![]()

Chapter 1

Methodological Aspects

1.1. Definitions

Physical ageing: ageing that does not involve a change in chemical structure — for example ageing by structural relaxation in a glassy state, ageing resulting from the migration of plasticizers or the absorption of solvents, etc.

Chemical ageing: ageing involving a change in the chemical structure of the macromolecules. Oxidation is a type of chemical ageing, which may coexist with other types — physical or chemical.

Natural ageing: ageing in operating conditions.

Accelerated ageing: ageing carried out in such conditions as to make the change of the properties faster than in natural ageing so that definitive information can be obtained within acceptable timescales.

Lifetime: the material belongs to a structure, a system. Ideally, the lifetime is that of the system; it can be defined as that age of the system beyond which the probability of failure exceeds a threshold, conventionally defined, based on technological or economical criteria specific to the application. When the change in the probability of failure is linked to the change in a material which is part of the system, and we can establish a link between that probability and a value of a property of that material, it is possible to define an end-of-life criterion for that property and label the age of the material at which that criterion has reached its “lifetime”. It is important to note that the lifetime is a characteristic which is specific to a property, an environment and an application, not an inherent characteristic of the material.

Embrittlement: change expressed as an increase in the probability of fracturing under a given mechanical load. Embrittlement is a particularly important phenomenon for the following reasons: whatever the functions of the material, it is usually not acceptable for it to lose its geometric integrity by cracking or fracture. Moreover, it is very commonplace for its fracture properties to evolve more quickly than other properties. Finally, embrittlement is often a catastrophic phenomenon in the case of plastics — i.e. the behavior changes suddenly from a ductile-tough regime to a brittle regime, with the characteristic values changing sometimes by more than an entire order of magnitude. This sudden change corresponds to a sharp increase in the probability of failure in a great many applications, which reaffirms the interest of this type of criterion.

Deterministic approach, probabilistic approach: this book is dedicated to a deterministic approach to lifetime prediction. This involves establishing a kinetic model of ageing, constructed based on a hypothesis of mechanism, expressing the evolution of a given property depending on the relevant environmental parameters (temperature, light intensity, pressure of oxygen, etc.). However, these parameters, which may be set and controlled during accelerated ageing tests, vary over time and according to the site of exposure in the case of natural ageing, without these variations necessarily being known to the user. In these circumstances, the deterministic model may gain by being associated with a probabilistic model. On the other hand, to our knowledge there is no probabilistic approach which, on its own, could yield a reliable prediction of lifetime using the results of accelerated ageing testing.

Durability: this term may have two different meanings. Firstly, it may be taken as a synonym of longevity, i.e. likelihood to endure. It is also used to denote the discipline of the study of ageing in the broader sense.

Stabilization: change (usually minor) in structure (internal stabilization) or composition (external stabilization by incorporation of additives or fillers) leading to an increased lifetime.

Synergy, antagonism: these terms will only be used if they have a quantitative counterpart. If a cause

C1 has an effect

E1 and a cause

C2 has an effect

E2 in similar conditions, e.g. if

C1 and

C2 are different stabilizers (with equal mass fractions),

E1 and

E2 being the corresponding lifetimes, and if the mix (with the same mass fraction) has effect

E, we would say that there is synergy if

and there is antagonism if

. For instance, it makes no sense to speak of temperature/radiation synergy because the two factors can neither be separated nor combined. It makes no sense to carry out an irradiation test without temperature. Note in passing the particular status of the temperature parameter. It is not, as is frequently stated, a cause of ageing. The cause is always the instability of the material; the temperature is merely (one of) the parameter(s) that influences the kinetics. The concept of synergy/antagonism only makes sense if it is quantifiable, which is only possible if the two causes can be represented by extensive values, in the same system of units.

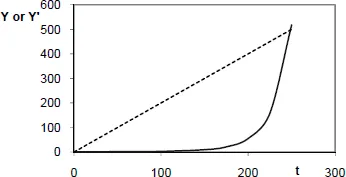

Induction period: in many instances of oxidation, the kinetic curves reveal strongly non-linear behavior. The oxidation rate is so slow in the initial period of exposure that no change is detectable, possibly for a very long time. After a certain amount of time, however, the reaction speeds up and its effects become measurable. This period is called the induction time/period. The existence of a phenomenon of induction may have a number of causes:

