vital role of proteins, fats and carbohydrates in life processes. Experience has shown that considerably less is usually known about another class of compounds which have a similar importance in the chemistry of life, namely the heterocyclic compounds or, in short, heterocycles. What are heterocycles?

1.1 From Homocycle to Heterocycle

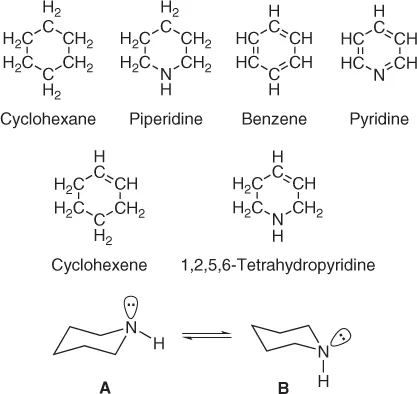

It is rumored that the Russian scientist Beketov once compared heterocyclic molecules to jewelry rings studded with precious stones. Several carbon atoms thus make up the setting of the molecular ring, while the role of the jewel is played by an atom of another element, a heteroatom. In general, it is the heteroatom which imparts to a heterocycle its distinctive and sometimes striking properties. For example, if we change one carbon atom in cyclohexane for one nitrogen atom, we obtain a heterocyclic ring, piperidine, from a homocyclic molecule. In the same way, we can derive pyridine from benzene, or 1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine from cyclohexene (Figure 1.1).

A great many heterocyclic compounds are known. They differ in the size and number of their rings, in the type and number of heteroatoms, in the positions of the heteroatoms and so on. The rules of their classification help to orient us in this area.

Cyclic hydrocarbons are divided into cycloalkanes (cyclopentane, cyclohexane, etc.), cycloalkenes (e.g., cyclohexene) and aromatic hydrocarbons (with benzene as the main representative). The most basic general classification of heterocycles is similarly divided into heterocycloalkanes (e.g., piperidine), heterocycloalkenes (e.g., 1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine) and heteroaromatic systems (e.g., pyridine, etc.). Subsequent classification is based on the type of heteroatom. On the whole, heterocycloalkanes and heterocycloalkenes show comparatively small differences when compared with related noncyclic compounds. Thus, piperidine possesses chemical properties very similar to those of aliphatic secondary amines, such as diethylamine, and 1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine resembles both a secondary amine and an alkene.

An interesting feature of heterocycloalkanes and heterocycloalkenes is the possibility of their existence in several geometrically distinct nonplanar forms which can quite easily (without bond cleavage) equilibrate with each other. Such forms are called conformations. For instance, piperidine exists mainly in a pair of chair conformations in which the internal angle between any pair of bonds is close to tetrahedral (109° 28′) to minimize steric strain. In these two chair conformations (Figure 1.1), the N–H proton is in either the equatorial (A) or axial (B) position, the first being slightly preferred.

By contrast, the heteroaromatic compounds, as the most important group of heterocycles, possess highly specific features. Historically, the name ‘aromatic’ for derivatives of benzene, naphthalene and their numerous analogues came from their characteristic physical and chemical properties. Aromatic compounds differ from other groups in possessing thermodynamic stability. Thus, they are resistant to heating and tend to be oxidized and reduced with difficulty. On treatment with electrophilic, nucleophilic and radical agents, they mainly undergo substitution of hydrogen atoms rather than the addition reactions to multiple bonds which are typical for ethylene and other alkenes. Such behavior results from the peculiar electronic configuration of the aromatic ring. We consider in the next section the structure of benzene and some parent heteroaromatic molecules.

