1 Preventing heart failure

Introduction

Epidemiology

Heart failure is pandemic amongst industrialized nations. In the United States alone it is estimated that there are over 5 million individuals suffering from heart failure, and each year an estimated 555,000 new cases are diagnosed [1]. The impact of heart failure on the health care system, and on society in general, is staggering. It is the leading cause of hospitalization in Medicare beneficiaries and, overall, it results in over 1 million hospitalizations each year. The cost to the United States healthcare system was estimated in 2007 to be more than $33 billion annually [1]. Although therapeutic advances have improved survival in heart failure patients, estimated 5-year mortality is still in the range of 50% [2].

On top of this disturbing picture is the certainty that heart failure prevalence will increase substantially over the next several decades. The major reasons for this are outlined in Table 1.1. The most important of these is the aging of the population. Heart failure is predominantly a disease of older people [3] and the population of industrialized nations is increasing in age. In the U.S., the number of individuals greater than 65 years will nearly double from 35 million in the year 2000 to over 70 million in 2030 [4]. Data from the Framingham study indicates that the lifetime risk of developing heart failure for individuals who are age 40 is 21% for men and 20% for women [5]. Similarly alarming figures have been reported from European studies. The Rotterdam study reported a lifetime risk of heart failure in individuals of 55 years to be 33% in men and 28.5% in women [6]. Thus, growth in the segment of the population that is at the highest risk for developing heart failure will substantially increase future incidence and prevalence.

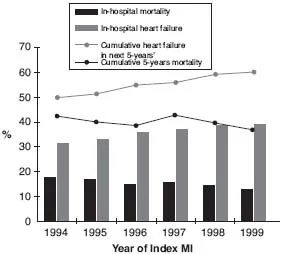

Along with the aging of the population, patients with a variety of cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease (CAD), valvular lesions, or congenital abnormalities, now experience much better outcomes and longer survival than in the past. In particular, aggressive revascularization strategies have resulted in improved survival of patients following a myocardial infarction (MI). Many of these patients, however, have experienced some degree of myocardial injury and are at risk of further structural changes (i.e., cardiac remodeling) that can lead to progressive deterioration in cardiac function and increased mortality over time [7]. A recent publication points out the reciprocal relationship between increased survival of older patients who suffer a MI and higher risk for developing heart failure in the future (Figure 1.1). In this work, Ezekowitz and colleagues noted that in a cohort of 4291 MI survivors >65 years who were without heart failure during their index hospitalization, 71% developed heart failure within 5 years with nearly two-thirds of the cases presenting with the first year post-MI [8].

Another factor that has resulted in the growth of the heart failure population is, paradoxically, the improved survival of patients with chronic heart

Table 1.1 Reasons for the Increasing Prevalence of Heart Failure

| 1. | Aging of the population. |

| 2. | Improved survival in patients with other cardiovascular conditions (e.g., myocardial infarction, valvular heart disease, congenital lesions). |

| 3. | Impact of current therapy (e.g., ACEIs, ARBs, aldosterone blockers, BBs, ICDs) in prolonging survival of patients with existing heart failure. |

| 4. | Increased incidence and prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome in the population. |

| 5. | Better and earlier recognition of the presence of heart failure. |

| 6. | Reduction in premature mortality due to infectious disease in developing countries. |

ACEIs = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors;

ARBs = angiotensin receptor blockers;BBs = beta-blockers;

ICDs = intracardiac defibrillators.

ARBs = angiotensin receptor blockers;BBs = beta-blockers;

ICDs = intracardiac defibrillators.

failure. As the use of lifesaving therapies such as beta-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, intracardiac defibrillators (ICDs) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) becomes more widespread, a greater number of patients will survive a longer period of time with heart failure. While this is unarguably a positive development, improved therapy is in most cases only palliative. Moreover, the increasing number of patients who are well treated with these therapies has resulted in the emergence of a cohort of patients with ‘advanced chronic HF’ who have severely limiting symptoms, marked hemodynamic impairment, and increased hospitalizations and mortality [9]. The implications of this development is that this “emerging cohort of patients with advanced chronic heart failure (ACHF) represents a population for which additional treatments are required”.

Over the past several years there has been an alarming increase in the incidence and prevalence of obesity [10], diabetes (mostly Type II) [11], and the metabolic syndrome [12], all of which have been shown to be associated with increased risk of developing heart failure. These conditions are strongly related [11] to each other and while genetic factors

Figure 1.1 Temporal Trends in Mortality Rate and the Development of Heart Failure. Black bars indicate in-hospital mortality rate, and gray bars indicate in-hospital heart failure rate. Gray line indicates cumulative heart failure in the next 5 years for patients who survived index hospitalization, and black line indicates the cumulative 5-year mortality. X-axis indicates year of hospitalization for index myocardial infarction (MI).

From: Ezekowitz JA, Kaul P, Bakal JA, Armstrong PW, Welsh RC, McAlister FA. Declining in-hospital mortality and increasing heart failure incidence in elderly patients with first myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(1):13–20. Reproduced by permission of Elsevier.

are involved, they are caused to a large degree by profoundly unhealthy dietary and exercise patterns [13]. As will be discussed later in the chapter, while both diet and exercise are lifestyle choices that are amenable to preventive strategies, there is little evidence that such strategies will reduce the risk of heart failure in the future.

Finally, there has been increased emphasis on early recognition and improved accuracy of diagnosing heart failure. A variety of imaging and blood chemistry tests are being used for that purpose. Probably the most promising of these is the use of biomarkers in the diagnosis of patients with heart failure [14–16]. As these tests are more widely applied as screening tools, the prevalence of heart failure is likely to increase substantially. The reason for this is that they will provide a mechanism for the earlier recognition of heart failure in patients with either minimal or ambiguous symptoms.

While most of the current epidemiologic information about heart failure originates from industrialized countries, there has been a sizeable shift in disease patterns in the developing world. As infectious diseases decline in prevalence due to more effective prevention and treatment, there has been a transition in patterns of morbidity and mortality to chronic degenerative diseases. This trend will only accelerate in the future as these countries experience changes in lifestyle, including modifications in diet, exercise patterns, smoking, and obesity that will put large segments of the population at risk for CV disease. The prevalence and incidence data about heart failure in developing countries is scanty and probably misleading since it is based on referral or hospital based data [17]. Nonetheless, there is evidence that in Asia hospitalization rates from heart failure are increasing [18].

Heart failure as a continuum

In seeking ways to most effectively deal with the increasing worldwide burden of heart failure it is worthwhile considering the sequence of events that led to its development. Heart failure is a clinical syndrome that is the consequence of a variety of diseases, most of which directly affect the heart. Although there are numerous causes of heart failure, the common denominator of these diverse etiologies is that they either directly damage the myocardium (e.g., MI or exposure to myocardial toxins) or they expose it to increased levels of wall stress (e.g., hypertension or valvular lesions). The initial insult to the myocardium then activates a complex process in which the heart attempts to compensate for a loss in contractile performance and/or an increase in wall stress through alterations in structure. Many of the compensatory changes are mediated by activation of neurohoromonal systems such as the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and renin angiotensin system (RAS) [19]. Neurohormonal activation is widespread occuring systemically [19] and locally within the heart itself [20]. The direct consequences on the heart include cardiac remodeling characterized by hypertrophy, dilatation, deposition...