– it is a kinetic behavior intrinsic to the process of oxidation. The end of the induction period does not correspond to a discontinuity. Using a logarithmic scale for the conversion ratio, we would get a monotonous curve. This is illustrated by Figure 1.1, which shows an arbitrary kinetic law: Y = exp(0.01t)2 (solid line), the unit of time being, for example, one day. Let us assume that the sensitivity of the measurement of Y is 10 units; it is then tempting to conclude that no reaction occurs for an induction period of around 150 days. Here, the apparent discontinuity of the curve Y = f(t), even more marked in a curve Y= g(logt), is related to the fact that the measured value exceeds a threshold corresponding to the limit of sensitivity of the method used. If we used a method 1,000 times more sensitive, we would see a shorter induction period;

– the measured value only changes beyond a certain conversion ratio of the reaction. As we shall see, this is often the case with fracture properties;

– the material contains a stabilizer which is consumed by the reaction, but which protects the polymer as long as its concentration remains above a certain threshold. If an induction phenomenon exists for the non-stabilized polymer, the presence of a stabilizer will result in a longer induction period.

These three causes may be combined.

Kinetic model: a mathematical tool which ranges from a simple proportionality relation to a set of over 20 coupled non-linear differential equations, the aim of which is to describe the evolution over time of one or more properties of the material for given values of the influencing environmental parameters, which must vary over a fairly wide range to cover accelerated ageing and natural ageing. Beyond a certain degree of complexity, often exceeded in the context of oxidative ageing of polymers, the usual parlance is incapable of describing the interactions at stake and the multiple relations of cause-to-effect in play. Thus, a mathematical model is an irreplaceable tool, both for interpreting behaviors and for discussing the mechanisms. A model does not claim to be an exact representation of reality; it tries to get as close as possible to it, but its main purpose is to serve as the basis for discussion and a starting point for creating a better model, which, in time, will replace it. In that respect, an “open” model, i.e. extendable and modifiable depending on the hypotheses made, is preferable to a “closed”, unchangeable model.

1.2. Empirical and semi-empirical models

1.2.1. The Arrhenius model

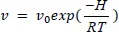

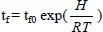

Since the 19th Century, we have had Arrhenius’ law at our disposal, which expresses the rate v of an elementary process as a function of the temperature:

where v0 (pre-exponential coefficient) and H (activation energy) are characteristic of the process. In the 1940s, the idea emerged that this law could be extended to complex processes such as ageing, in which numerous elementary processes are at work [DAK 48]. One of the hypotheses upon which this idea is founded is that, generally, the overall kinetics will be governed by an elementary process which “dictates” the rate of change. If the rate obeys Arrhenius’ law, then the lifetime tf must also obey this law:

This is therefore enough to determine the values of the lifetime at a number of different high temperatures, place them on the Arrhenius plot: Log tf = f(1/T), determine the best straight line by linear regression and extrapolate to the temperature of use Tu. There has been general consensus as regards this method for the past half-century. It has even been the subject of various international standards (Thermal endurance profile IEC 455-1-1974; IEC 483-1-1974; IEC 216-4-1980; AFNOR NF 26–205). However it is difficult, if not impossible, to verify the validity of the hypotheses made, except by determining the lifetime in natural ageing, which largely solves the problem. As we shall see later on, oxidation is in fact a process whose overall kinetics may deviate from Arrhenius’ law for various reasons [AUD 07]. This has been proven experimentally [CEL 05; GIL 05; GIL 05b]. Without going into detail for the moment, let us note that for a given material, practitioners use different parameters depending on whether the samples are thick or thin. Where does the boundary between the two lie? Is there no intermediate area? How does the boundary change when the temperature is decreased? Once again, we can only provide an empirical answer to these questions if we are able to determine the lifetime at the temperature of use on samples of different thicknesses, which renders any modeling useless.

NOTE.– The reasoning which leads us to reject the Arrhenian model remains valid for any law of time-temperature superimposition, e.g. the WLF law, or the unformulated law represented by a master curve.

1.2.2. The isodose model

Let us consider the case of ageing by irradiation (photo or radiochemical). It may be remarked that the literature on radiochemical ageing often gives tables of lethal doses, which only makes sense if we assume that the kinetics are independent of, or only slightly dependent on, the dose rate — in other words, that the end of life is an isodosic characteristic. As we shall see, the reality is entirely different. Certain authors have attempted to resolve the problem by seeking empirical laws, e.g. linking the lethal dose to the dose rate by power laws [WIL 87], but the limits of the validity of these laws are difficult to appreciate, and we shall see that in reality, the exponent of these laws diminishes constantly and tends towards zero as the dose rate decreases. In the case of photochemical ageing, the norms are ambiguous [VER 07], but in practice, we note that for a long time accelerated ageing systems were unable to vary the light intensity. This only makes sense if we assume, here as well, that the lifetime is an isodosic value, which again is far from true. The remark made about empirical power laws linkin...