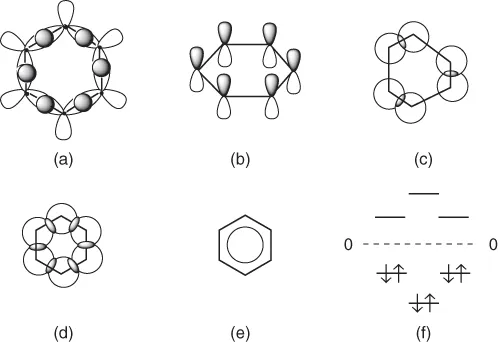

1.2 Building Heterocycles From Benzene

Each carbon atom in the benzene molecule formally participates in bond formation with its four atomic orbitals, each occupied by one electron. Three of these orbitals are hybridized and are called sp2-orbitals. Their axes lie in the same plane and are directed from each other at an angle of 120°. These atomic orbitals overlap similar orbitals of adjacent carbon atoms or the s-orbitals of hydrogen atoms, thereby forming the ring framework of six carbon–carbon bonds and six carbon–hydrogen bonds (Figure 1.2a). The molecular orbitals and bonds thus formed are called σ-orbitals and σ-bonds, respectively. The fourth electron of the carbon atom is located in an atomic p-orbital, which is dumbbell shaped and has an axis perpendicular to the ring plane (Figure 1.2b). If the p-orbitals merely overlapped in pairs, the benzene molecule would possess the cyclohexatriene structure with three single and three conjugated double bonds, as reflected in the classic representation of benzene—the Kekulé structure (Figure 1.2c). However, in reality, the benzene ring is a regular hexagon, which indicates equal overlap of each p-orbital with its two neighboring p-orbitals, resulting in the formation of a completely delocalized π-electron cloud (Figure 1.2d, e).

Thus, in the benzene molecule as well as in the molecules of other aromatic compounds, we observe a new type of carbon–carbon bond called ‘aromatic’, which is intermediate in length between a single and a double bond. Standard aromatic C–C bond lengths are close to 1.40

, whereas the C–C distance is 1.54

in ethane and 1.34

in ethylene.

The high stability of the benzene molecule is explained by the energetic picture available from quantum mechanics. Benzene has six molecular π-orbitals. Three of these π-orbitals (bonding orbitals) lie below the nonbonding energy level and are occupied by six electrons with a large energy stabilization. The remaining three are above the nonbonding level (antibonding orbitals). Occupation of the bonding orbitals leads to the formation of strong bonds and stabilizes the molecule as a whole. Incomplete occupation of bonding orbitals, and especially the occupation of antibonding orbitals, results in considerable destabilization. Figure 1.2f shows that all three bonding orbitals in benzene are completely occupied. Hence, it is often said that benzene has a stable aromatic π-electron sextet, a concept that can be compared in its importance to the inert octet cloud of neon or the F− anion.

In addition to the π-electron sextet, stable aromatic arrangements can also be formed by 2, 10, 14, 18 or 22 π-electrons. Such molecules contain cyclic sets of delocalized π-electrons. For example, the aromatic molecule naphthalene possesses 10 π-electrons. The number of electrons required for a stable aromatic configuration can be calculated by the 4n + 2 ‘Hückel rule’, where n = 0, 1, 2, 3 and so on, which was suggested by the German scientist Hückel in the early 1930s.1

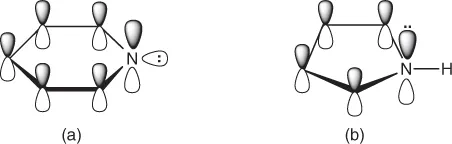

The electronic configuration of the pyridine molecule is very similar to that of benzene (Figure 1.3a). Both compounds contain an aromatic π-electron sextet. However, the presence of the nitrogen heteroatom in the case of pyridine results in significant changes in the cyclic molecular structure. First, the nitrogen atom has five valence electrons in the outer shell, in contrast with the carbon atom which has only four. Two take part in the formation of the skeletal carbon–nitrogen σ-bonds, and a third electron is utilized in the aromatic π-cloud. The two remaining electrons are unshared, their sp2-orbitals lying in the plane of the ring. Owing to the availability of this unshared pair of electrons, the pyridine molecule undergoes many additional reactions over and above those which are characteristic of benzene or other aromatic hydrocarbons. Second, nitrogen is a more electronegative element than carbon and therefore attracts electron density. The distribution of the π-electron cloud in the pyridine ring is thus distorted (see Chapter 2).

Heterocyclic compounds include examples containing many other heteroatoms such as phosphorus, oxygen, sulfur and so on. By substitution of a ring carbon atom we may formally transform benzene into phosphabenzene or pyrylium and thiapyrylium cations (Figure 1.4). Note that a six-membered ring which includes oxygen or another group VI element can only be aromatic if the heteroatom...